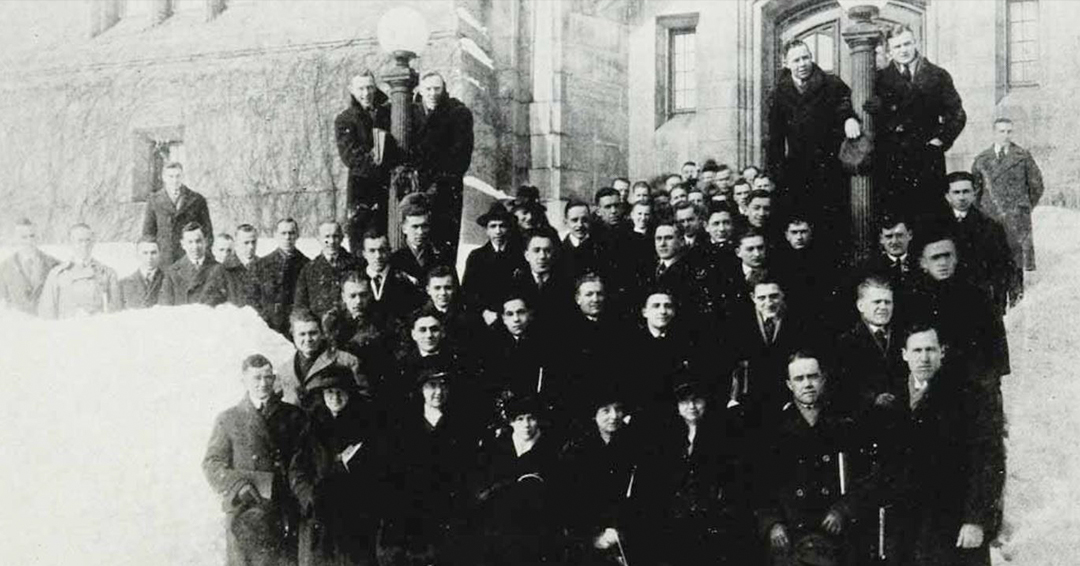

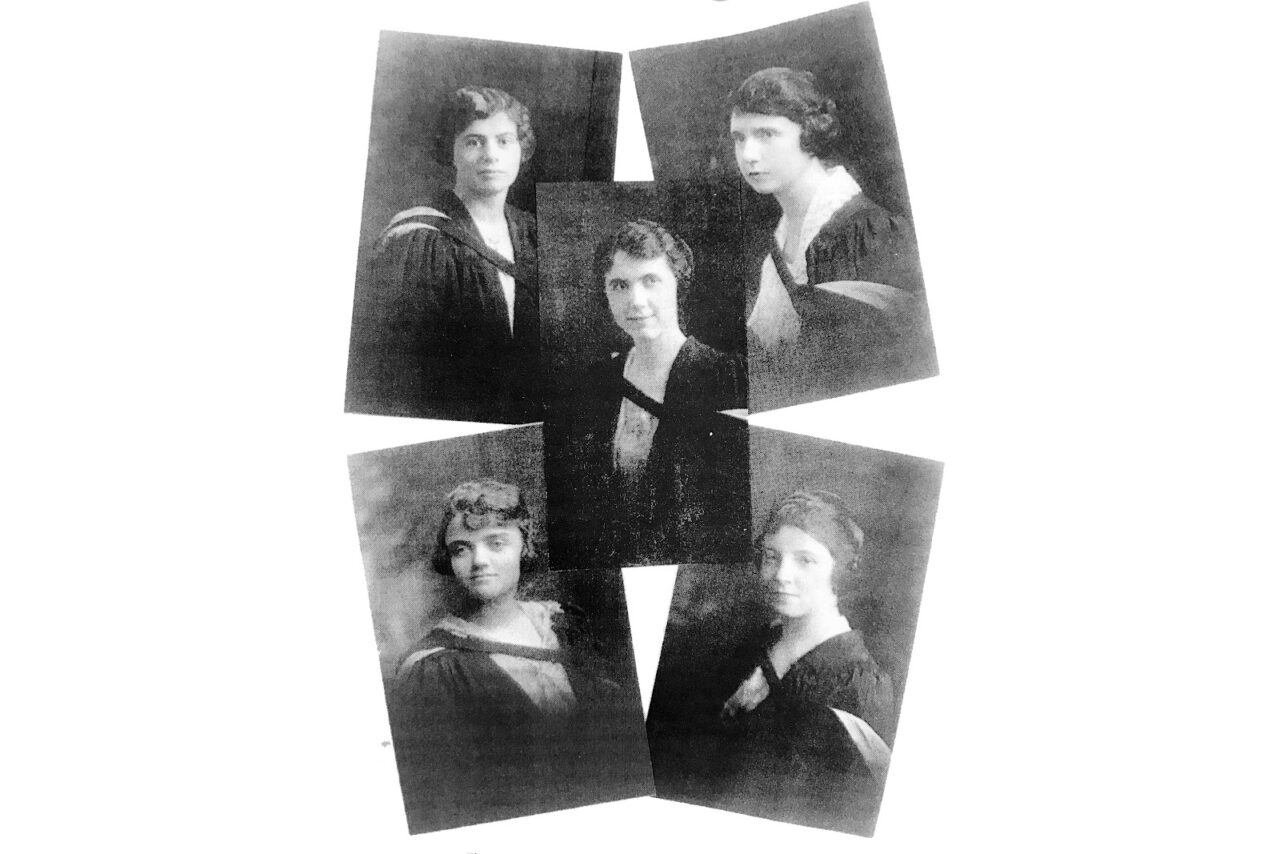

One hundred years ago, at the 1922 Spring Convocation, five brave and determined young women – Eleanor Percival, Jessie Boyd, Lilian Irwin, Winifred Blampin and Mary Childs – received their MDCM degrees alongside their 121 male peers (the photo above is a detail showing them at the front of the Medicine Class of 1922; the full class photo is below). At the 2022 Spring Convocation, by contrast, the Medicine Class consisted of 180 students, 56.1% female and 43.9% male.

