By Gillian Woodford

In 1965, a young immunology researcher named Phil Gold, along with his PhD supervisor Samuel Freedman, achieved what was widely dismissed as a pipe dream at the time: they discovered the world’s first cancer biomarker. The discovery of the protein carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in patients with bowel cancer led to the world’s first blood test to detect and monitor cancer cells. Later found in 70% of all cancer tumours, CEA changed cancer research and treatment forever.

What many may not know is that, fresh from his CEA victory, Dr. Gold was asked to represent McGill at Expo 67. Montreal’s late entry into the World’s Fair was also dismissed as an impossible feat – and again the detractors were proved wrong. To this day it is one of the most successful ever held and cemented the city’s international reputation. Still a medical resident at the time, Dr. Gold took part in the conception of Man and his Health, an enormously popular pavilion whose surgical gore and guts thrilled visitors.

Creating awareness about medicine

“I showed them CEA,” recalls the affable immunologist and raconteur, who at 80 continues to teach medicine and see patients. The 1960s was a particularly exciting time for medicine, he says. “We had gone from the horse and buggy into the genetics age,” says Dr. Gold. “There was the idea we’re going forward into a whole new era with the understanding of how your cells work, how your genes turn things on and off, and be able to analyse the changes in the genome and lead us to better medicine.”

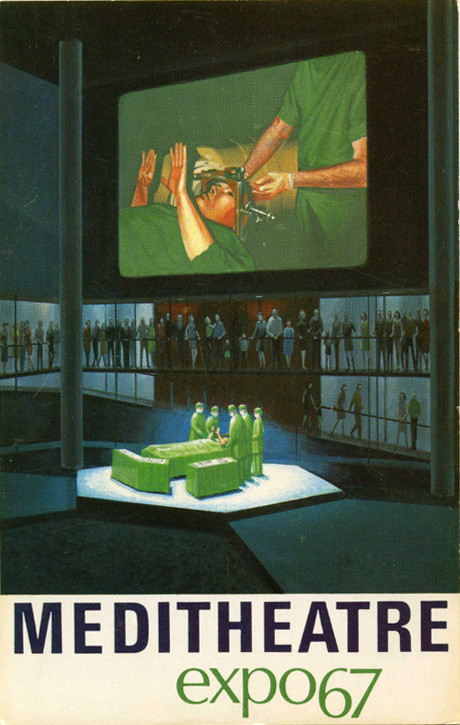

The pavilion’s aim was to initiate the public into this brave new world, in its unique multi-media space. “The thing that really sold Man and his Health was the architecture of the building,” says Dr. Gold. “It was superb.” The pavilion, a low hexagonal building made up of tiered timbers, was centred around the dimly lit Meditheatre. On six stages actors simulated medical procedures while three giant screens showed footage of real medical procedures as well as interviews with physicians. There were also five exhibition halls, one of which featured Dr. Gold’s CEA presentation.

Dr. Gold says another important aim of Man and his Health was to humanize the rapidly specializing medical profession. “Even in the 60s, only 20% of the medical population were specialists. The rest were family doctors. Then we flipped it and it got sort of weird,” says Dr. Gold. “The idea was that people could relate to their family physician. But when they went to see a specialist it was kind of a cold and transient phenomenon. And that wasn’t true, it was the perception.”

A big part of Man and His Health was to change that perception,

says Dr. Gold. And it worked. “Talking to people as they came out, they said they had a warm feeling about medicine they hadn’t had before. Surgeons weren’t only hiding behind their masks. They cared about their patients.” The pavilion’s design helped reinforce this perception, says Dr. Gold. “The theatre had this feeling of being hugged because you were surrounded by medicine.”

Some members of the audience, however, felt more horrified than hugged.

“They had St John’s Ambulance people because people were passing out as blood was flowing off the screen,” Dr. Gold recalls. Real footage of an open-heart surgery on a ‘blue baby’ and a Caesarean section proved too much for numerous people who fainted in the Meditheatre each day.

Man and his Health had a public health promotion aspect as well. “We talked about a lot of things, like how cigarettes aren’t good for you, we can do things to detect cancer early, antibiotics are now available for so many things.” Dr. Gold, a healthy lifestyle crusader, admits with glee that he continues to make a nuisance of himself on campus with his anti-smoking fervour. “When they see me, they say ‘quick put out your cigarette, he’s coming!’”

The evolution of cancer treatment

Dr. Gold is extremely proud of CEA, which is principally used to monitor cancer recurrence after surgery, but ironically is eagerly awaiting its demise. “My great distress about CEA is that I thought it would be long gone by now and that there would be far better tests that would replace it entirely,” he says. “Hell, this was 1965 – it was primitive.” He is glad to report that it is now possible to attack CEA and other antigens, using a method called Immune Checkpoint Blockade. “Turn off the turn off against cancer,” is how Dr. Gold describes it, saying this approach has already drastically improved survival in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer.

For Dr Gold the thrill of his CEA eureka moment is as fresh today as it was 52 years ago. He regularly shares that moment with his students:

I had taken this gel home and filled it with materials that I needed to look at – it’s called an antigenic band – and put it somewhere where the kids couldn’t get at it. It was Friday evening. I said to my wife, “Tomorrow morning, dear, we’ll look at it.” The next morning came along and she said, “Let’s have a look.” I said, “No, let’s have coffee first. Just in case it doesn’t turn out.” So we had coffee, and she said “Now?” “Ok, now,” I said. And there it was. There were the bands.

And I say to the students, I don’t know if you know why you do research, but I found out that day why I do research. Because for a whole weekend, I knew something that no one else in the world knew. And that was a remarkable feeling. And then on Monday I went and told anyone who would listen!

July 19, 2017