It is with great sadness that we announce our dear friend, colleague and mentor, Charles Scriver, MDCM, Alva Professor Emeritus of Human Genetics in McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, died in Montreal on April 7, 2023, at the age of 92. Our deepest condolences go out to Charles’ loved ones, particularly his wife Zipper, children Do-Ellen, Peter, Julie and Paul, as well as to his grandchildren and great grandchild.

A pioneer in the burgeoning field of medical genetics, Charles’ research focused on a subset of rare genetic disorders called inborn errors of metabolism. He became the leading expert in the subject, identifying many previously unknown disorders and spearheading Quebec’s innovative newborn screening program for congenital diseases, which has been replicated internationally. His work improved the lives of countless children and their families around the world. He was a beloved teacher and physician, who will be greatly missed by all who knew him, here at McGill and across Quebec, Canada and beyond.

Early life

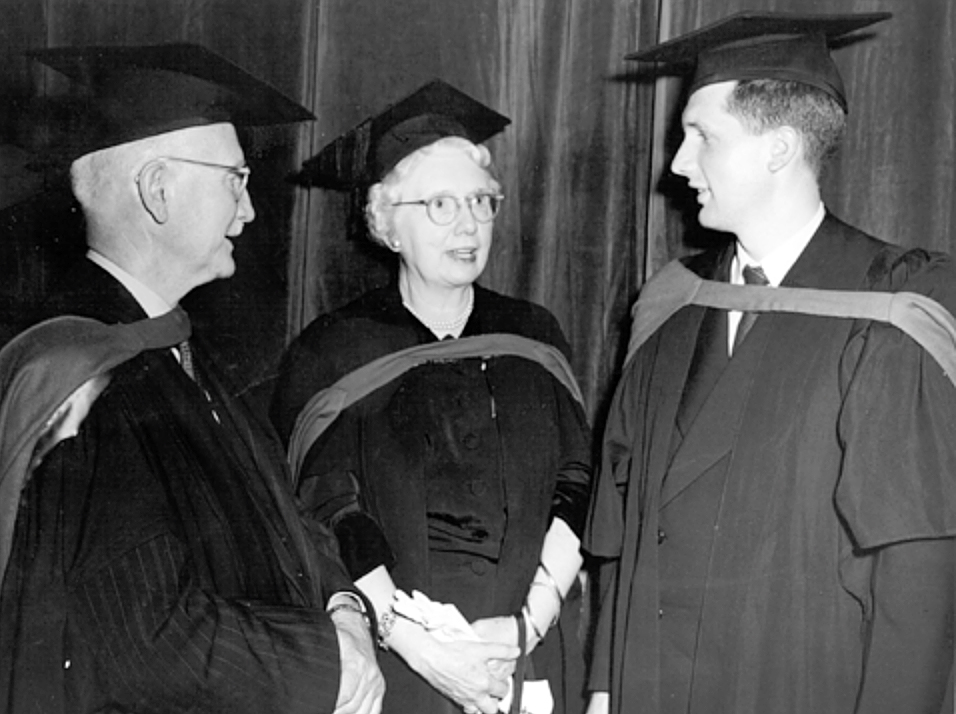

Charles Robert Scriver was born in 1930 in Montreal to a pair of McGill-trained physicians, Jessie Boyd Scriver and Walter Scriver. Dr. Jessie, as she was known, had been part of the first medical school cohort at McGill to accept women students – a right she had fought hard to obtain. She became Montreal’s first woman pediatrician, the Royal Victoria Hospital’s first woman Chief of Pediatrics and the first woman president of the Canadian Paediatrics Society. Walter Scriver was an internist who specialized in diabetes and renal diseases and was Physician-in-Chief of the Royal Vic.

After pursuing an undergraduate degree in geography and literature, Charles followed in his parents’ footsteps, studying medicine at McGill and graduating in 1955. Like his mother, he chose pediatrics, but later specialized in pediatric genetic disorders. Charles later said his mother’s important early work on sickle cell anemia inspired his interest in this area.

