Remembering Dr. Edward William Archibald, an advocate for academic rigour and empathy in surgery, and the first Chair of McGill’s Department of Surgery.

Dr. Edward William Archibald (MDCM’1896), known both as Canada’s first neurosurgeon and the father of thoracic surgery in Canada, defied labels in his career as an innovative and compassionate surgeon and scientist. Dr. Archibald was the first chair of McGill’s Department of Surgery in 1923, established a program in Experimental Surgical to embed surgical research into the teaching hospital, advocated for higher standards in surgical training, and wrote treatises to advance neurosurgery, surgical treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis and knowledge of pancreatic diseases.

Griselda Christmas (BA’39), Dr. Archibald’s youngest daughter, passed away in January 2023 in Victoria. She was a recent donor to the McGill24 Challenge Fund and a $50,000 Fellowship was created on her behalf in her father’s name before she died. The Fellowship will support a graduate student in surgical research as of the 2023–2024 academic year.

Dana Wessel and Martha Lloyd-Smith, Christmas’s daughters, have been researching their grandfather’s life through his letters, writings, and accomplishments. Dana and Jim Wessel (MBA’67) have also contributed $100,000 in Dr. Archibald’s name to provide formal leadership training for surgeons. The three-month Leadership Course for Surgeons is a joint initiative with the Desautels Faculty of Management intended to help surgeons succeed—as Dr. Archibald did—in their various roles as leaders building clinical, research, and training programs.

Dr. Liane Feldman (MDCM’93, PGME’00) is the current Edward W. Archibald Professor and Chair of the Department of Surgery. Dr. Feldman, Dana Wessel, and Martha Lloyd-Smith spoke to FMHS Focus in January 2023—almost a century since the creation of McGill’s department of surgery by Dr. Archibald.

Dana Wessel: Dr. Feldman, what is known about my grandfather at McGill?

Liane Feldman: He created an academic department of surgery that continues to this day. There are at least three core elements that go into an academic department. First, there is clinical excellence and clinical innovation—developing and evaluating procedures and their outcomes. Then, there is research, and certainly Dr. Archibald was an early proponent of the importance of science in surgery. He began our surgical research program, including a graduate program, which he called experimental surgery, in 1929. Almost 100 years later, it’s still going strong. We now have over 200 students in our graduate program which this year will be renamed “Surgical and Interventional Sciences”. And number three, teaching and training the next generation. Dr. Archibald had important ideas about how surgeons should be trained, and he felt the system he grew up in was inadequate. Many of his opinions resulted in changes to training and a speech he gave led directly to the creation of the American Board of Surgery that certifies surgeons in the United States. He helped gain international stature and recognition for the Department of Surgery.

FMHS Focus: Growing up, Dana and Martha, what did you learn about your grandfather as a person?

Martha Lloyd-Smith: Our mother was not one to talk about her upbringing. We got general impressions that her household was busy with important people coming and going, but I didn’t get a huge sense of what our grandfather was like.

DW: He died when I was three, so I didn’t know him. But I know he encouraged his daughters to do what he himself had done, that is, to go abroad for a learning experience, to be a well-rounded person. They were all, as he was, avid readers and were given a lot of freedom.

MLS: He encouraged his daughters to develop skills; one was a pianist, another a violinist, one was a fencer.

DW: From what I read, he was a calm and courteous person throughout everything. We never really talked about his accomplishments. I remember, as a child, walking on the road with my mother. A total stranger rushed up to her and said, “Your father saved my life.” I was maybe five, but Mum just said, “That’s very nice. Thank you.” I remember her also saying many years ago, “We didn’t always have money, because he didn’t always bill his patients.”

Why was it important for you to make a contribution to the Dr. Edward Archibald Fellowship in Surgery on behalf of your mother, Griselda?

DW: My mother, Griselda Archibald Christmas, graduated from McGill with a BA in 1939 and hoped to follow in her father’s footsteps with a medical career. However, she got sidetracked by World War II, children, a husband in the Navy, no time and no money to pursue her education and interests. She became aware of our conversations involving her father, and together we decided that augmenting the Fellowship would remind more students of the legacy of Dr. Archibald. She believed providing support for more students who wanted to study the science of surgery would honour her father, and she was very touched by this gesture, expressing gratitude that this had been arranged in her name.

He was also a veteran and was influenced by his peer, John McCrae (who wrote “In Flanders Fields”). What do we know of their relationship and his time with the Canadian Army Medical Corps?

MLS: John McCrae became part of his household for six years. He was part of the family, he loved and would play with Edward Archibald’s daughters, and, apparently, was a great storyteller. His letters, written during the war, always mention the girls with fondness. At that point, John McCrae had become a doctor, pursuing medicine in Montreal. He and my grandfather went off to war together. They were close already, but their war experiences tied them closer, and they corresponded frequently. John McCrae became the Chief Medical Officer of the No. 3 Canadian General Hospital, so they worked together.

