McGill researchers are working to ensure that the multiple promises of RNA medicine are shared equitably throughout society

Montreal’s Parc Extension is one of the most diverse communities in the city, with 61 per cent of its population made up of immigrants. It is also one of the poorest boroughs not only in the city, but in the entire country. When COVID-19 struck, these two factors contributed to vaccination rates which were consistently 10-15 per cent below the Montreal average.

McGill student Tammy Bui, herself the daughter of Vietnamese immigrants, resolved to turn this situation around. She conceived of a unique student project for the Foundations of Health Promotion course taught by Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health professor Ananya Banerjee.

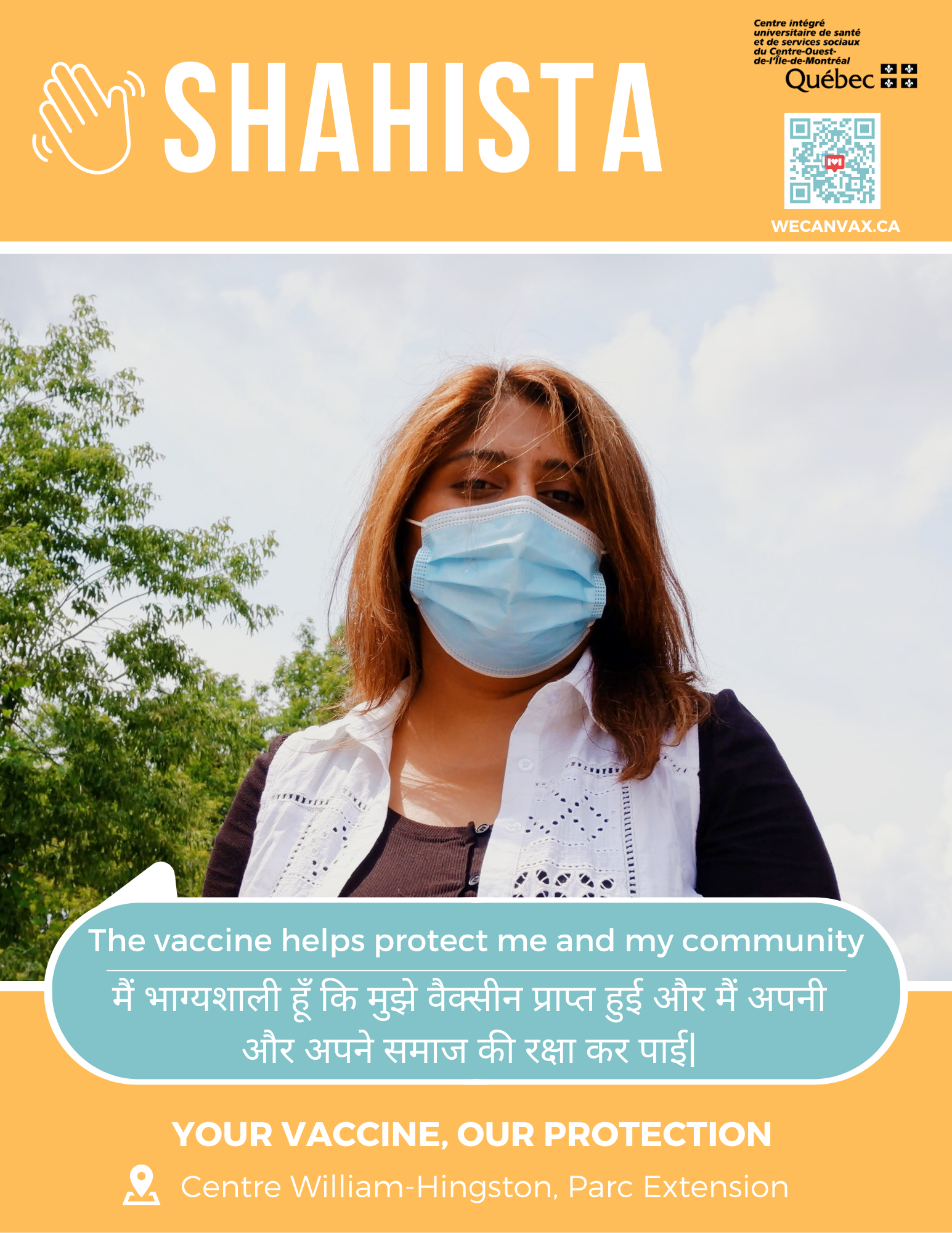

“Government-issued posters about the pandemic were often alienating to minority populations, either because of the language barrier or by nature of those materials lacking multicultural representation,” Bui told the McGill Reporter. So she and her student partners launched WeCanVax, an initiative aimed at confronting vaccine hesitancy.

They photographed community members, and used posters and social media to present testimonials from these individuals sharing why they had received the vaccine, in several languages. “It makes a huge difference to see yourself and your neighbours represented in messaging like this,” said Bui’s fellow student Nehal Islam. “Especially in a neighbourhood where so many languages are spoken, something as simple as creating posters in residents’ native languages sends the message that we see them and that their health is important to us.”

The student initiative boosted the borough’s vaccination rate to 79.5 per cent – several percentage points higher than the city average – a clear instance of how tailored, community-sensitive messaging makes a difference. Such an approach should also become part of the planning for the distribution of RNA-based medicines.

Realizing the promise of RNA

Therapies based on RNA research promise a health care revolution, with everything from effective and rapidly produced vaccines – witness the Moderna and Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines – to targeted gene therapies. But this promise will be fully realized only if these therapies are distributed equitably. And even in wealthy countries like Canada, with ostensibly universal health care, equitable access remains a concern.

People in positions of vulnerability – the racialized, the poor, the elderly and the disabled – are those likeliest to suffer heavily from viruses and many other diseases. “Disease, health and social factors are strongly intertwined. And we have known this at least since 1845, with the publication of Friedrich Engels’ writings on the conditions of workers in industrial England,” says Amélie Quesnel-Vallée, who is jointly appointed in the Faculties of Arts (Sociology) and Medicine (Epidemiology) and holds the Canada Research Chair in Policies and Health Inequalities. “Consideration of the needs of populations in positions of vulnerability can help us deliver better care.”

In Montreal and across Canada, the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates were found in some of the poorest neighbourhoods – like Park Ex – where people are often not in positions to take time off from work in order to be vaccinated, much less to receive boosters.

Community buy-in needs community involvement

“A first step in addressing systemic inequalities involves recruiting people from marginalized groups into the medical research profession, and initiatives at McGill are seeking to do this,” says Quesnel-Vallée. “We need people who are familiar with the cultural understanding of science of different communities, such as Indigenous communities, to help researchers understand how to engage with those communities in a culturally safe way.”

For RNA-based therapies, says Quesnel-Vallée, bringing in those people whose conditions are targeted by the research is also critical. “We want to make sure that those populations are able to say exactly what they want from research, as it could be that they identify some avenues that are different from those being pursued by university researchers. We need to listen with humility to the lived expertise that those people bring.”

Rare diseases represent a good example where new RNA-based therapies could have a huge impact. Quebec has populations with what are called “founder effects” due to small populations that have interbred and have increased risk of certain rare conditions. But because only a small population is impacted by them, profit-driven pharmaceutical companies are not focused on developing treatments.

“This is where the university’s impact is so important,” says Quesnel-Vallée. “Because we are publicly funded, we have a public duty to tackle some of those rare diseases. And we need to work with the patient populations to understand where their priorities lie.”

_______________________

RNA-based treatments have the potential to transform healthcare, making it more affordable and equitable. Discover how McGill experts are leading the RNA revolution.