Dr. Irving Fox (BSc’65, MDCM’67) speaks about his recent memoir, in which he investigates a mysterious illness he suffered as a medical resident, and discusses his planned gift to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Could you tell us about the flashing light you describe in your book?

It came out of the blue. The first time, I was sitting in my friend’s car and, although it was frightening, it soon disappeared and I forgot about it. It came back a few weeks later with other serious consequences: I lost sight on the left side of my visual field. In medical school, I had learned about a doctor who experienced flashing lights and a loss of vision—it’s called “homonymous hemianopsia”—and who had a brain tumour. I thought, “That’s me!” I was sure I had a brain tumour. I spent time at the Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital (MNI) and two months at the Allan Memorial Institute (AMI), where I was treated by some of my medical school professors. I had a lot of confidence in them, especially Dr. Francis McNaughton, who was the chief of neurology at the MNI. The psychiatrists who took care of me at the AMI were also notable professors. I don’t remember anything about the last two months, partly due to the large doses of medication I was receiving that affected my memory. When I accessed my medical records, I was astonished to discover my behaviours during that time. It was like reading about another person. Looking back, it’s amazing that I recovered.

After this episode, you had a brilliant career in academic medicine and later in the pharmaceutical industry, working towards significantly improving thousands of lives. How much of your career path was shaped by surviving this mysterious illness?

In retrospect, I was trying to give back to society for getting my life back. That’s one of the reasons I left academic medicine and went into the biopharmaceutical industry: I wanted to be closer to finding important drugs that would help people. It was a more tangible way of giving back, but I only realized that when I wrote the book.

What was it like moving from practising and teaching medicine to developing therapies?

It was a very unusual move at the time, and a high risk one, too. I was a tenured professor, we had a good place to live, and I moved to the Boston area to work at a biotech company where your tenure is based upon your performance. It took some time to adjust, to learn how to work in the industry, to learn about drug development, but I thrived, and we were successful. I worked with talented teams and was able to get some very important drugs approved during my career. One of them was Avonex, a treatment for multiple sclerosis; the other was Entyvio, used in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Both were significant breakthroughs and became blockbusters, garnering over $1 billion USD in sales.

How did the idea of writing the book come about?

When I retired, I decided to spend my time enriching my life by learning other disciplines. By writing this book, I realized the impact of my illness on my life. I thought I was a goner. When I got better, I felt as if I’d been given my life back and I was grateful. I dedicate the book to people who have a calamity in their lives because I want to give others hope that they, too, can get better.

You and your wife Gloria (BA’66) have created the Irving and Gloria Fox Research Bursaries for Medical Students, a planned gift in support of med students who want to take part in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences’ Summer Research Bursary Program. Could you tell us more about how your donation came about?

McGill is where my wife and I studied, where my illness and recovery took place, and from where I launched my career from. I feel grateful for what I received. When I attended medical school, a scholarship sustained me through the seven years of my education. And my career as a medical researcher was kickstarted by doing two summers of research at McGill. I did well in medical research, including drug development, and I thought, “What better way to give back than to support bursaries to benefit medical students?” I love research. I pursued a career in research and was always focused on it, even while in the industry. Drug development is very scientific and, although I gave up my lab, I didn’t give up my scientific thinking which I used to get drugs approved. I always encouraged my students to become interested in research. I tried to nurture it when doing clinical teaching by bringing up scientific aspects of a patient’s issues, going back to the physiology and pathology of their diseases, and describing drug posology. I hope the bursaries can instill that kind of thinking in some of the students.

You have also gifted your Holmes Gold Medal for being first in your class at graduation and your Walter Chipman Gold Medal for being first in your class in Obstetrics and Gynecology at graduation for exhibit in the Maude Abbott Medical Museum. Could you tell us about your gift to the Museum?

I never did anything with my gold medals. When I visited the Maude Abbott Medical Museum at my recent reunion, I saw the displays and contacted Dr. Richard Fraser, the head of the Museum. He was interested in displaying them, especially the Holmes medal. The Walter Chipman isn’t given anymore, so it’s of historical interest. I was delighted that they accepted them and I’m very pleased that those medals have found a home. Next time I visit McGill, I’ll go to see them on display in the Museum.

What advice would you like to share with actual and prospective students, and with young alumni, as McGill heads into its third century?

Make sure you change with the times. Pursue careers of excellence. Always be a philanthropic to society. Give what you can to help other people, whether it’s financially or mentoring during your career.

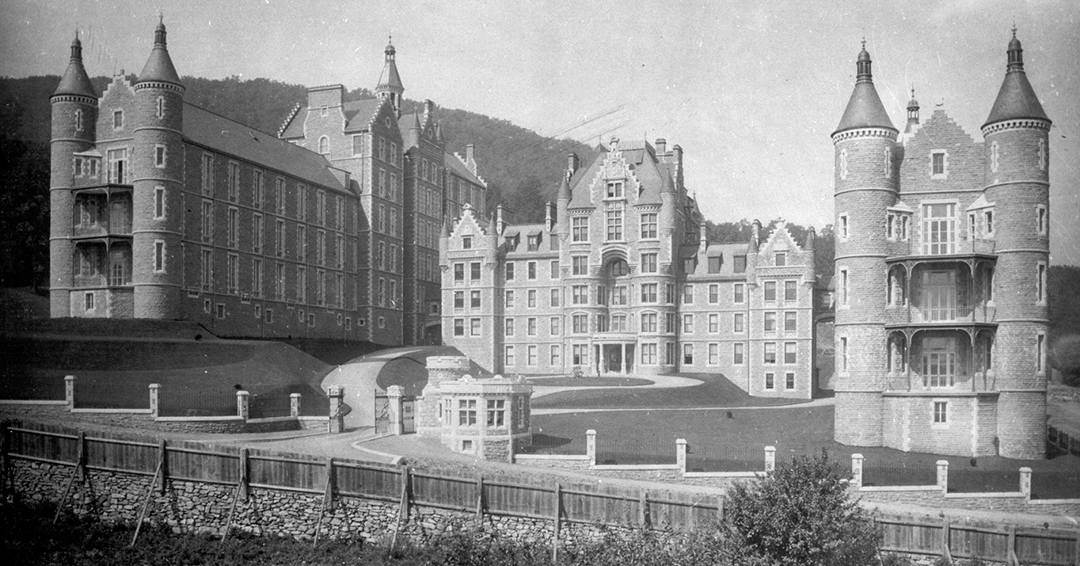

Pictured, top: The Royal Victoria Hospital (c. 1900), McGill University Archives, PR023637.