Copy by R. Harris of painting destroyed in fire at Medical Building. Artist unknown.

By Gillian Woodford

From his dramatic beginnings in captivity in Spain following the capture of his family’s ship en route to Canada from Britain, Dr. Andrew Fernando Holmes would go on to co-found McGill’s Faculty of Medicine and become its first Dean.

Born in 1797, Dr. Holmes was a notable man of parts even by 19th century standards: a physician and medical innovator, a botanist and geologist, as well as a devout Christian and civic-minded Montrealer. In 1823, the Edinburgh-educated Dr. Holmes, along with his Montreal General Hospital colleagues Dr. William Robertson, Dr. John Stephenson and Dr. William Caldwell, founded the Montreal Medical Institution (MMI). It was the first medical school established in Canada and would later merge with McGill College and become its Faculty of Medicine in 1829. Dr. Holmes succeeded Dr. Robertson as head of the Faculty in 1843; in 1854 his title was changed to Dean, making Dr. Holmes the Faculty’s first Dean, a post he held until his death in 1860.

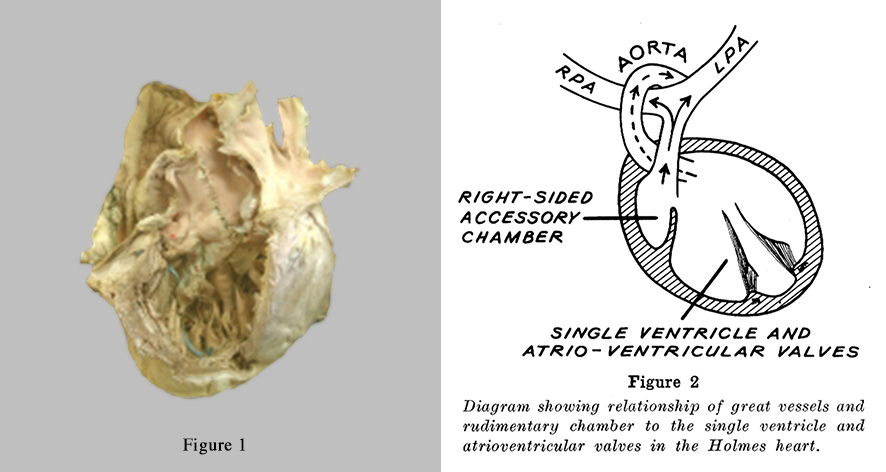

Dr. Holmes, who had a lifelong interest in disorders of the heart, has one named after him: the Holmes heart. In 1824, he presented an account of a rare defect discovered during the autopsy of a young man who was found to have a single ventricle, the first such documented case. In a strange twist, Dr. Maude Abbott came across the unclassified oddity three quarters of a century later, in her role as curator of McGill’s specimen museum. She asked Dr. William Osler to help her identify it. He remembered it as the one “old Dr. Holmes” had described. Dr. Abbott reexamined the heart and republished the findings in 1901, which in turn led to her contribution of the congenital heart disease chapter of Dr. Osler’s seminal System of Modern Medicine in 1905. The Holmes heart could be said to be the catalyst for both her fruitful collaboration with Dr. Osler and her distinguished career in cardiology.

The soft-spoken, meticulous Dr. Holmes was a dedicated innovator at McGill and at the Montreal General Hospital. He appears to have been an early adopter of the

stethoscope,not surprising given his interest in heart disorders, making the first known reference to its use at McGill in 1850, thirty years after its invention. “Like most other improvements,” he said in a valedictory address to graduating medical students that year, “it met with opposition at its first introduction; but this has now quite disappeared, and its only obstacle is that which shares with all other objects of pursuit, the labour necessary for acquiring expertness in its application. It has not only given precision to our diagnosis of diseases of the chest: it has led to the discovery of others not before suspected.”

Then, as now, scientific and medical knowledge was virtually exploding, and Dr. Holmes urged the newly minted doctors “to keep up with the constantly changing, and generally (if not always) improving aspect of the science.”

Some of Dr. Holmes’ most lasting contributions to Montreal and McGill have little to do with medicine at all. His large plant specimen collection, amassed early in his career

mostly on Mount Royal as well as other parts of the island of Montreal, was donated to McGill in 1856. It became the basis for the University’s Herbarium, now located at the Macdonald campus. He also dabbled in geology, and his mineral collection was purchased by the University and is a significant component of the Redpath Museum.

Dr. Holmes’ legacy in the Faculty of Medicine continues with the Holmes Gold Medal awarded to the medical graduate with the highest standing and the Holmes Lectures, a prestigious series of talks delivered by international experts in health care fields.

April 27, 2017