By Sol Inés Peca

Yojiro Yamanaka, PhD, Assistant Professor of Human Genetics at McGill University, has been awarded a $750, 000 grant by the CIHR to study embryonic development at McGill’s Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre. “I hope our study will shed light on the principal of mammalian development,” says Yamanaka.

–

When Yojiro Yamanaka was a child growing up in Japan, he wanted to be a zookeeper. But his general interest in the biology of the natural world eventually led him to discover scientific knowledge based on other people’s experiments. “I realized that I did not need to just understand and memorize, but I could question and participate. Since then, I followed have my curiosity.”

However, after graduate studies in Pharmaceutical Sciences and a PhD in immunology, round cells in test-tubes failed to peak that curiosity. Something was still missing – and it turned out to be the ability to directly observe the development of life on a cellular level.

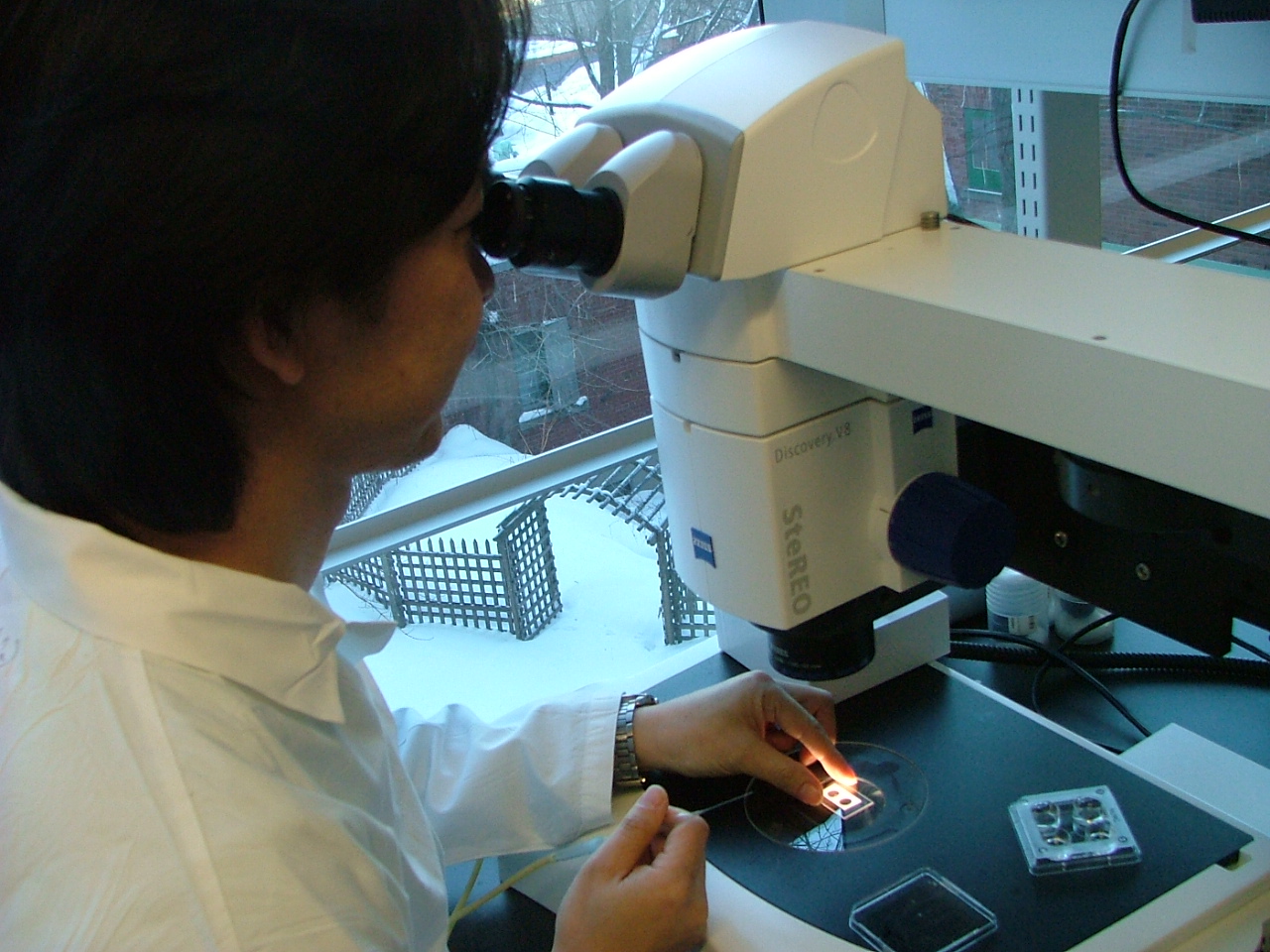

