By Gillian Woodford

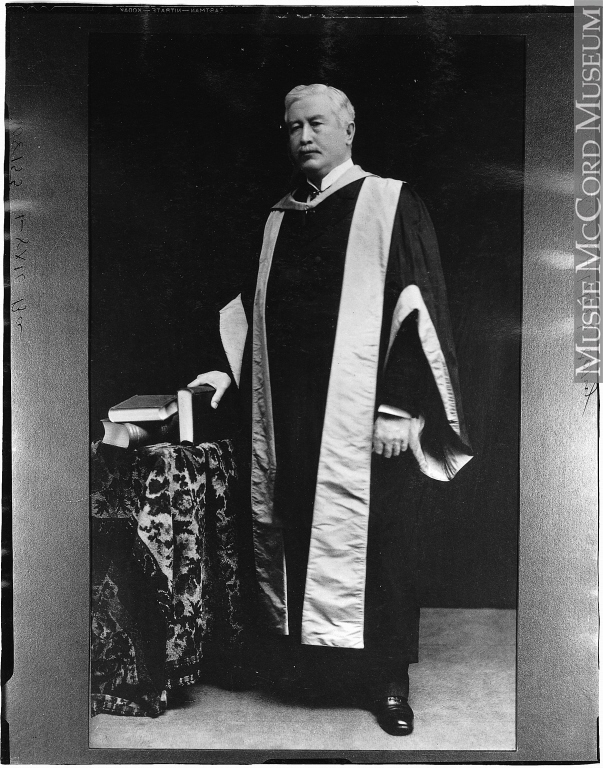

Dr. Thomas Roddick (1846-1923) is probably best known around McGill as the name behind the Roddick Gates, which his wife donated after his death. Perhaps less well known is that the former Dean of Medicine was the surgeon who brought antiseptic practices to Canada. Antisepsis drastically reduced rates of post-operative deaths from infection and quickly paved the way for more daring procedures, including abdominal surgeries.

When Dr. Roddick started his career in the 1860s, surgery was in a phase of radical technical change, but major operations were still rarely done, usually as a last resort because of the very real risk of deadly wound infections. Despite medical advances, such as anaesthetics, post-operative mortality was running as high as 80% for some interventions.

Antisepsis changed all that. “Before antisepsis, surgeons were not aware that micro-organisms were behind the fever that many of their patients died of after surgery,” explains Dr. Thomas Schlich, James McGill Professor in History of Medicine at the Department of Social Studies of Medicine at McGill. Louis Pasteur’s work on germs inspired a young English surgeon named Joseph Lister to investigate whether these micro-organisms were also the culprits behind wound infections.

Lister tested his theory by disinfecting compound fracture wounds with carbolic acid, which he had learned was being used to control typhoid outbreaks by decontaminating sewage. Lister reported at a meeting of the British Medical Association in 1867 that “during the last 9 months not a single instance of pyaemia, hospital gangrene or erysipelas has occurred in them.” *

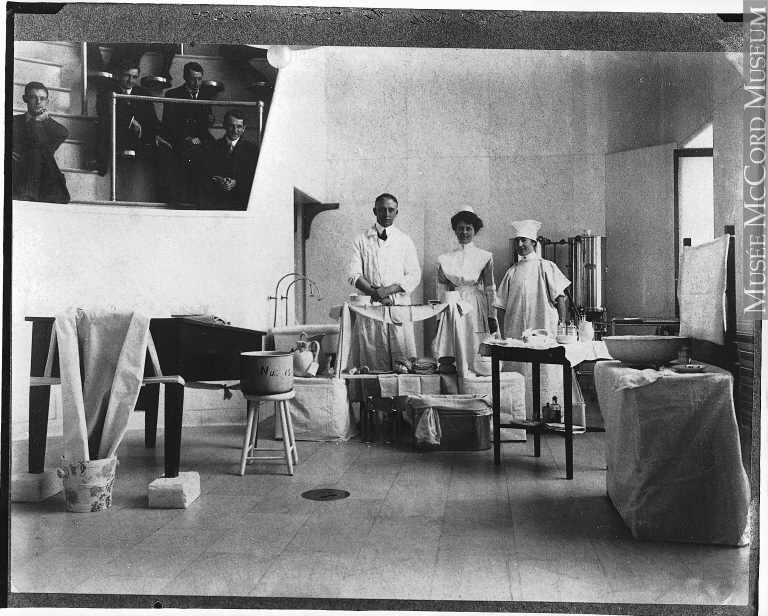

Based on these results, Lister developed an elaborate disinfecting system, involving a sprayer that doused everything and everyone in the operating theatre with carbolic acid, as well as gauze and catgut sutures soaked in carbolic acid. Surgeons and nurses also scrubbed their hands with the stuff.

Met with skepticism at home, Lister’s ideas caught on quickly abroad. In Montreal, young Thomas Roddick was appalled at the high mortality rate on the surgical ward. He visited Lister in 1872, just five years after the discovery of antisepsis, but as a junior doctor he had no influence to bring the new practice to Montreal. In 1877, after gaining full Operating Room privileges at the Montreal General Hospital, he returned to Scotland and London where he received full antisepsis training under Lister. He purchased the disinfecting apparatus, including the sprayer, and shipped it back to Montreal where he immediately implemented its use.

Practically overnight, Roddick’s post-operative mortality rate, which previously stood at around 50%, plummeted to 3%. Initially, skepticism reigned among his colleagues, as it had for Lister. “Opinion was split,” says Dr. Schlich. “There were surgeons who followed him, but many others thought antisepsis was useless.”

But Roddick didn’t give up and made antisepsis something of a crusade. He gave lectures and wrote papers and promoted the practice wherever he could. “He made sure he taught his students and colleagues,” says Dr. Schlich. Dr. Roddick also worked hard to standardize wound treatment practices in Montreal, so that it would be easier to evaluate what worked and what didn’t.

Roddick hadn’t been the first to try bringing antisepsis to Canada. Others had attempted a sort of ‘Lister light’ approach that only adopted certain aspects and therefore didn’t reduce infections and mortality to as great a degree. “Roddick’s particular contribution is that he was the first in Canada to do it comprehensively,” says Dr. Schlich.

The antisepsis era lasted about 10 years. “Eventually surgeons found the spray to be totally useless,” says Dr. Schlich. “They had thought the germs were in the air, but later realized direct contact with the micro-organisms was more important.” On top of that carbolic acid was quite caustic. “It was not good for the surgeons – many developed an allergy or intolerance and had to stop performing surgery,” says Dr. Schlich. Antisepsis was eventually replaced by asepsis, which focused more on preventing the germs rather than killing them, using good hygiene and sterilization practices.

“The existence of antisepsis contributed to surgeons being more courageous,” says Dr. Schlich. Within the next 25 years, many major operations, such as appendectomies, nephrectomies and hysterectomies, became part of the surgical repertoire.

* Quoted in “Joseph Lister: father of modern surgery,” Dennis Pitt, MD, MEd and Jean-Michel Aubin, MD, Can J Surg. 2012 Oct; 55(5): E8–E9.

June 20, 2017