This is the September installment of our series highlighting the McGill Faculty of Medicine’s contribution to the city of Montreal in honour of its 375th birthday.

By Gillian Woodford

Over the course of nearly two centuries, the hospitals that make up the McGill University academic health network have gone from fiercely independent private entities competing for funding and resources to publicly funded collaborative institutions whose watchwords are integration and consolidation.

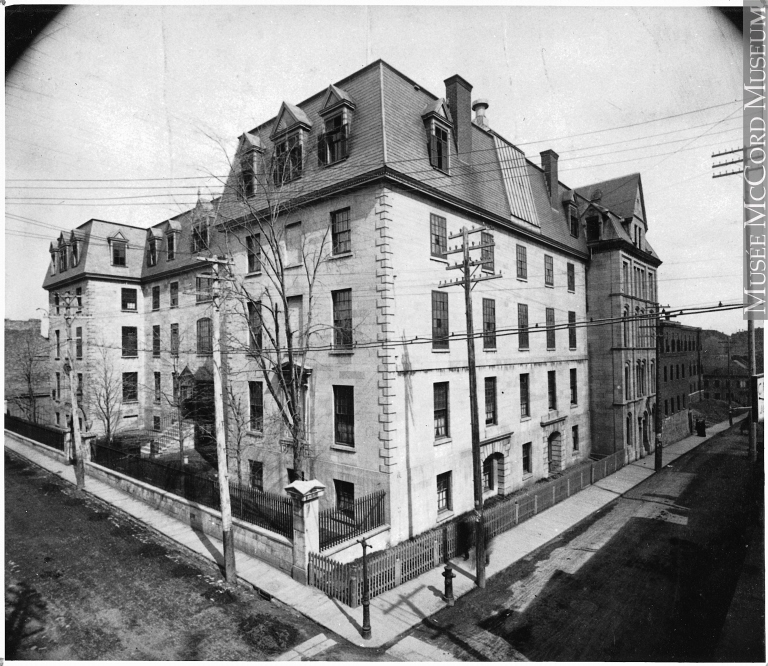

Most of the McGill-affiliated hospitals were established at a time when healthcare was funded by a combination of government support, endowments and donations from the community. The oldest is the Montreal General Hospital, founded in 1819, which predates McGill’s Faculty of Medicine (1829) and was its original and main teaching hospital – along with the University Lying-In Hospital after 1843 – until the Royal Victoria Hospital opened in 1893.

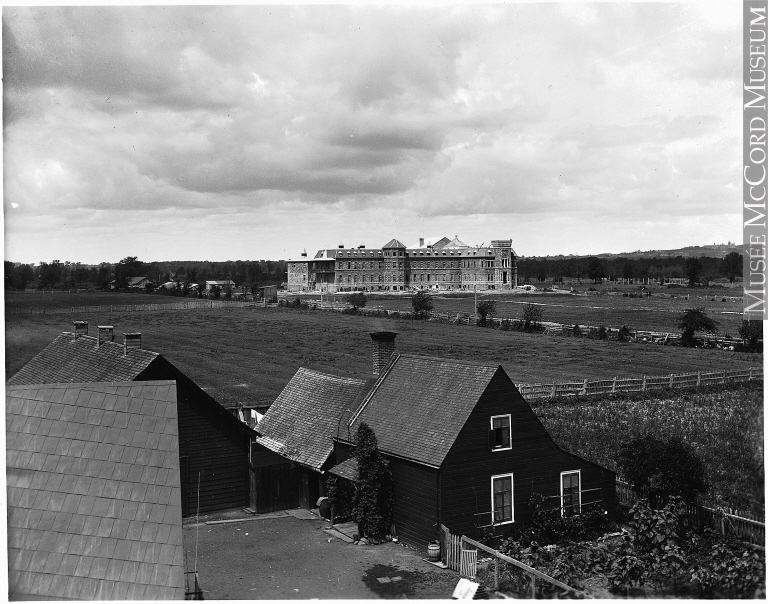

“[Rail barons] Strathcona and Mount Stephen built the Vic as a competing full-service hospital,” explains Dr. Richard Cruess, former Dean of Medicine (1981-1995) at McGill and co-author of two volumes on the history of McGill’s Faculty of Medicine. Intense rivalry informed the relationship between the two hospitals for over a hundred years. Faced with ageing facilities after World War II, an attempt was made to join forces to raise funds for new buildings for the two hospitals. It failed spectacularly. “The story is they couldn’t even agree on an agenda at the first meeting,” says Dr. Cruess.

Meanwhile the number of English hospitals had continued to grow, with many staffed by McGill faculty and often served as unofficial teaching hospitals. The Douglas Hospital, known at the time as the Protestant Hospital for the Insane, had been founded in 1881. It became a McGill teaching hospital in 1946, although medical students had been training there since 1900. The Montreal Children’s Hospital had opened in 1904 and became officially affiliated with McGill in 1920. The Royal Edward Institute, which later became the Chest Institute, was founded in 1909 to combat tuberculosis (TB) becoming a teaching hospital of McGill in 1932. Following the advent of antibiotics for TB in the 1940s it gradually shifted its focus to a wider range of respiratory diseases. The Shriner’s Hospital, which opened in 1925, and specializes in pediatric orthopaedics, is also affiliated with McGill.