DW: Their military career also influenced McGill’s reputation. McGill was the first and only university medical team to be sent to Europe in the war years.

LF: In World War I, the McGill hospital had thousands of beds, and so many from McGill, from students to professors, signed up to help.

MLS: In one of the letters, our grandfather expressed a huge amount of pride that their medical unit had the lowest death rate of all the hospitals on the front. It was directly attributed to the skill and techniques of Majors Walter Henry Phillip Hill and Archibald. I guess he was proud of that.

LF: A lot of the development of surgery is based on war experiences, and that probably informed Dr. Archibald, who is the father of thoracic surgery in North America, but was also the first neurosurgeon in Canada.

Dr. Archibald started in neurosurgery, but he advanced treatment of TB and thoracic surgery, as well as techniques to treat pancreatic diseases—all quite separate areas of study. Was this common for a doctor?

LF: It was a different time. There weren’t specialties of surgery as there are now. Chest surgery wasn’t separate from abdominal or even neurosurgery. It was all surgery. In addition to his work in neurosurgery and thoracic surgery, Dr. Archibald did research in pancreatitis, which is a common problem in general surgery, and experimented with concepts of sphincteroplasty—widening the sphincter of Oddi, the part of the bile ducts that empties into the pancreas. It’s a very common procedure done now with endoscopic techniques. He developed the concept beginning from a theory of how gallstones cause pancreatitis. This is an example of a scientific approach to difficult surgical problems. It begins with a clinical problem and then going into the lab, creating animal models of pancreatitis to be able to study it. Dr. Archibald was the father of surgical research in Canada. The idea was to bring in scientists to collaborate with clinicians in the hospital setting and that this culture of scientific inquiry would benefit patients as well as improve surgical training. It was important to the evolution of the profession of surgery, regardless of the specific disease or procedure being studied. Dr. Archibald was very influenced by his time in Germany where he was introduced to the idea of applying scientific methods in surgery, including lab research, studying outcomes, and peer review. He brought that back and translated it into developing his own program at McGill.

Dr. Archibald was a McGill professor, a surgeon, but also a lifelong learner. Why do you think he continued to investigate even in his last years?

LF: He was a scientist. And that’s the difference between continually learning from your own patients and refining your own techniques, which is, of course, laudable, versus moving an entire field forward, which requires a rigorous analysis of your results, good and bad, and presenting them to the wider community, which may change the practice of surgery in general. That’s the difference between a good surgeon for his own community and someone who is going to transform the profession. For example, with thoracoplasty, which is a procedure that Dr. Archibald was one of the first to perform for the treatment of tuberculosis, he analyzed his results to find out who would benefit from it. The mortality rates were very high—in one of his groups of patients, it was 25 percent. To meticulously track your results and present them for peer review, as he repeatedly did, including at the American College of Surgeons, requires applying scientific methods to clinical work which can then impact others more widely.

Dana, why did you and your husband decide to support leadership training at McGill? Why do you think this kind of training is important for surgeons?

DW: My husband, Jim Wessel, and I have two major affiliations with McGill. My family has a century-old history with the medical faculty. And both Jim and I have a history with the business school, where I was an employee of the Graduate School of Business Administration at Purvis Hall back in its conceptual years. The involvement of the Desautels Faculty of Management in the leadership training program for surgeons was brought to our attention by Dr. Feldman. We were immediately supportive. Doctors require different skills from those taught and experienced through medical school and private practice. Our own family physician has discussed his struggles with the business issues of his practice. Collaboration between the Department of Surgery and the Desautels Faculty of Management is, in itself, an innovative approach for future success of physicians, both within the operating room and within their community.

What is the significance of the Edward W. Archibald Professor and Chair title?

LF: The Edward W. Archibald Professor and Chair is an endowment (established in 1949 with an initial funding of $35,000) that was created to celebrate the legacy of Dr. Archibald. It’s a way to link the foundational values that began 100 years ago with Dr. Archibald to the academic mission in our department even today.

DW: It certainly makes his family proud. It was exciting to learn that the Chair not only still exists, but that it has grown. The research work that Dr. Feldman’s team is doing is valuable and relevant to the scientific approach to surgical procedures, and precisely what Dr. Archibald himself believed in and had dedicated his life to so diligently and brilliantly.

MLS: If I could share a quote, our grandfather once said: “To gather knowledge and to find out new knowledge is the noblest occupation of the physician. To apply that knowledge with understanding to the relief of human suffering is his loveliest occupation.” I think that sums up how he felt about his calling in medicine.