Growing interest in genetics

Charles and his new wife Zipper moved to Boston – she to nurse and he to complete his pediatrics training at Harvard. It was here that he gained exposure to the possibilities of research into metabolic disorders through two of his young patients. He learned about an intriguing new tool called chromatography and accepted an opportunity to work in the lab of Charles Dent, the leader in this technique, at University College, London. While there, he discovered both a new inborn error of metabolism called hyperprolinemia, as well as a novel renal transport system. His findings were published in Nature and New England Journal of Medicine.

Charles and Zipper decided to head back to Montreal with their young family. Fulfilling the demanding role of Chief Resident for pediatrics, Charles’ mentors nevertheless protected his time and gave him lab space to continue his line of research, allowing him to introduce the new techniques he had learned in the Dent lab to North America. He became a faculty member of the McGill medical faculty in 1960. He told Health e-News in a 2017 interview, “When I started at McGill, the general understanding was that genetic diseases are like stamp collecting. They’re odd things so why bother about them because you can’t do anything about them.” Undeterred, he soon helped found the DeBelle Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, which became the international leader in inborn error of metabolism research.

Community genetics

In the late 1960s, Charles became well known in Quebec for championing the addition of vitamin D to milk to reduce cases of rickets. He and his DeBelle colleague Carol Clow had observed an increase in cases in his less affluent young patients during the winter months and upon investigation learned they were being fed cow’s milk and not baby formula like wealthier families. He managed to convince the milk board to make the change, but it was not until he enlisted the help of Arnold Steinberg of Steinberg’s grocery chain that he was able to get the fortified milk on shelves in Montreal. Mr. Steinberg famously threatened to pull milk from his stores’ shelves if it didn’t contain vitamin D (“No vitamin D, no contract,” he told them). The reduction in cases of vitamin D-related rickets allowed Charles and his team to identify an inborn form of rickets previously unknown.

Charles and Carol Clow developed a blood test to detect a variety of inborn errors of amino acid metabolism. This led to the creation by Charles and others of the Quebec Network of Genetic Medicine, a pioneering screening program to test newborns for congenital disorders, in 1969. This program became a model around the world and has helped countless babies receive timely treatment for a variety of disorders as well as advance research into causes and prevention.

This led to a second, lesser-known collaboration with Arnold Steinberg. Babies born with metabolic disorders often need to follow highly specialized diets in order to thrive. Unfortunately, the specially prepared food was hard to come by in Canada. Charles once again called on Mr. Steinberg for help. The pair created the National Food Distribution Centre (better known as the Food Bank), a centralized distribution centre based in Montreal that supplies the products to this day to patients across Canada.

Charles was also a leader in population genetics. As co-director of the Société interuniversitaire de recherche sur les populations (SOREP; then IREP, Institut interuniversitaire de recherches sur les populations), a consortium of McGill, Laval and Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, he and others created a large database to track and study genetic disorders in Quebec’s population, leading to earlier detection and treatment. Charles was also involved in the creation, in 1972, of the McGill Group in Medical Genetics, with Clarke Fraser, MDCM, who had established the Division of Medical Genetics at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. The Group united genetics researchers under one umbrella and made McGill a leader in medical genetics research in Canada. He was instrumental to the development of the Human Genome Project – his early recognition of the importance of gene mapping led him to champion and facilitate its creation in the 1980s.

Charles referred to his work – a mixture of clinical care, research and advocacy – as “community genetics” because he saw it as his duty to society to improve the lives of children and their families. Through his training in chromatographic techniques, over the course of his career, Charles and his teams of researchers and students identified more than 20 inborn errors of metabolism. Perhaps the most significant was his work on phenylketonuria (known as PKU), which when detected early can be treated to prevent severe intellectual disability.

A caring legacy

A tireless teacher and mentor, Charles is fondly remembered and revered by those who had the honour of working and learning with him. He and Zipper famously welcomed the DeBelle “family” to be part of their own family, hosting countless events and informal genetics debates at their home in Montreal West. His legacy, which lives on through his trainees, his research and his advocacy, is immeasurable.

“Charles Scriver was truly a giant in the field of medical genetics and an icon here at McGill and around the world,” says David Eidelman, MDCM, Vice-Principal (Health Affairs) and Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. “His commitment to solving pressing medical issues of the day through both scientific investigation and political action make him a model all health professionals should aspire to emulate. His influence on our Faculty is far reaching, and he will be greatly missed by those of us who knew and admired him.”

