New treatment under development by Professor Karine Auclair and Assistant Professor Andréanne Lupien could potentially treat intracellular infections without the need for traditional antibiotics

Although they were only used for the first time in 1910, antibiotics have become the foundation of modern medicine. In a world without antibiotics, a simple paper cut could lead to a deadly infection and infectious diseases were the leading cause of death. By some estimates, the invention of antibiotics have extended the average human lifespan by 23 years in the past century.

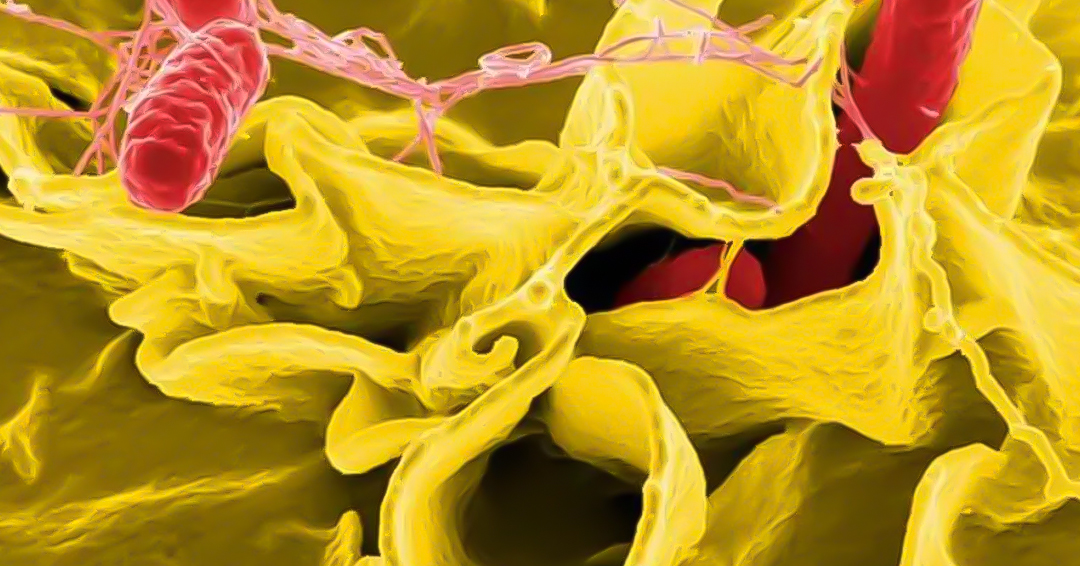

But increasingly, microbes are resistant to antibiotics, a trend that is becoming one of the fastest growing health threats of the 21st century. Commonly referred to as “superbugs,” the rising rates of resistance combined with few new treatments in the research pipeline mean that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is on track to become one of the leading causes of death globally, projected to reach 10 million deaths a year by 2050.

In this context, Karine Auclair, PhD, Professor in the Department of Chemistry; and Andréanne Lupien, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, are working to develop a novel treatment for intracellular infections that is free of antibiotics and facilitates the immune system’s ability to combat infections.

“The human immune system has many defenses,” said Auclair. “Our molecule affects the bacteria itself and weakens it. This makes it more vulnerable to human immune defenses and less likely to select for drug resistance.”

Taking a new approach

Immune cells have natural defenses against bacteria, including a substance known as itaconate. But bacteria have evolved to counter its effect by breaking it down and using the resulting molecules as a food source thus sustaining the infection. Auclair and Lupien are working on a molecule that inhibits the itaconate degradation pathway.

“The concept behind the technology is fantastic,” says Dao Nguyen, founder and Director of the McGill AMR Centre. “It’s really tackling therapy against bacteria through a completely different angle. What is unique about the Itaconate project is that it doesn’t directly tackle the bacteria, it’s co-opting a mechanism that our own immune cells are using to make the bacteria more sensitive to your immune cells.”

Major public health concern

AMR is a natural process, but it is accelerated by overuse of antimicrobials in preventing or treating infections. This is due to the widespread use of antibiotic treatments in people and animals. Antibiotic treatments are the cornerstone of many medical procedures and are not just prescribed to treat infections, but also prophylactically, such as for patients undergoing chemotherapy or prior to high-risk surgeries like c-sections and hip replacements.

“AMR is a major public health concern that is being described as a silent pandemic. One of the challenges that is unique to AMR is that there is very little industry support, and large pharmaceutical companies are not investing in new antibiotics because it is not profitable,” explains Dao Nguyen.

Due to this lack of industry investment, most innovations in the past decade have come from academic labs or small start-up companies.

Much-needed support

Lupien and Auclair are supported by the McGill Innovation Fund (MIF) in their journey from the lab to the market with a Discover award ($25,000) in the MIF’s third cohort. They also received $25,000 from the McGill AMR Centre as a supplemental award.

“This year, since the MIF partnered with the AMR Centre, we felt it was a good opportunity for us to get involved,” said Auclair. “The drug development process costs millions of dollars so we are looking for a licensee that can invest in the product. However, in order to do that they need to see preliminary data which the MIF and AMR is giving us the funding to collect.”