1968

It was 1 pm on the first Monday in July 1968. This day marked the opening of the Pointe-Saint-Charles Community Health Centre (PSCC). Five second- and third-year medical students (Danny Frank, Margaret Ward, Stan Spivak, Frank Gougeon and Charles Larson) and a sociology student (Abe Rosenfeld), following six months of preparation and a $25,000 grant from the John and Mary Markel Foundation in hand, anxiously awaited the arrival of the clinic’s first patient.

Fifty-three years later, this clinic continues to be the primary provider of preventive and front-line curative health services for the majority of the neighbourhood’s French and English-speaking population.

50 cents per visit

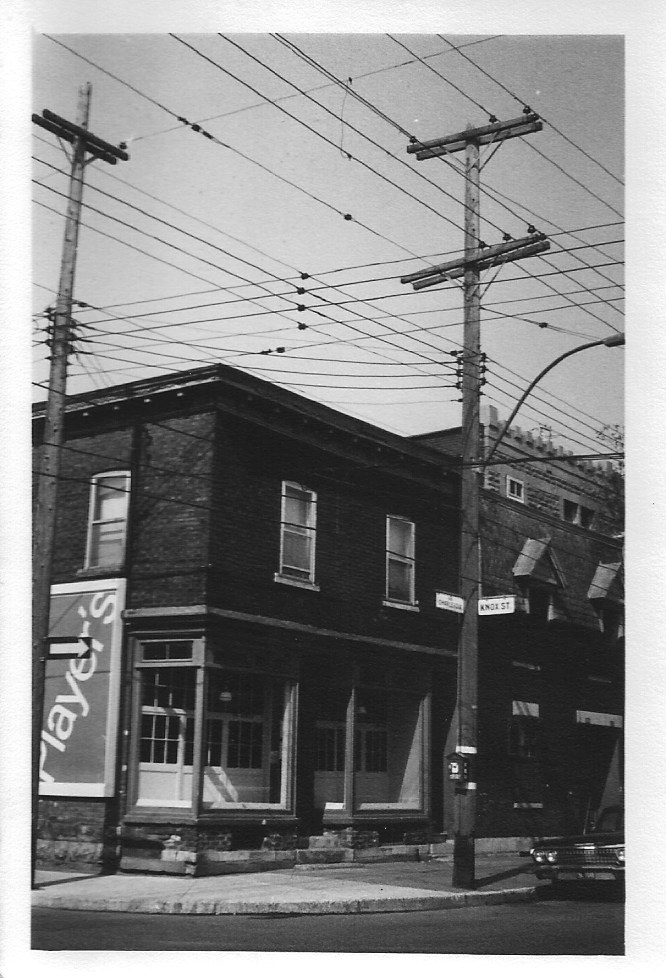

Located in the Montreal working class neighbourhood of Pointe-Saint-Charles (known as “the Point”), the clinic occupied a former butcher shop on the corner of Knox and Charlevoix. It had a large front window in which hung a sign reading:

Pointe-Saint-Charles Medical Clinic

Open 1 to 8 pm

50 cents per visit

(This was prior to the institution of Medicare in Quebec in 1971.)

At the time of the clinic’s opening the Point was a community suffering from decades of decline. Once the largest industrial complex in Canada, offering low paying but steady jobs to thousands of workers, the Great Depression marked the beginning of its decline. Most of the factories lining the Lachine Canal, marking the northern border of the Point and its industrial heart, were closed down. Eventually, even the canal itself was closed to commercial traffic. As a result, by the mid-1960s the Point was characterized by mass unemployment, exposure to over 100 years of industrial pollution, deterioration of the neighbourhood and deplorable housing conditions. Cut off from downtown Montreal by the deserted canal and a vast railway system, the population found itself isolated and neglected, with nearly non-existent health services, and only one family physician serving a population of 30,000 the time.

The mid-1960s also witnessed the beginning of student class community activism. This marked the end of a centuries-old hold of the church on the lives of most French, Italian and Irish Canadians and the emergence of community organizations intent upon reversing the pervasive neglect, nepotism and corruption that had characterized the Point for decades. It was in that context that the establishment of a primary care community health clinic was conceived by a small group of activist-minded medical students at McGill University, beginning in 1967.

