October is Occupational Therapy Month so we take this opportunity to look at the history of Occupational Therapy at McGill University in this month’s instalment of our series highlighting the Faculty of Medicine’s contribution to the city of Montreal in honour of its 375th birthday.

Occupational therapy (OT) can trace its origins to the 18th century, when the desperate crusade to free mentally ill patients from their shackles led to the gradual reform of the insane asylums. Early reformers engaged with patients rather than treating them like pariahs, got them outdoors and encouraged them to take up useful occupations like needlework and gardening.

During the First and Second World Wars OT rapidly developed into the discipline we know today. Early OTs – often referred to as reconstruction aides in the military context – ministered to wounded soldiers suffering from shell shock as well as physical injuries. They offered them activities and helped them regain their day-to-day autonomy by re-learning to bathe and dress themselves — what OT’s now call Activities of Daily Living (ADL).

Occupational therapy came to McGill University after WWII. Initially, the School of Physiotherapy (PT) was established in 1943, the first in Canada to be part of a Faculty of Medicine. In 1950, occupational therapy was introduced in a three-year diploma program combining physical and occupational therapy. The following year the School was renamed the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy (SPOT). Over time these professional programs evolved to our current version of SPOT, which offers two separate (OT and PT) entry level professional Master’s programs.

In the early days, the program had a purely clinical and professional focus. “Students in the early program came straight out of Grade 11,” recalls Dr. Beverlea Tallant, who

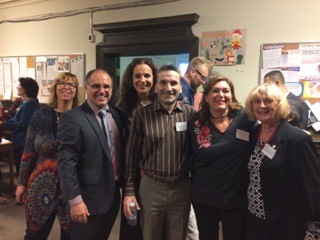

From left to right: Nadine Larivière, now Director of OT at Université de Sherbrooke; Aliki Thomas, now Assistant Professor, Occupational Therapy program at McGill; Mario Côté; Salvatore Chine; Anat Lazar; Beverlea Tallant.

graduated from the University of Toronto in 1961 and joined the McGill OT faculty in 1969. “Some of these students were only 17 [years of age] and found interacting with psychiatric patients and individuals with physical disabilities a real shock.”

The faculty had two requirements at the time, says Dr. Tallant: “To be a good teacher, particularly with clinical expertise, and to be active at a senior level in our professional associations.” The emphasis on research came later. “As faculty, we evolved to become a typical academic program at McGill,” she adds. A Bachelor’s degree in OT was introduced in 1971 and an MSc in Rehabilitation Science was added a year later. In 1988, McGill became the first university in North America to offer a PhD in Rehabilitation Science. “We actually coined the term at McGill”. During these changes, many of the OT and PT faculty, including Dr. Tallant, acquired graduate degrees while teaching and maintaining their professional association obligations. “I can assure you that working full time and doing all this was a big job, but everyone loved the School and what they were doing.”

Dr. Tallant recalls the heady days when Medicare was being brought into Quebec and Claude Castonguay was holding hearings to decide what professional services would be covered. Dr. Tallant met him at a lecture and ventured to ask whether the Quebec Society of OT (QSOT) had submitted a brief. He replied “No”, and so she alerted the Director of OT at the time, Joyce Field, who along with colleagues from the QSOT, McGill, and the Université de Montréal, set to work to make the case for their profession. But they hit a snag. “The Castonguay Commission decided OTs should report to PTs who should report to physiatrists,” says Dr. Tallant. “Of course, we OTs were appalled because as far as we were concerned OTs and PTs were on the same level. The thing that saved us was that, as OTs, worked in mental health, the psychiatrists said ‘Sorry, we won’t be receiving information from OTs about our patients via a physiatrist.'” The OTs persevered and OT was officially recognized as a distinct health care profession.

Over the years, McGill’s OT program has been a leader in many areas of OT research, including dysphagia and the development of an assessment and feeding clinic at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, driving rehabilitation and simulated power wheelchair training, says Dr. Tallant. Several assessments have been developed by OT researchers such as the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) (now translated into over 60 languages) which measures functional abilities in ADL for individuals with cognitive impairment. The McGill Ingestive Skills Assessment has also been an important tool for assessing swallowing issues in the elderly for many years. “We were one of the originators of driving rehabilitation,” she adds, noting that retaining the ability and right to drive after an illness or in old age is an issue that is on the rise. In 2016, SPOT celebrated the 10 year anniversary of the online graduate certificate in Driving Rehabilitation created for OTs who would like to specialize in the field.

Currently, OT faculty are actively involved in research on children with brain based disabilities, virtual reality as a treatment modality for motor impaired individuals, understanding the phenomenology of the client’s experience of their psychiatric condition, environmental barriers for community participation by the physically challenged, homelessness, and knowledge translation projects for clinical OT practitioners and/or client caregivers.

More information about current OT research can be found here.

October 27, 2017