Support services for homeless people with mental illness in Canada’s biggest cities cost more than $55K a year per person on average, study finds

McGill Newsroom

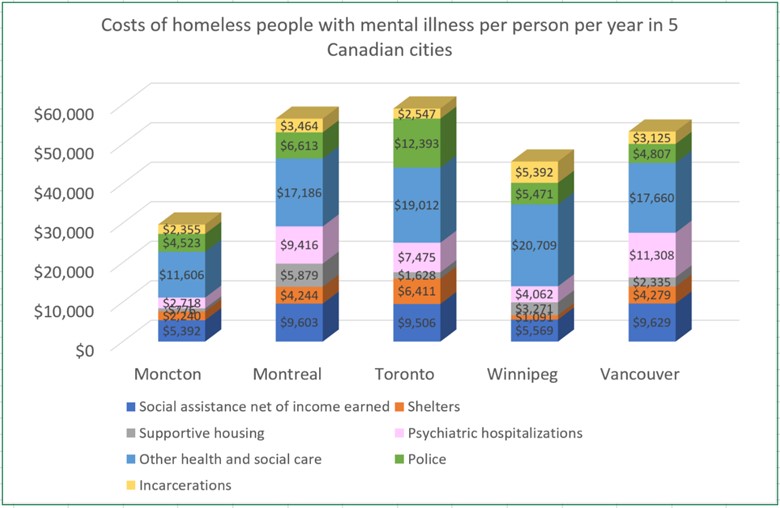

Health, social and judicial services for homeless people with mental illness cost society more than $55,000 per person per year, on average, in Canada’s three largest cities — a finding that suggests funds could be more effectively allocated to preventing and curtailing homelessness, according to McGill University health economist Eric Latimer.

Latimer is the lead author of a new study, published in the journal CMAJ Open, that presents the first comprehensive evaluation of how much major Canadian cities spend on homeless people with mental illness. It also compares the level of spending, and where the money goes, in five cities across the country.

Among the findings: The larger cities (Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver) provide more services and spend more per person than the smaller cities (Winnipeg and Moncton). And different cities spend the money differently. For instance, Montreal spends almost twice as much per person on supportive housing as the next highest city (Winnipeg), while Toronto spends nearly double what the next highest city (Montreal) does on police services and court appearances.

An estimated 35,000 Canadians are homeless on any given night, and over 235,000 experience homelessness over the course of a year.

The findings “raise the question of whether there might not be a smarter way of spending all that money,” Latimer says. “Other studies suggest that there are.”

The analysis was carried out as part of At Home/Chez Soi, an experimental research project comparing an intervention called Housing First with the services that are usually delivered to homeless people in five Canadian cities. Researchers from several other universities across Canada contributed to the study.

The Housing First program provides subsidized apartments on the private rental market and gives people long-term supports to help them get their lives together. An approach known as Critical Time Intervention, first developed in New York City and since used in many countries, helps people who recently became homeless to get out of homelessness quickly.

Programs of that sort “might end up costing a little more, at least in the short run, but they could make the system much more effective overall,” says Latimer, a professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry and researcher at its affiliated Douglas Mental Health University Institute.

_____

Funding for the study was provided by Health Canada.

“The costs of services for homeless people with mental illness in five Canadian cities: Results from a large prospective follow-up study,” Eric A. Latimer, et al. CMAJ Open, DOI:10.9778/cmajo.20170018

August 8, 2017