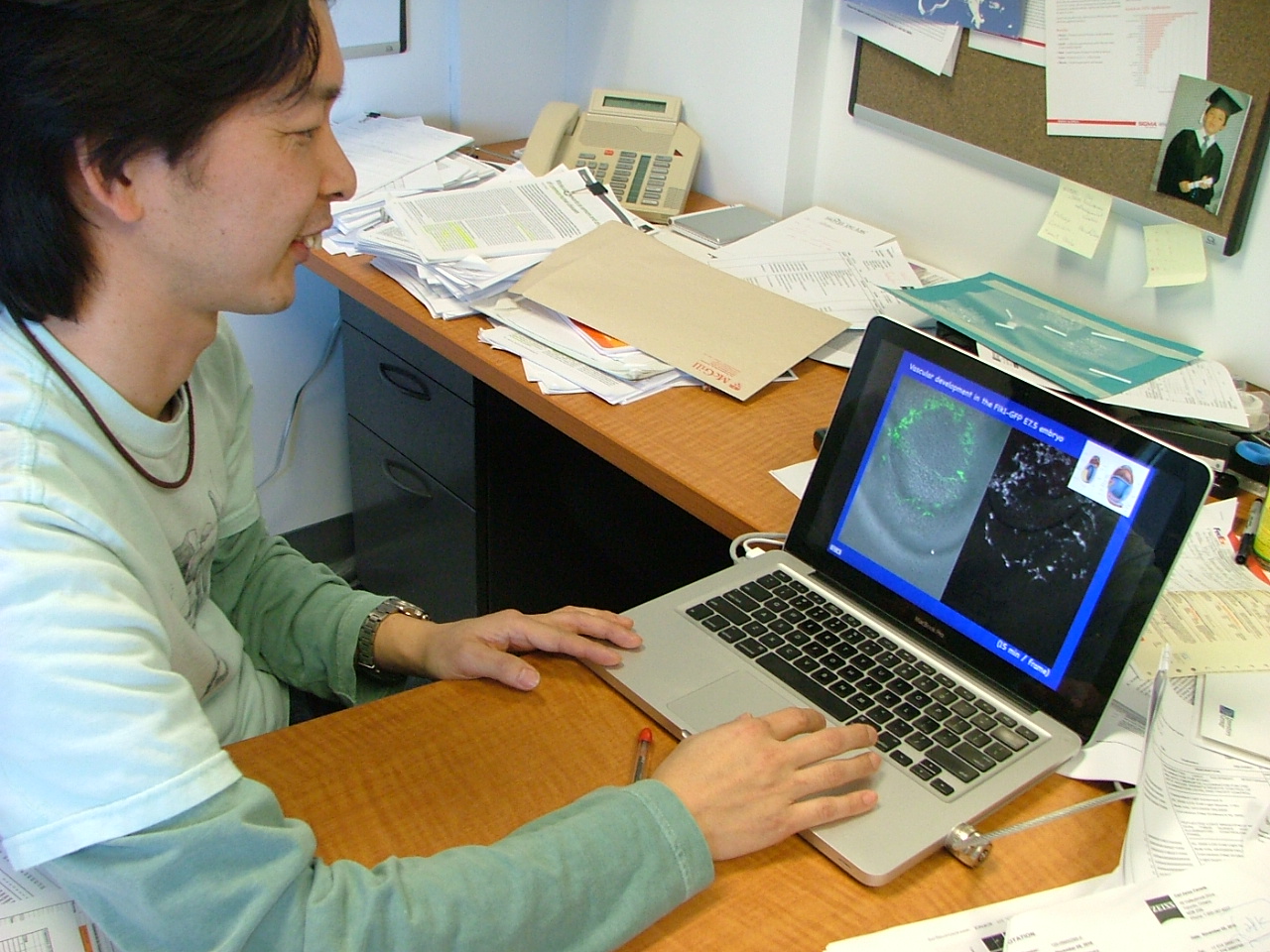

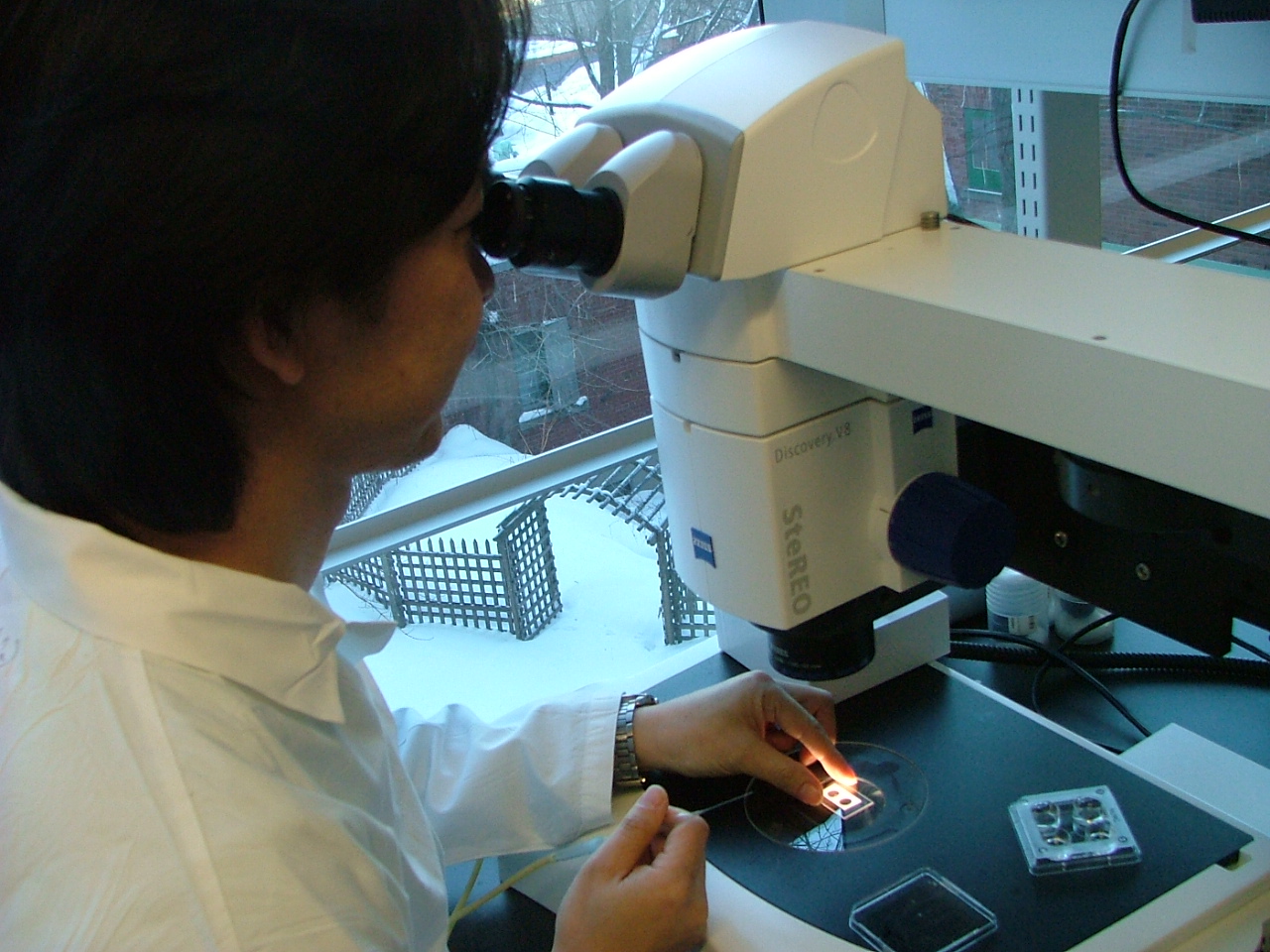

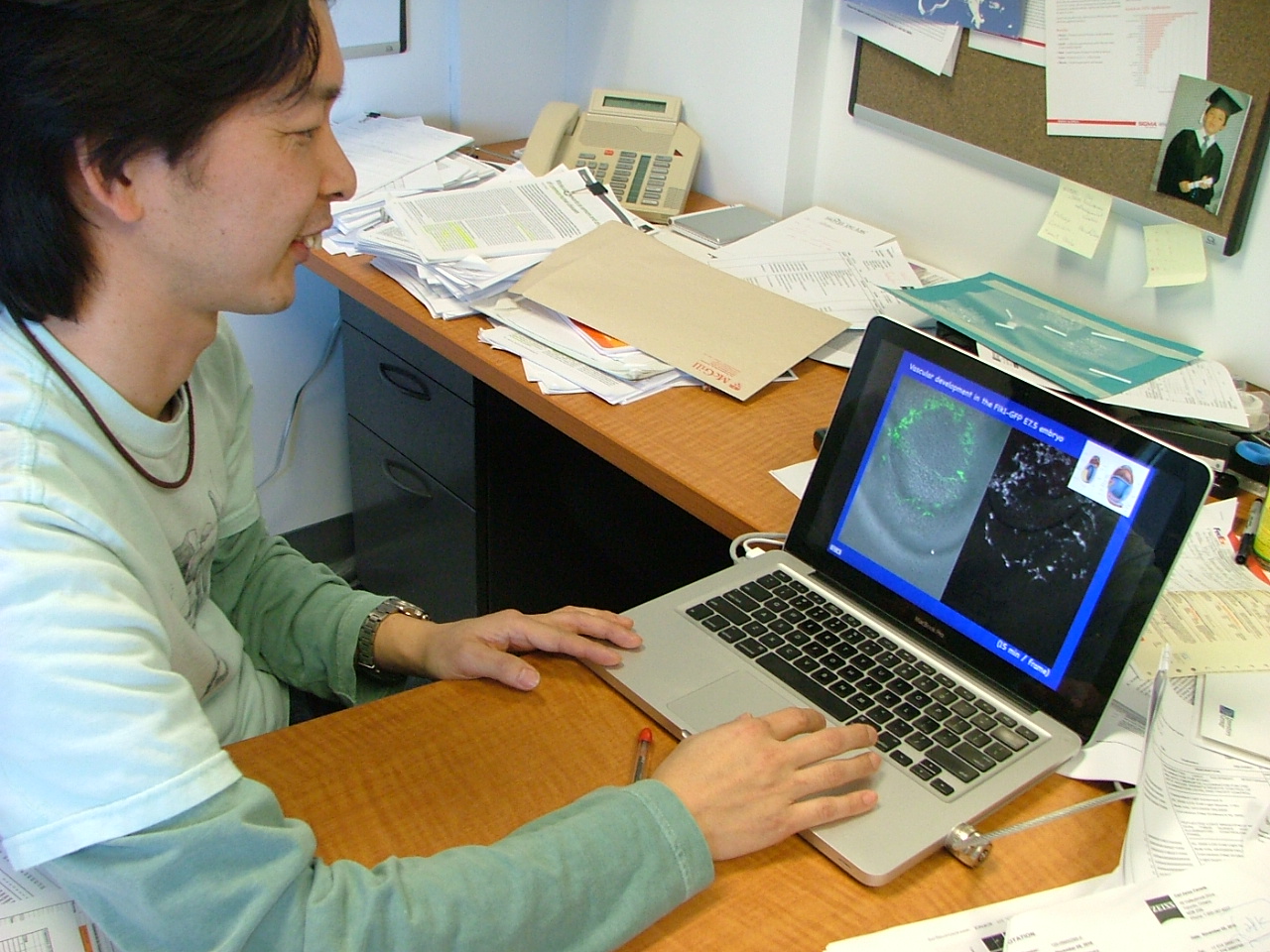

Yamanaka chose Developmental Biology as a career and cultivated innovative techniques and equipment that enabled him to study embryos through a microscope outside the womb. He even visits hospitals demonstrating the potential of his inventive work. “Developmental Biology is something dynamic and fundamental,” says Yamanaka. “I can see changes in the embryo through a microscope with my eyes.”

So what does that direct observation yield, beyond a continued source of fascination for the Assistant Professor at McGill’s Department of Human Genetics? “Understanding dynamic cellular behavior in vivo provides useful insight into various diseases, including cancer. It also provides fundamental knowledge for stem cell research and regenerative medicine,” explains Yamanaka.

Research in developmental biology examines the processes of cell growth and differentiation – the process in which a stem cell matures and becomes a definitive cell type, such as a nerve or blood cell. A major area of study in stem cell science is learning the triggers that cause differentiation.