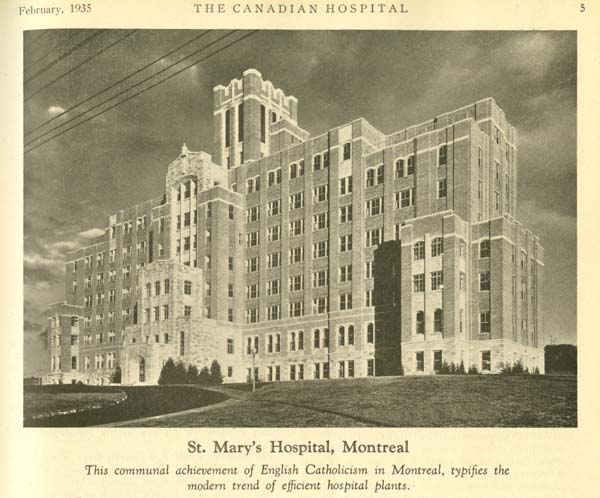

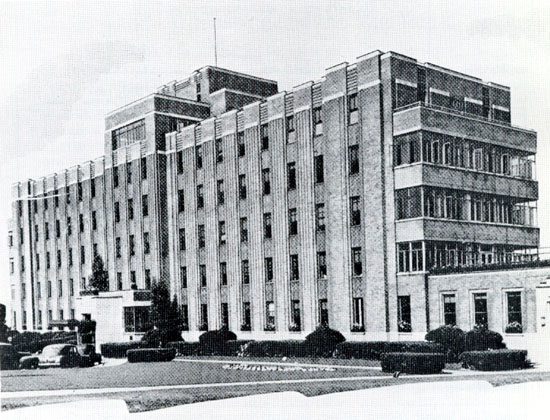

Despite falling in the middle of the Depression, 1934 was a particularly auspicious year for English-language healthcare in Montreal. St. Mary’s Hospital, which was founded in 1924, moved into its present location in 1934 built with funds raised by the city’s Irish-Catholic community; it later became a teaching hospital of McGill. Also in 1934, the Jewish General Hospital opened with money raised by Montreal’s Jewish community. Its full affiliation with McGill was granted in 1969.

Artist Unknown

Lastly, the Montreal Neurological Institute was also founded in 1934: “A promising superstar neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield had a concept to bring together scientists and clinicians around neurological diseases and he convinced the Rockefeller Foundation to fund it in the middle of the Depression,” recounts Dr. Cruess. Unlike the other hospitals, the Neuro was a McGill affiliate from its inception. That’s because the head of the Royal Vic and Dr. Penfield’s boss Sir Charles Meredith felt it was too big a financial risk for the Vic to take on at the time and so it was built under the direct auspices of the university and so it remains today.

After World War II, the network remained relatively stable, says Dr. Cruess. “They were competing, independent institutions with some collaboration, reasonable relationships between them but not much cross-over of staff.” Things stayed this way until the introduction of Medicare in Quebec in 1970. “The combination of the demands of modern specialty care whereby reasonable volumes are necessary just to be competent, and the government looking to get more cost-effective care, made it difficult to maintain two general adult hospitals, especially when they were only about 2km apart.”

Pressure on the network to consolidate administration and medical services eventually resulted in the voluntary merger in 1997 to form the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). The MUHC brought together the Montreal General and Royal Vic, who finally put aside their old rivalries, as well as the Neuro, the Chest Institute and the Children’s. The Lachine Hospital came on board in 2008. The MUHC completed its historic move to its new superhospital, the Glen site, in 2015, with the Royal Vic, the Children’s and the Chest Institute housed under one roof.

The impetus to create the MUHC came from within the hospitals and administratively the transition was smooth. The difficulties adapting were mainly at a personal level, says Dr. Cruess, who knows from his own experience as a longtime Royal Vic orthopaedic surgeon that such mergers can be a bitter pill to swallow.

“Part of the strength of the McGill Faculty of Medicine throughout the years has been the extraordinary loyalty the staff, nurses, doctors had to their institution,” he explains. “The people who worked at the Vic absolutely adored it, and those at the General and the Children’s felt the same way. To rupture that relationship wasn’t easy – and quite frankly I know that. I came to Montreal to go to the Vic with my wife, Dr. Sylvia Cruess. We absolutely loved the culture; we were a community.” He continues, “It’s not easy when you’ve been competing for years and you’re a 60 year old surgeon or psychiatrist and all of a sudden you have to move to the other hospital because that activity is being transferred. That’s very difficult.”

However, new bonds are formed and new loyalties developed, and Dr. Cruess says the mergers have had an enormously positive impact on patient care and outcomes in Montreal. He adds that the move to the Glen, although logistically complicated, wasn’t nearly as professionally difficult as the merger in 1997. “Most of the cultural shifts were well along before we moved to the Glen,” he says. “The move really brought people together.”

September 29, 2017