On September 26, Heads of State will gather in New York at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly’s first-ever high-level meeting on tuberculosis (TB) to accelerate efforts to end TB and reach all affected people with prevention and care.

As a lead-up to the UN meeting, India has announced its own ambitious plans to eliminate TB by 2025. With the world’s largest TB burden and rising multidrug resistance, this will be a daunting task, particularly with private sector health care providers serving as the first point of contact for 50-70% of patients with TB symptoms in India. “The Indian government is working hard to engage the private health sector, but little is known about the quality of care they provide,” said Dr. Madhukar Pai, who is the Director of the McGill International TB Centre, a Professor of Epidemiology at McGill University and a Scientist at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre.

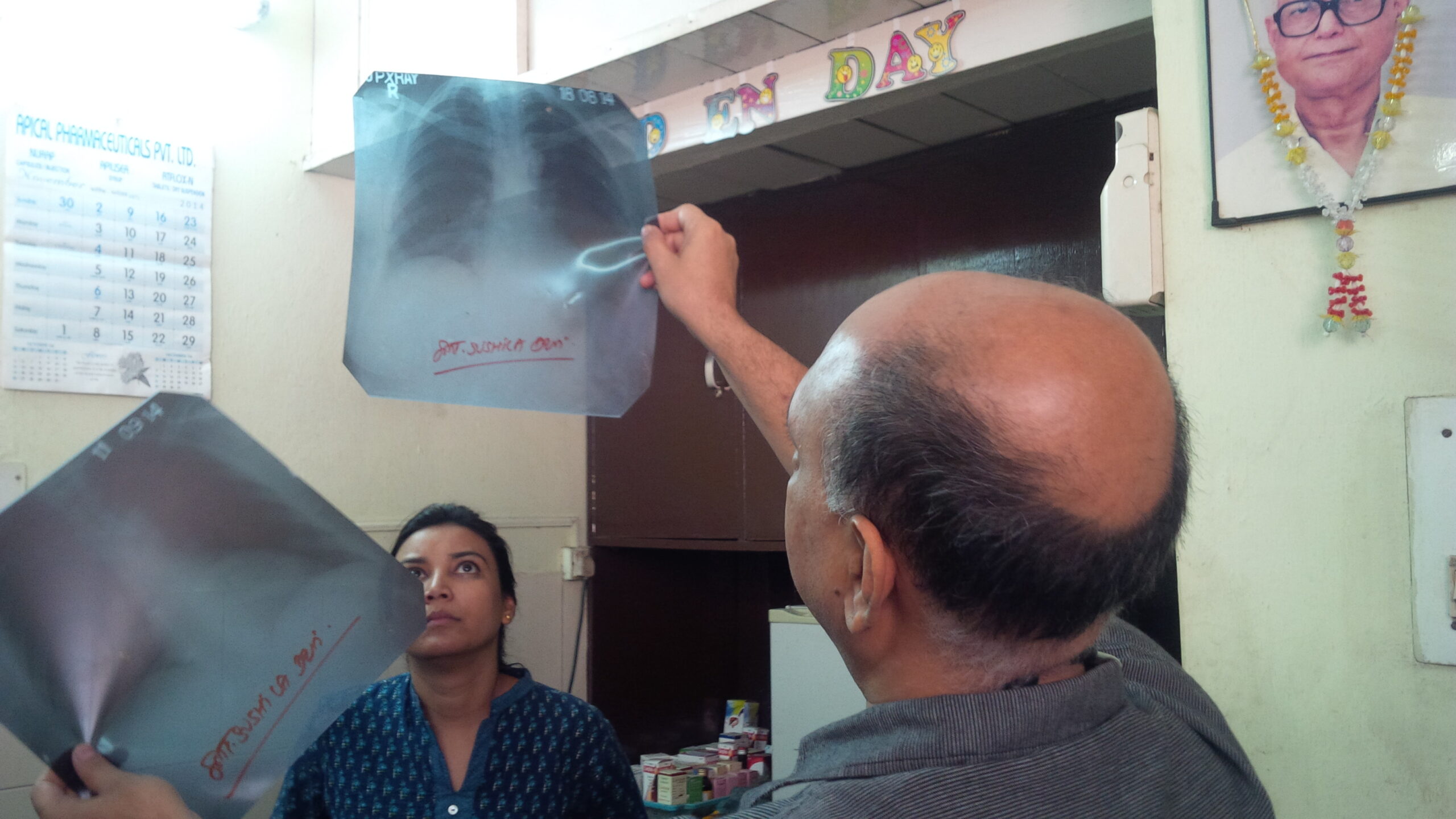

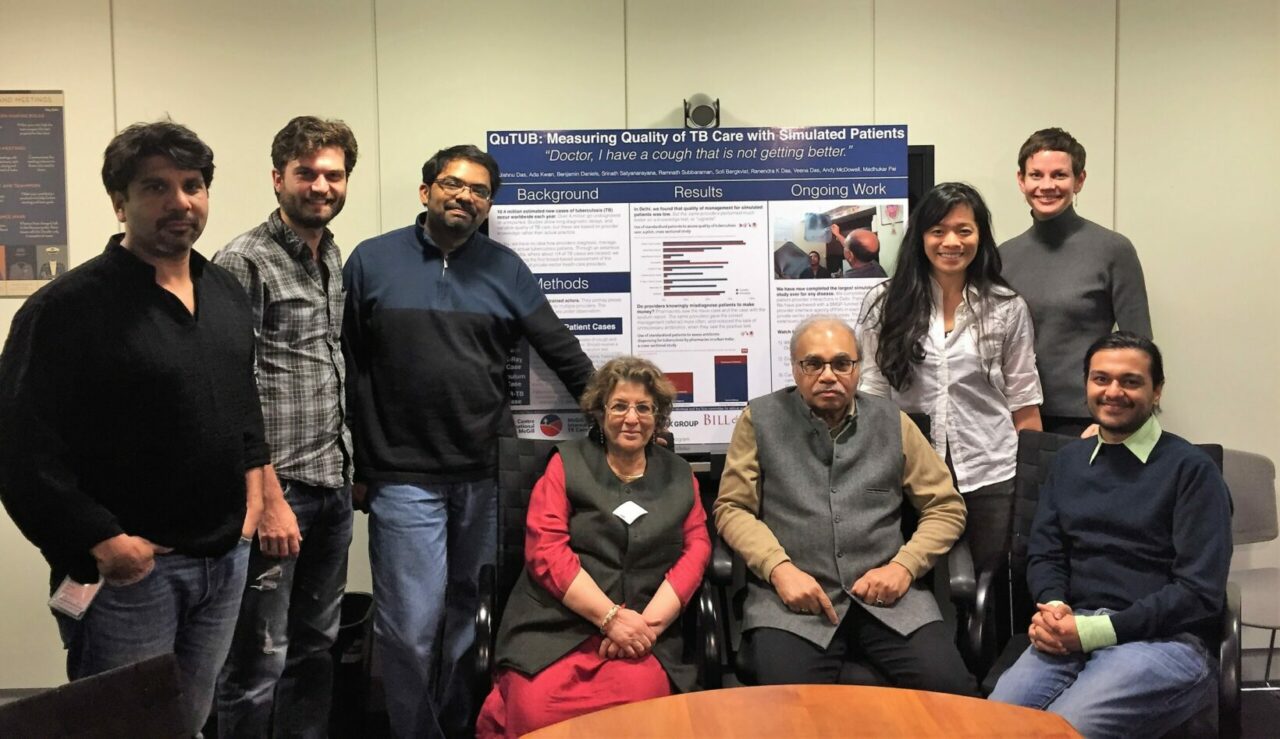

According to a study published this week in PLOS Medicine, private practitioners are delivering a wide range of largely inadequate care to these patients. Dr. Pai, working with Ada Kwan, a PhD student at the University of California at Berkeley, Benjamin Daniels and Dr. Jishnu Das from the World Bank, and other colleagues, utilized 24 standardized patients (SPs) – seemingly healthy actors trained to portray four different tuberculosis case scenarios during unannounced visits – to assess management and quality outcomes of private providers stratified by qualification in Patna and Mumbai, India.

A total of 2,652 SP-provider interactions were analyzed across 473 Patna providers and 730 Mumbai providers and weighted for city-representative interpretation. Providers correctly managed SP cases according to national and international standards in only 949 interactions (35% after weighting; 95% CI 32%–37%). Providers often stuck to the same erroneous protocols with other SPs, repeating their own observed actions 75% of the time in a second visit by a different patient. However, there was not a single widely adopted “common practice” among providers: SPs encountered a wide range of observed quality and various treatment protocols within each provider qualification stratum.