“Recent discovery by Dr. Shinya Yamanaka [no relation] of Kyoto University shows that definitive cell types in our body can revert back to pluripotent stem cells, which are equivalent to one of the first three cell types in the embryo,” explains Yamanaka. “This opens up various possibilities in medicine, such as drug screening, disease modeling and cell and gene therapy treatment.”

Working out of the Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre at McGill, Yamanaka has been fervently following up on these possibilities by studying the very early stages of mammalian development. Now, the Canadian Institutes of Health and Research (CIHR) has awarded him a $750,000 grant for further research into cell polarity and generation of the first distinct lineages in the mouse embryo. He aims to generate a deeper understanding of cell behaviour that could eventually lead to treatments for debilitating diseases. “I am very relieved and pleased,” says Yamanaka. “I can do nothing without grants – it’s not easy for young new researchers in the current tight economy.”

With the newly acquired funds, Yamanaka and his research team will now be able to use the state-of-the-art microscopic techniques that he developed to analyze the process of cell polarity formation in the embryo. “We will perturb cell polarity by various ways and analyze its effects,” explains Yamanaka. “Our research will provide insight into the molecular machinery of pluripotency in a cell.”

Isolated human embryonic stem cells are pluripotent, meaning they can generate any cell in the body except for the placenta. “The embryonic stage we work with, the pre-implantation stage, is when the separation of cells for the placenta and cells for the fetus occurs and is a very unique process to mammals,” continues Yamanaka.

Looking back on his career path, Yamanaka vividly remembers the day he found a new gene – this time studying an aquatic species. “After long and painful experiments – just imagine searching for a small speck of diamond in a sandbox – we found a new gene that could induce a secondary head in the embryo of a zebrafish,” recalls Yamanaka. The discovery addressed one of the major issues in developmental biology at the time – how the fertilized egg of a vertebrate establishes the body axis. “That day, I learned the gene we identified was novel from its sequence,” adds Yamanaka. “That was the moment I strongly felt that I was doing something totally new and nobody in the world knows what I see.”

Yamanaka wants other young researchers to have that awe-inspiring experience – and enthusiastically welcomes motivated graduate students into his team. “Canada has a strong history in the fields of human genetics and stem cell biology,” he says. “Other than canoe camping, that is one of the reasons I chose to stay in this country.” So far, being here has enabled Yamanaka to fulfill his quest to question and participate in biology – not bad for a boy who started off wanting to be simply the keeper of the natural world’s creatures.