Generations of trainees and colleagues who worked with Charles Scriver have been sharing memories and tributes, including David Rosenblatt, MDCM, Professor and former Chair of the Department of Human Genetics, who was mentored by Dr. Scriver and was a Principal Investigator in the McGill Group in Medical Genetics. “Dr. Scriver had an immense influence across the world on an entire generation of clinicians and scientists in the areas of inherited metabolic diseases and human genetics. His work ethic was legendary. He assembled a culturally diverse group of colleagues in a time when it was not common and he always attributed his successes to the contribution of the entire team,” says Dr. Rosenblatt. “In everything he did, he brought honour and respect to himself, to Quebec, to Canada and to McGill, to which he was immensely loyal. He prided himself on the fact that his entire academic career was spent at McGill.”

Eric Shoubridge, PhD, Chair of the Department of Human Genetics, likewise remembers Charles as a great leader, teacher and scientist. “Dr. Scriver was responsible for catapulting McGill onto the international stage in the field of metabolic disease. His passion for genetics was truly infectious; he led by example and was the inspiration for many basic scientists who subsequently devoted their careers to the study of rare disease,” he recalls. “I was part of the McGill Medical Genetics group for several years and I think all of us who enjoyed that privilege owe a huge debt to Dr. Scriver for his visionary leadership and for fostering a truly collaborative genetics community at McGill, and indeed across the country.”

Charles Scriver was the recipient of countless honours during his lifetime. He was made a Companion of the Order of Canada (its highest rank), a grand officier de l’Ordre du Québec and a Commander of the Ordre de Montréal; he was the recipient of the Distinguished Scientist Award of the Medical Research Council of Canada, as well as the McLaughlin and Rutherford Medals of the Royal Society of Canada; he was awarded four honorary doctorates, by McGill and the Universities of Manitoba, Glasgow and Montreal; and last but not least, he was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.

Celebration of life information

A life celebration for Charles was held on Thursday, April 20th at the Loyola Chapel, 7141 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal H4B 1R6. Those who were not able to attend may view the recording of the ceremony here.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Scriver Family Prize in Genetics at McGill or the Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Genetics.

- Charles Scriver’s McGill medical school graduation photo (Old McGill 1955)