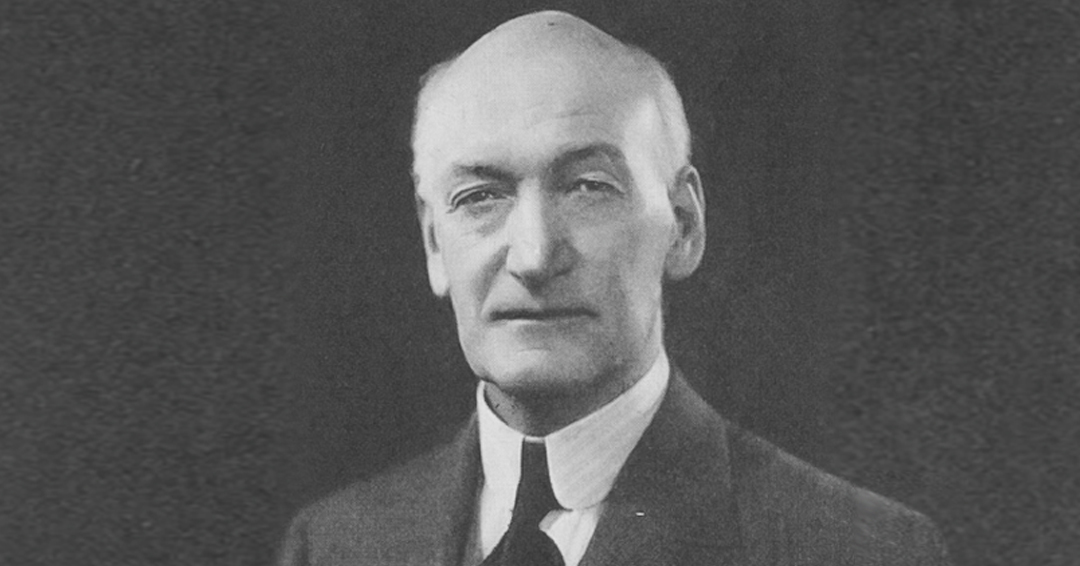

Image by McGill University Archives (PR028717).

Edward William Archibald, graduate of Medicine, 1896.

Born in Montreal in 1872, Dr. Archibald graduated from medical school at McGill University and trained as a young surgeon at the new Royal Victoria Hospital. His postgraduate studies brought him to France and the then German Empire, where he learned from Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, who was at the forefront of modern surgery and aseptic techniques.

He married Agnes Maud Black Barron, a musician, in 1904, the same year he began an appointment at the Royal Victoria’s Department of Surgery. They had four daughters, including Griselda Christmas.

Dr. Archibald returned to the Royal Victoria and was appointed to the surgical pathology department in 1901. From Europe, he brought with him a growing desire to advance science and preventative medicine through surgery, but his career was put on pause as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. His own experience as a tuberculosis patient in a New York sanatorium sparked an interest in improving treatment for the disease. He would become one of the first in North America to treat tuberculosis through thoracoplasty.

Early in his career, Dr. Archibald developed expertise in neurology and neurosurgery, which he studied in London, England, for several months in 1906. A few years later, he published his first neurosurgery monograph called Surgical Affections and Wounds of the Head. He later recruited Wilder Penfield and William Cone to open the Montreal Neurological Institute, which allowed Dr. Archibald to focus on thoracic surgery. He also recruited Norman Bethune, a young thoracic surgeon at the time.

Dr. Archibald served with the Canadian Army Medical Corps from 1914 to 1916, alongside his friend, Dr. John McCrae, who famously authored the war poem “In Flanders Fields”. During the war, Dr. Archibald worked at the No. 3 Canadian General Hospital, known as the McGill unit, and was one of the first surgeons to perform a blood transfusion. Dr. Archibald, a patriot eager to contribute to the war effort, wrote that he felt “like a scalpel on a tray, waiting to be used when the time comes and just keeping sharp” before working at the Canadian Casualty Clearing Station near the front line. He returned to the army medical corps in World War II, gathering research for a book on war surgery until 1944, even though by this point he was in his 70s. He died in Montreal in 1945, recognized internationally for his dedication to medicine.

In his obituary to Dr. Archibald, Dr. Jonathan Campbell Meakins, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the time, and one of the McGill doctors who served with Dr. Archibald at the No. 3 Canadian General Hospital, wrote that “He appreciated how easy it is to forget mistakes and remember successes.”

Meakins also wrote of his friend: “‘Eddie’ as he was affectionately called, was always expected to be late. This was not due to a disorderly mind but to his unbounded sympathy and love for his fellow man. No task was too great; no patient too humble; no colleague too junior for him to give his time unexpectedly and in full measure.”