—

Yojiro Yamanaka, PhD, Assistant Professor of Human Genetics at McGill University, has been awarded a $750, 000 grant by the CIHR to study embryonic development at McGill’s Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre. “I hope our study will shed light on the principal of mammalian development,” says Yamanaka.

–

When Yojiro Yamanaka was a child growing up in Japan, he wanted to be a zookeeper. But his general interest in the biology of the natural world eventually led him to discover scientific knowledge based on other people’s experiments. “I realized that I did not need to just understand and memorize, but I could question and participate. Since then, I followed have my curiosity.”

However, after graduate studies in Pharmaceutical Sciences and a PhD in immunology, round cells in test-tubes failed to peak that curiosity. Something was still missing – and it turned out to be the ability to directly observe the development of life on a cellular level.

Yamanaka chose Developmental Biology as a career and cultivated innovative techniques and equipment that enabled him to study embryos through a microscope outside the womb. He even visits hospitals demonstrating the potential of his inventive work. “Developmental Biology is something dynamic and fundamental,” says Yamanaka. “I can see changes in the embryo through a microscope with my eyes.”

So what does that direct observation yield, beyond a continued source of fascination for the Assistant Professor at McGill’s Department of Human Genetics? “Understanding dynamic cellular behavior in vivo provides useful insight into various diseases, including cancer. It also provides fundamental knowledge for stem cell research and regenerative medicine,” explains Yamanaka.

Research in developmental biology examines the processes of cell growth and differentiation – the process in which a stem cell matures and becomes a definitive cell type, such as a nerve or blood cell. A major area of study in stem cell science is learning the triggers that cause differentiation.

“Recent discovery by Dr. Shinya Yamanaka [no relation] of Kyoto University shows that definitive cell types in our body can revert back to pluripotent stem cells, which are equivalent to one of the first three cell types in the embryo,” explains Yamanaka. “This opens up various possibilities in medicine, such as drug screening, disease modeling and cell and gene therapy treatment.”

Working out of the Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre at McGill, Yamanaka has been fervently following up on these possibilities by studying the very early stages of mammalian development. Now, the Canadian Institutes of Health and Research (CIHR) has awarded him a $750,000 grant for further research into cell polarity and generation of the first distinct lineages in the mouse embryo. He aims to generate a deeper understanding of cell behaviour that could eventually lead to treatments for debilitating diseases. “I am very relieved and pleased,” says Yamanaka. “I can do nothing without grants – it’s not easy for young new researchers in the current tight economy.”

With the newly acquired funds, Yamanaka and his research team will now be able to use the state-of-the-art microscopic techniques that he developed to analyze the process of cell polarity formation in the embryo. “We will perturb cell polarity by various ways and analyze its effects,” explains Yamanaka. “Our research will provide insight into the molecular machinery of pluripotency in a cell.”

Isolated human embryonic stem cells are pluripotent, meaning they can generate any cell in the body except for the placenta. “The embryonic stage we work with, the pre-implantation stage, is when the separation of cells for the placenta and cells for the fetus occurs and is a very unique process to mammals,” continues Yamanaka.

Looking back on his career path, Yamanaka vividly remembers the day he found a new gene – this time studying an aquatic species. “After long and painful experiments – just imagine searching for a small speck of diamond in a sandbox – we found a new gene that could induce a secondary head in the embryo of a zebrafish,” recalls Yamanaka. The discovery addressed one of the major issues in developmental biology at the time – how the fertilized egg of a vertebrate establishes the body axis. “That day, I learned the gene we identified was novel from its sequence,” adds Yamanaka. “That was the moment I strongly felt that I was doing something totally new and nobody in the world knows what I see.”

Yamanaka wants other young researchers to have that awe-inspiring experience – and enthusiastically welcomes motivated graduate students into his team. “Canada has a strong history in the fields of human genetics and stem cell biology,” he says. “Other than canoe camping, that is one of the reasons I chose to stay in this country.” So far, being here has enabled Yamanaka to fulfill his quest to question and participate in biology – not bad for a boy who started off wanting to be simply the keeper of the natural world’s creatures.

—