Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy, the distinguished physician aboard the Starship Enterprise on the classic television show, “Star Trek”, would surely be fascinated by McGill University’s Space Medicine Interest Group, co-founded by Adi Mithani, who is currently pursuing a medical degree and a PhD in biomedical engineering, simultaneously.

While space medicine primarily focuses on physiology, preventive and emergency medicine and toxicology, a significant chunk of the research has contributed to the development of technology and procedures that provide treatment for the general population.

“The goal is to increase awareness of the field of space medicine to medical students, in terms of how they can take their education in medicine and not only apply it to people living in austere environments, but also to regular people here on Earth. So, it’s not just space, but also people living in remote communities,” Mithani says.

Space medicine research has produced several innovations that benefit overall healthcare. Lightweight, portable medical devices provide point-of-care diagnostics for urine, renal, electrolyte and glucose analysis. Telemedicine and telehealth technologies improve access to healthcare, especially in underserved regions.

Mithani points out that space medicine has also contributed to significant developments in cancer therapy. The reduced gravity environment of space accelerates tumour stem cell growth, which allows researchers to study the process on shorter timescales and determine the points within a cell’s life where they can intervene. “The environment has also been shown to influence tumour biology, migration of cancer cell lines, modulate glucose metabolism, and the morphology of cancer cells. Whether simulated through parabolic testing or real, it provides a unique and valuable environment for the study and treatment of cancer.”

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) recently hosted the Space Medicine Interest Group at its headquarters in Longueuil, Quebec, for a rundown on its current projects including the ‘Health Beyond Initiative,’ an effort to stimulate and support innovative and sustainable solutions that will address the healthcare challenges faced by astronauts in deep space, and people living in remote communities across Canada. The meeting laid the foundation for a collaboration between the two groups.

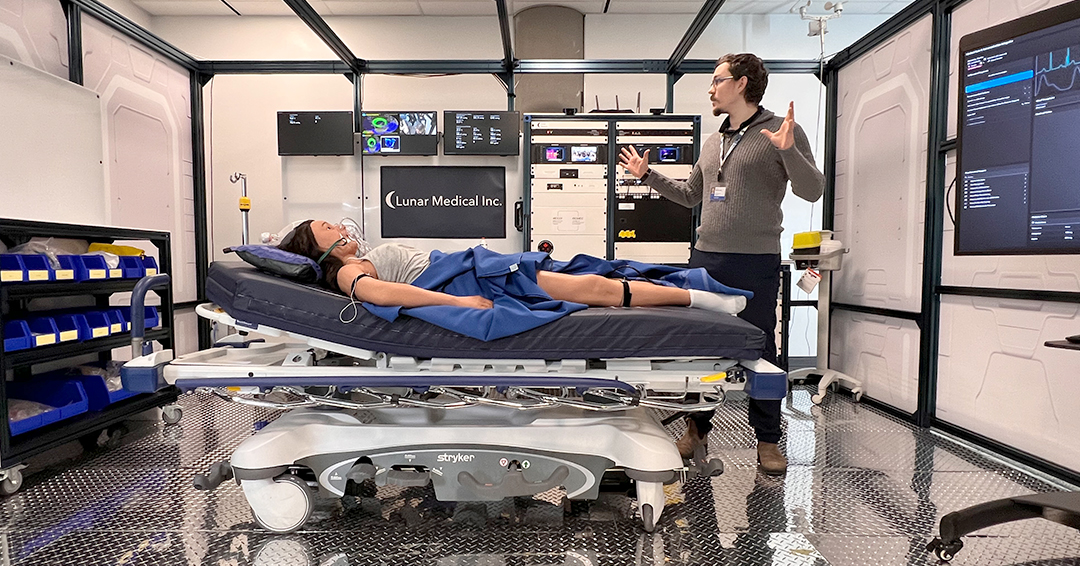

“Their emphasis is on deep space health,” Mithani says. “The Government of Canada is trying to find new technologies that are designed to address the lack of healthcare in remote communities which reflect conditions you observe in space when there are no doctors available. We discussed the newly developed Connected Care Medical Module (C2M2) system (see image) driven by artificial intelligence, that may be a transformative force in crew health management. This advanced system not only diagnoses ailments, but also recommends treatments and provides guidance on medical procedures. It has the ability to adeptly guide crew members through tasks like conducting an electrocardiogram (ECG), with very little medical training. It is essentially a clinical decision support system that integrates with several different data sources to provide a comprehensive patient assessment. This and other technologies showcased during the visit will help to guide future medical students on the skills and education that will be required to contribute to future developments. They want to see more student involvement, not just engineers and technical, but also on the medical front.”

That desire faces a major hurdle, says Mithani, because most medical students are not familiar with space medicine, nor do they possess a technical background. “Whenever we say space, you think of astronauts, and there are very few of them. But the more you educate people about delivering care to remote communities, drawing parallels between what we’re facing on Earth and space, it draws more attention, and we’ve seen an increase in student interest.”

Mithani encourages medical students to study a technical discipline to increase their understanding of the technical aspects of space and medical technology. “This is why I’m pushing for a dual MD/MEng program at McGill, because while doctors and clinicians are very good at identifying health problems, when it comes to contributing to the technical development of a solution, including the feasibility or the utility of a device and its limitations, there is limited expertise.”

A better understanding will ultimately increase interest in the field and its potential benefits. “I want medical students not to be afraid of taking that leap of just learning something and trying something new, and seeing how it can have a much bigger impact than what they originally thought. So, the major goal of the Space Medicine Interest Group is to explore a new frontier.”

Perhaps the final frontier.