Nevertheless, there were several positive findings. First, allopathic providers with Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) degrees or higher were far more likely to correctly manage cases than non-MBBS providers (odds ratio 2.80; 95% CI 2.05–3.82; p < 0.0001). Second, there was near-zero use of anti-TB drugs among non-MBBS providers. In general, these drugs were judiciously used with the correct regimen and dosage in all but five of 118 cases. Finally, providers who were presented with more diagnostic information by the patient offered better care, even if it meant referring their patients to the public sector TB program.

Kwan and Pai believe that as India seeks to eliminate TB there are clear challenges but also tremendous opportunities: “Rather than a simple message of “good” or “bad” care in the private sector, our study shows that a number of qualified physicians provide excellent care, while we also found providers who consistently mismanaged patients. Engaging quality providers, ensuring a referral chain that leads patients to these providers, and linking their patients to free TB drugs and other subsidies in the public sector could be a useful strategy for India.”

The authors note that SPs cannot account for the broader mix of patients a provider sees nor can they assess how a provider might manage a patient in subsequent visits. Neither is data from the public sector available that this care can be compared to. Nevertheless, these results indicate that improving TB management among urban India’s private health sector should be a priority for India’s TB elimination strategy.

Funding:

This study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Canada, and the Knowledge for Change Program at the World Bank.

Madhukar Pai

Jishnu Das

or

Jason Clement

Communications Officer, Faculty of Medicine

McGill University

514-398-5909

The Hindu | Private clinics off mark in TB care

Forbes | News From The UN’s High-Level Meeting On Tuberculosis

The Telegraph, India | 70% TB patients might not get right care: study

Libération | En Inde, contre la tuberculose, de nombreux docteurs ne sont pas au niveau

Infectious Diseases Hub | Tuberculosis care: variation and deficits uncovered in urban India

The Times of India | Private doctors fail to treat 60% of TB cases in Mumbai: Study

The Hindu Business Line | TB care in private sector found wanting: Study

The Indian Express | Vast variation, significant deficits in TB care in urban India: Study

Yahoo News | Many doctors in India miss TB signs: study

La Croix | En Inde, contre la tuberculose, de nombreux docteurs ne sont pas au niveau

Nature Microbiology | We cannot End TB by focusing on just coverage: quality also matters!

Indian Express | ‘Doctors share blame for pain of TB patients’

Firstpost | Better private healthcare in India crucial to eliminating Tuberculosis by 2025

Indian Express | More Potent Healers

September 25, 2018