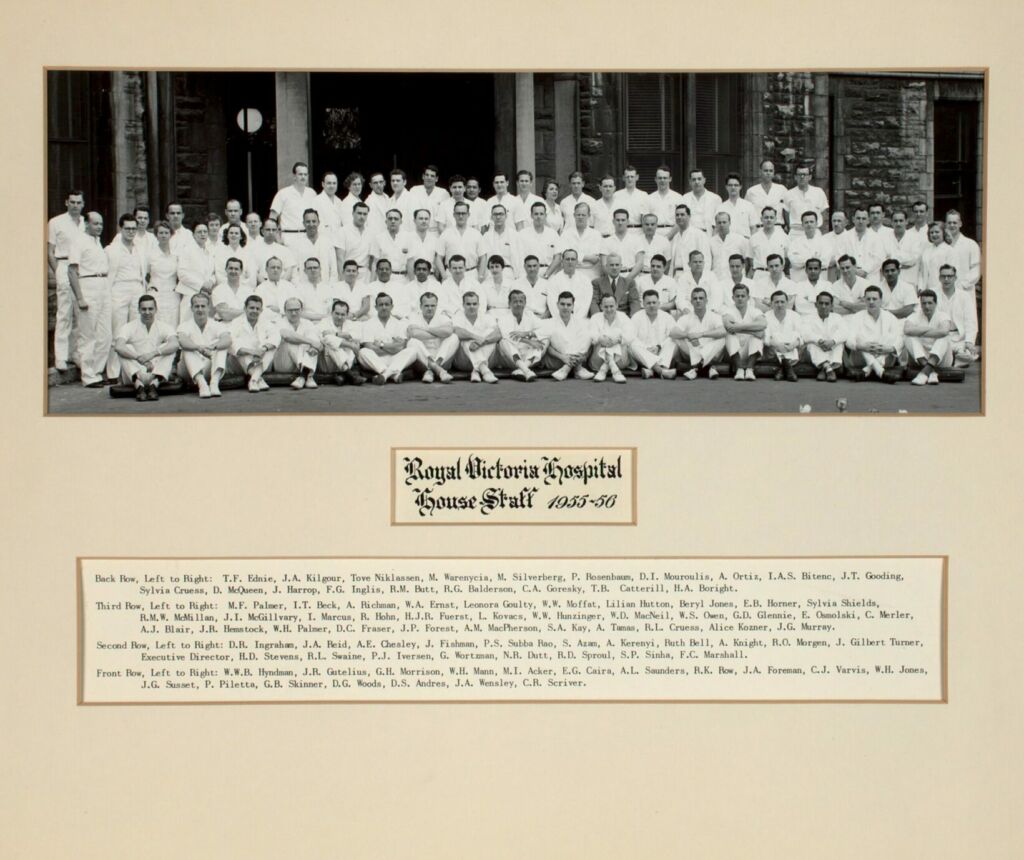

- Royal Victoria Hospital House Staff 1955-56: Dr. Charles Scriver is in the front row at the far right (Drs Sylvia and Richard Cruess were also in this cohort). (Photo courtesy McGill University Archives Photo Collection, PL006584. Photographer not listed.)

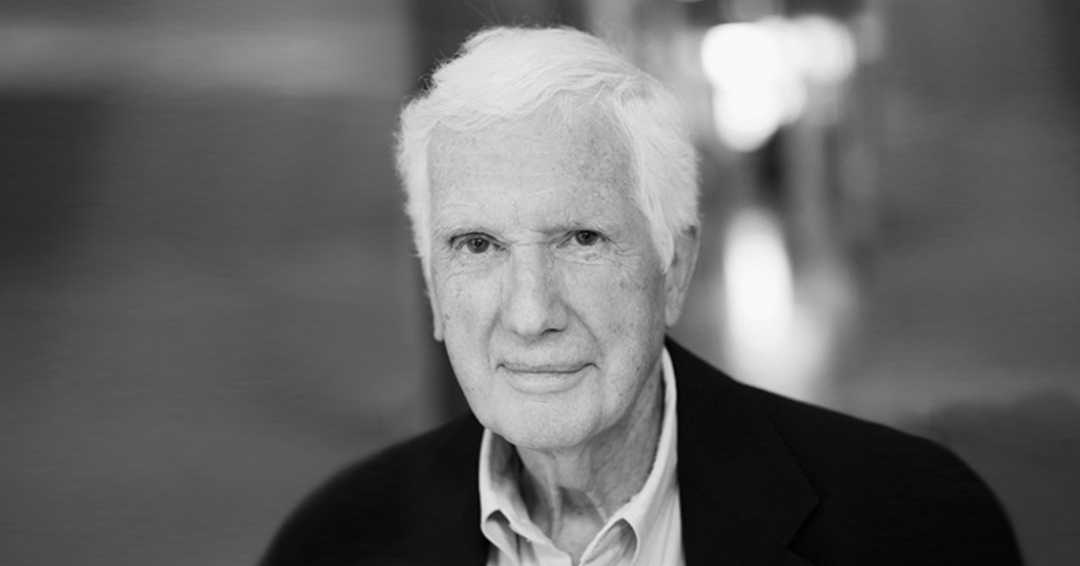

- Canadian Medical Hall of Fame portrait of Dr. Scriver (courtesy CMHF)

- Charles R. Scriver (courtesy the Scriver family)

Related:

Obituary: Remembering Charles Scriver

RI-MUHC: In Memoriam: Charles Robert Scriver, MDCM (version française)

Charles Scriver: Epitome of the physician scientist (Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, Volume 137, Issue 4, December 2022, Pages 388-398)

Canadian Medical Hall of Fame Laureate: Charles Scriver (version française) (Video capsule about Dr. Scriver here.)

The geneticist and the grocer: Charles Scriver, Arnold Steinberg and the healing power of food (2017)

Fiftieth anniversary of the collaboration between Mr. H. Arnold Steinberg and Dr. Charles Scriver

Medical Genetics at McGill: The History of a Pioneering Research Group (CBMH/BCHM, Volume 30:1 2013 / p. 3)