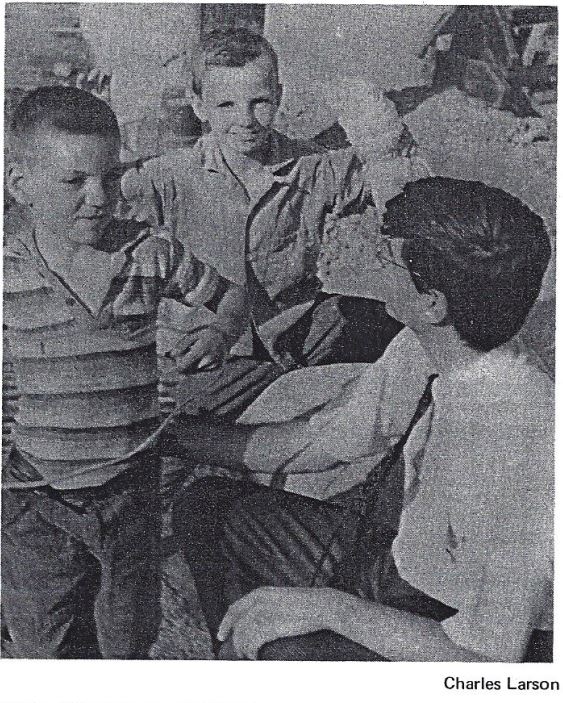

The idea of establishing a community clinic in the Point was inspired by the Student Health Organization (SHO) movement which had spread across several North American medical schools. This movement was driven by the enormous health disparities found in low-income communities and a reformist philosophy of improving the health of the disadvantaged via social change and community engagement. It was additionally influenced by the neglect of traditional medical training to include social determinants of health and exposure to real-life experiences outside teaching hospital settings. (For a history of medical student activism, see White Coat, Clenched Fist by Fitzhugh Mullan. This book and its ideas influenced the clinic’s medical student founder, Daniel Frank, who had participated in Martin Luther King’s civil rights activities while he was a high school student in Philadelphia. When Frank left the project to finish his medical studies, the student leadership was taken over by Charles Larson who strengthened the ties between the clinic and local citizens and was instrumental in forging the neighbourhood “ownership” of the clinic.)

Neighbourhood first

From the outset, the clinic’s student founders intended that all decisions would be made from a “neighbourhood first” orientation. It would be a community clinic grounded in local engagement and eventual control, inspired by the civil rights movements of the day and the organization of low-income, disenfranchised populations to actively defend their interests.

A meeting in a local grade school with parents was arranged in the spring of 1968. The aims of this meeting were to present the idea of a local primary care health clinic, obtain their response, and to open up a broader discussion of what they considered to be priority – unmet health or social needs in the community. While generally supportive of the idea of a clinic, being the parents of young children, it was not surprising to learn they had other, equally important, concerns to be addressed. Top on their list was the absence of any organized summer activities for their children. This led to the decision to begin the planning of a summer program titled the “Alleyway Summer Camp,” with the full engagement of the parents. These same parents eventually became the window into the community who guided the early implementation of a clinic.

Faculty support

Early on, the students sought the advice and support of several McGill medical faculty. Important early supporters were Drs Elizabeth Hillman and Nick Steinmetz from the Montreal Children’s Hospital. They helped with the grant application and, most essential, identified additional faculty who volunteered as medical supervisors and mentors during clinic operating hours. The original $25,000 grant was deposited in a Faculty of Medicine account with the support of Dr. Maurice McGregor, then the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. With these funds the storefront location was rented and a full-time nurse, Barbara Stewart, hired. Specific evenings were set aside for pediatrics, internal medicine, and OB/GYN. Much-needed supplies were provided by the visiting physician mentors who volunteered their time over the coming nine months on a weekly basis. Early in 1969, a community organizer, Peter Katadotis, was hired on a part-time basis and worked with a McGill social work graduate student, Betty-Ann Affleck (supervised by Sheila Goldbloom). Along with Barbara, they provided social services during the day. In addition to Charles Larson, some of the medical students who subsequently became involved in 1969 were Roger Stronnell, Collis Wilson, Robert Robson, Robert Remis and Elizabeth Robinson.

The ability to eventually hire a full-time physician was made possible in 1969 through a grant from the Department of National Health and Welfare of Canada. Dr. Francois Lehman, a McGill graduate, was hired and remained at the clinic for the next decade. In 1970, The McConnell Foundation donated $20,000. The Minister of Health, John Monroe, visited the clinic that summer and awarded a second grant for $75,000 for the 1970-71 financial year. With these funds in place the clinic now had a full-time nurse and physician. In the fall of 1970, the governance of the clinic was formally transferred from the McGill Student Health Organization to a community-led board of directors.

Community-led, then and now

The original goal of the project was to create a community health centre staffed by volunteer students and medical faculty mentors, but to eventually hire salaried physicians, nurses and community organizers. From the beginning, it was also the aim to turn the clinic over to the community overseen by an elected board of directors. By 1970, this proved ultimately successful and became a precursor to Quebec’s eventual network of local community social service centres (Centres locaux de services communautaires, or CLSCs). In spite of repeated demands over the ensuing decade from the Ministry of Health and Social Services for the clinic to be governed under the government’s CLSC system of health care, these attempts were successfully rejected in alignment with the strong commitment toward local, community control, that exists to this day.

At a 50th anniversary gala attended by over 2000 supporters held in the Point, the founding role of McGill medical students was honoured as a testimony to the impact student activism can have. After all these years their appreciation and recognition remain alive and an inspiration for those who have followed.

Related:

The student founders of the clinic produced a publication called Contact, which documented the establishment and progress of the clinic and other community initiatives, and also contained photos, drawings and poetry. Read the first three issues here (PDF):

Return to Stories from our Faculty community

Return to 200 Years, 200 Stories