To celebrate the milestone, none other than Maude Abbott – who was herself denied entry to McGill’s medical school and fought hard her entire career to advance the place of women in medicine – hosted a victory reception for the five at the Ritz-Carlton. Jessie Boyd later wrote: “It is difficult to convey the joy and triumph of Dr. Abbott at that graduation in the spring of 1922 when McGill bestowed for the first time her regular medical degree of M.D., C.M. on five women medical graduates. In 1910 McGill had honoured Dr. Abbott with a McGill M.D., C.M. (honoris causa) recognizing her work and reputation and there is no doubt that her reputation had some influence on the final decision to admit women to the study of medicine.” (From her chapter on Maude Abbott in The clear spirit: twenty Canadian women and their times, edited by Mary Quayle Innis, page 149.)

The female students were not exactly welcomed with open arms when they were officially admitted to the medical program in 1918. Boyd’s house was famously picketed by disgruntled male peers who demanded the five withdraw. The protestors were possibly inspired by a group of male students at Queen’s University who succeeded in 1883 in getting female students expelled from its medical school. But the McGill protest did not succeed nor did it sway the administration – which had been under pressure for decades to admit women, finally doing so to fill openings left by male students fighting overseas – and the women remained.

“We were a fairly serious crowd, about half of us war veterans, but in one way we were unique, it was the first medical class to which McGill admitted women,” recalled Harold Griffith, the pioneering anaesthetist and also a member of the Class of 1922 (quoted in Harold Griffith: The evolution of anesthesia, page 27.) The new additions were also noted in the medicine section of the 1922 Old McGill yearbook: “We stand here now a fortuitous group of men and women, and as all such – a strange mixture of absurdity and good sense for the reader to judge which preponderates,” begins, with irony, the History of the Medicine Class of 1922. “We came – a curious conglomerate of youths and maidens, some thirsting for knowledge, others thirsting for something else…” But the returning soldiers – “a turbulent crowd… fresh from the wars” – seem to have largely overshadowed the diligent young women, fresh from wars of their own.

That the small cohort excelled in their studies may have led to their grudging acceptance. “At convocation in the spring of 1922 Jessie Boyd was second overall in the class of 126 and won the Wood Gold Medal for excellence in clinical medicine. Winifred Blampin won the first Senior Medical Society prize…. Thus two of the five senior prizes went to women,” note the authors of McGill Medicine, Volume 2: 1885-1936, page 109.

What became of the five after they left McGill? The McGill News offered the following update on four of the alumnae a couple of years after their graduation:

- Winifred Blampin is teaching bacteriology and pathology at the Women’s Medical College of Philedelphia, where she is Dr. Maude Abbott’s right-hand ‘‘man.”

- Jessie Boyd has been on the staff of the R.V.H. in pediatrics for the past two years. Her engagement to Dr. Walter Scriver, Med. ’21, has been announced.

- Eleanor Percival has just spent a year under Kelly at Johns Hopkins. She is returning to Montreal, where she will practice. She has an appointment to the staff of the gynaecology outdoor of the M.G.H.

- Mary Childs is remaining on the staff of the metabolism department of the M.G.H. for another year.

Eleanor Percival and Jessie Boyd led particularly distinguished careers in Montreal.

After her training in Baltimore in obstetrics and gynaecology, including in the new field of radium to treat cancer, Eleanor Percival became a pioneer in the field in Montreal. She became the first female physician at the Montreal General Hospital where she ran the hospital’s radium service, specializing in cervical cancer. (Read her report Carcinoma of the Cervix: A report on 100 cases treated at the Montreal General Hospital, 1925-1929 from the CMAJ here.) Learn more about Dr. Percival’s career at the Montreal General Hospital’s online 200th anniversary exhibition.

Jessie Boyd, while working as a physician at the Royal Victoria Hospital, undertook groundbreaking postgraduate research in sickle cell anemia that is still cited today. She later did pediatrics training at Harvard and Boston Children’s Hospital and is thought to be Quebec’s first female pediatrician. She ran a busy and popular practice in Montreal while also working as an attending at the Royal Victoria Hospital (where she became Pediatrician-in-Chief) and later the Montreal Children’s Hospital. She became a professor of pediatrics at McGill and was elected the first female President of the Canadian Paediatrics Society in 1952. McGill conferred upon her an honorary doctorate, DSc honoris causa, in 1979.

She did indeed marry Walter Scriver and they had one child together, Charles, who followed in his mother’s footsteps and became a renowned pediatrician and genetics researcher. “Dr. Jessie,” as she was known to her patients and their parents, chose, controversially, to continue practising after becoming a mother, later telling her son: “I have been given the privilege of being able to study medicine at McGill University. I owe it back to society to uphold that privilege.” (Quoted in our interview with Dr. Scriver in a story about his mother.)