Discovery yields potential to block metastatic cancer

Metastatic breast cancer, whereby the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, is the most deadly aspect of breast cancer, causing the majority of deaths. While much is known about primary breast cancers, how breast tumours change and become metastatic is still not well understood.

Metastatic breast cancer, whereby the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, is the most deadly aspect of breast cancer, causing the majority of deaths. While much is known about primary breast cancers, how breast tumours change and become metastatic is still not well understood.

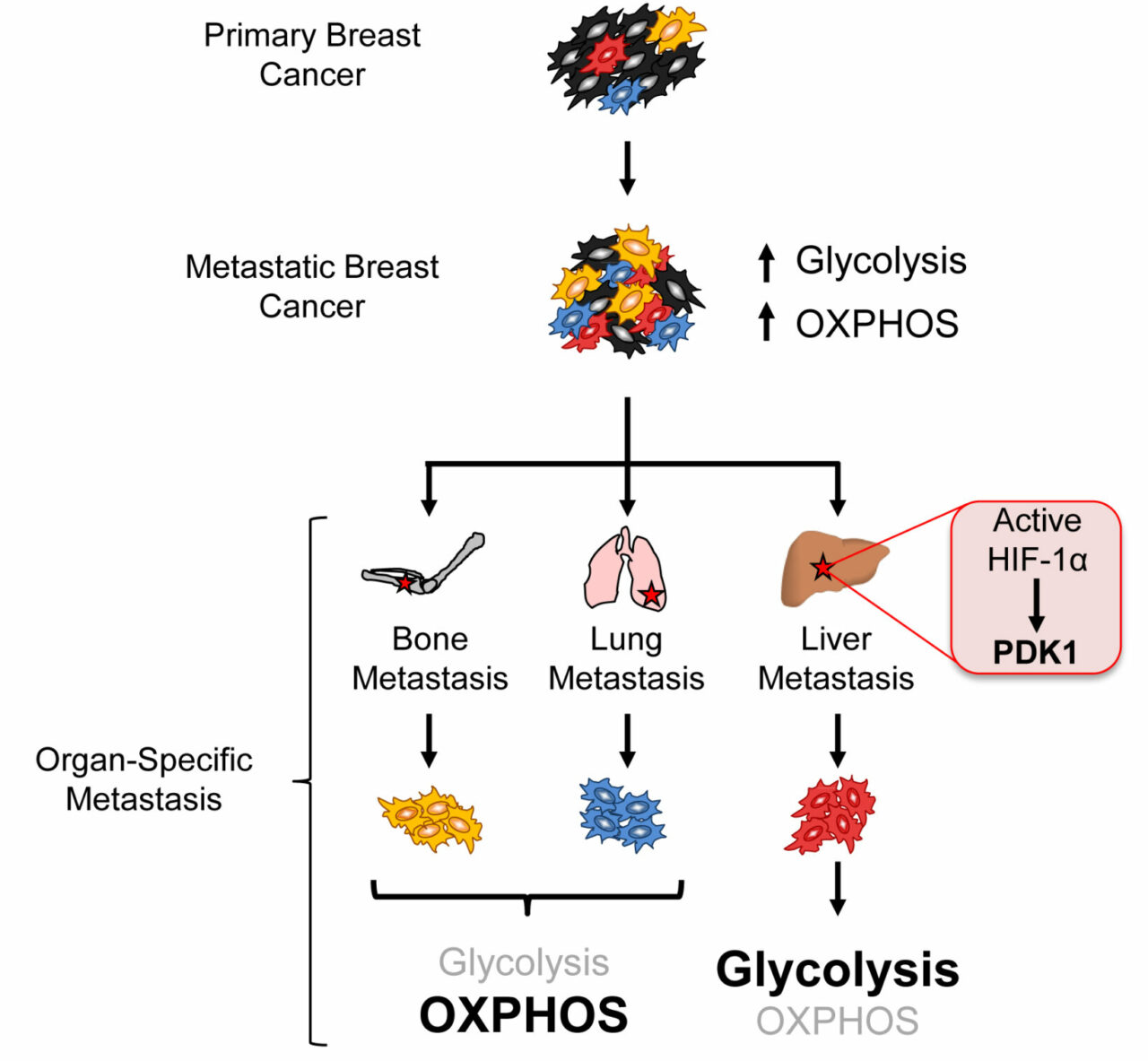

In order for a breast cancer cell to become metastatic in needs to be able to survive and grow outside of its primary environment. Up to now, little has been known about how metastatic cancer cells fuel themselves. In a new paper published in the journal Cell Metabolism, researchers in two laboratories at the Goodman Cancer Research Centre (GCRC), housed within McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine, show that metastatic breast cancer cells fuel themselves in very different ways depending on which site the metastatic cancer grows. The research was conducted by Fanny Dupuy, a graduate student co-supervised by Dr. Russell Jones, an Associate Professor in the Department of Physiology and Dr. Peter Siegel, an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine.

“For our work, we looked at how breast cancer cells adapt to grow in different sites like the bone, lung and liver,” says Dr. Russell Jones, one of the corresponding authors on the paper. “The main finding of our work is that we discovered that as breast cancer cells metastasize, they eat different things to help them grow and survive. What we found is that a specific gene that regulates sugar metabolism – known as PDK1 – helps breast cancer cells grow under stressful environments, and is essential for breast cancer cells to metastasize to the liver. We also found that PDK1 is highly expressed in liver metastases from breast cancer patients, meaning that this adaptation likely plays a key role in the human disease.”

By profiling the small molecule metabolites from cancer tissues, a process known as metabolomics, the researchers were able to identify metabolic vulnerabilities in metastatic  cells and then use these to target cancer cells. They discovered that when they blocked PDK1 expression in liver metastatic breast cancers-the ones that colonize the liver the best- their ability to cause disease was drastically reduced. The work was accomplished using the Metabolomics Core Facility at the GCRC, a specialized research facility that uses advanced chemistry techniques to profile metabolic changes in cancer.

cells and then use these to target cancer cells. They discovered that when they blocked PDK1 expression in liver metastatic breast cancers-the ones that colonize the liver the best- their ability to cause disease was drastically reduced. The work was accomplished using the Metabolomics Core Facility at the GCRC, a specialized research facility that uses advanced chemistry techniques to profile metabolic changes in cancer.

“Our results are important because they illustrate that cancer cells modulate their metabolism during the metastatic process, and that interactions between tumor cells and the tissues to which they spread has a large influence on how cancer cells generate cellular energy” notes Dr. Siegel.

Dr. Jones adds that, “this discovery is also important because it shows that we may be able to predict the behaviour of metastatic cancer cells by understanding how they fuel their growth. In the case of liver metastatic cells, we can block metastatic cancer growth by blocking the enzyme (PDK1) that regulates sugar use by tumour cells. This approach has the potential to open new doors for all cancer patients, not just ones with breast cancer, as it will help us to design new therapies to treat the most aggressive cancers.”

This work was a joint effort that included other members of the Oncometabolism Research team at the GCRC and collaborators from the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre and the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research located in Montreal. Collaborators from the Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre, the University of Toronto and the University of British Columbia also contributed to the research.