By Gillian Woodford

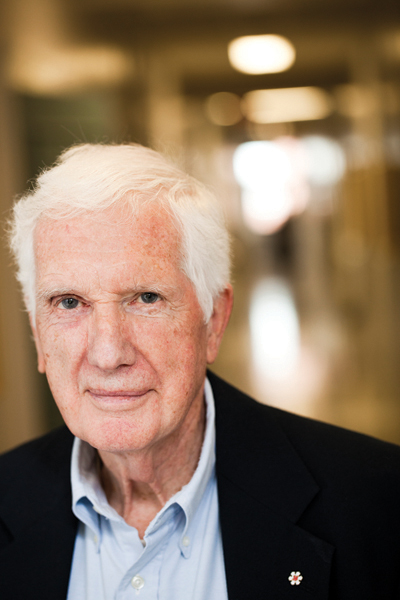

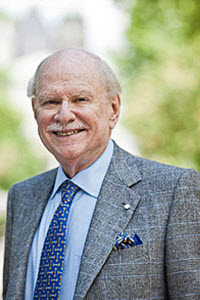

When a pediatrician specializing in genetic metabolic disorders and a philanthropist from a grocery dynasty teamed up to tackle two food-related public health issues, a lifelong bond was formed. Dr. Charles Scriver and Arnold Steinberg first came together to fight the high rate of rickets among poor Montreal children by getting vitamin D added to bottled milk. A few years later they founded a distribution centre for the nutrition products essential to children with rare metabolic disorders. Both changed the lives of those children forever.

Family Footsteps

The two first met when Dr. Scriver approached Mr. Steinberg of Steinberg’s supermarket chain and a member of the board of governors of the Montreal Children’s Hospital Research Institute, about the rickets problem. Dr. Scriver had recently embarked on a study there using a new technique called chromatography to analyse urine samples from every child that visited the hospital.

Over the course of the next few years Dr. Scriver noticed a pattern: “There was an increase in amino acid content in urine samples during certain periods of the year, namely late winter to late spring,” he says. “We noticed that it occurred in young infants and it disappeared as the infant got nutrition that contained vitamin D.” X-rays showed that these babies had rickets – their bones had the classic malformations associated with the disease.

After a bit more digging, Dr. Scriver discovered that the babies with rickets, generally from poorer families, “were being fed bottled dairy milk,” he says, unlike more affluent families who were giving their infants baby formula fortified with vitamin D. Around the same time, neighbouring Ontario and New Brunswick added vitamin D to their bottled milk in 1965 and saw an immediate decline in rickets cases.

Realizing he had a public health problem affecting thousands of Quebec children on his hands, Dr. Scriver headed out of his lab to lobby for vitamin D to be added to bottled milk in Quebec. He spoke before the Castonguay Commission in 1967 and within three days had a call from the Ministry of Health. By 1969 vitamin D was being added to bottled milk across Quebec. “But I did not succeed in getting vitamin D into the milk marketed in Montreal,” says Dr. Scriver. “So what was going on in Montreal? The person who was the CEO of milk marketing said ‘I will not contaminate my pure and beautiful milk with an oily substance like vitamin D.'”

The doctor was stymied. He decided to go see Arnold Steinberg. “He said, ‘I think I have a solution. Give me a couple of weeks and I’ll let you know when I get back,'” recalls Dr. Scriver. “He came back and said ‘Problem solved.’ I said, ‘What happened, Mr. Steinberg?’ He said ‘No vitamin D in the milk, no contract.'”

“Arnold was just one of these people who could solve problems,” says Dr. Scriver. “He knew how to do it and did it gracefully. And I’ve been a fan of his ever since.”

The pay-off in terms of public health was huge: cases of rickets in Quebec went from one in 200 to one in 20,000 virtually overnight.

Odd Things

That same year, 1969, Dr. Scriver and a group of medical geneticists created the pioneering Quebec Network of Genetic Medicine to screen newborns for congenital disorders. Dr. Scriver by this time was specializing in inborn errors of metabolism, a subset of genetic diseases. “When I started at McGill, the general understanding was that genetic diseases are like stamp collecting,” says Dr. Scriver. “They’re odd things so why bother about them because you can’t do anything about them.”

Dr. Scriver and his colleagues refused to accept this and, closely studying individual patients with recognized inborn errors of metabolism, began to work out what was causing these disorders. “We showed that if you modified the environment and modified the nutritional experience and added an appropriate chemical to their diet they grew up without their disease and therefore their condition was treatable. It may not be curable but it was treatable,” explains Dr. Scriver.

Meanwhile, the new screening program was turning up more and more cases, but the nutritional formulas required to treat them were hard to get in Canada. “We developed a national resource to make it possible to obtain the special diet products, import them into Canada and to distribute them safely to the affected families,” says Dr. Scriver. “How did we develop the resource? We went to Arnold Steinberg. We said, ‘You’re very good at marketing and setting up all the things that you do. Could you become the home for the genetic disease treatment program that we want to establish in Canada?’ He said ‘Yes.'”

Mr. Steinberg provided advice, funds and the space for the National Food Distribution Centre for the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases, known simply as “the Food Bank,” and became its founding president in 1974. A panel of experts from across the country agreed to make the Food Bank the sole authorized distributor of these products and limit the number of specialists authorized to prescribe them, in order to persuade the government to allow them to import the products as food (classing them as drugs would have incurred even more red tape). In addition, the Food Bank allowed specialists across the country to share their knowledge about these rare diseases by keeping a database of patients. The program, based in Longueuil, continues to this day.

“And so that was experiment number two with Arnold, that just changed the world for some people,” says Dr. Scriver.

December 20, 2017