Higher rates of skin cancer affecting those living in southern and coastal areas of Canada

Rates of melanoma, a deadly form of skin cancer, are on the rise in Canada. Those living in southern and coastal areas are most at risk, according to a new study led by McGill University.

“Cutaneous melanoma causes more deaths than any other skin cancer, accounting for 1.9 per cent of all cancer deaths in men and 1.2 per cent in women in Canada. Globally, there were 290,000 new cases of this form of skin cancer in 2018,” says Dr. Ivan Litvinov, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at McGill University.

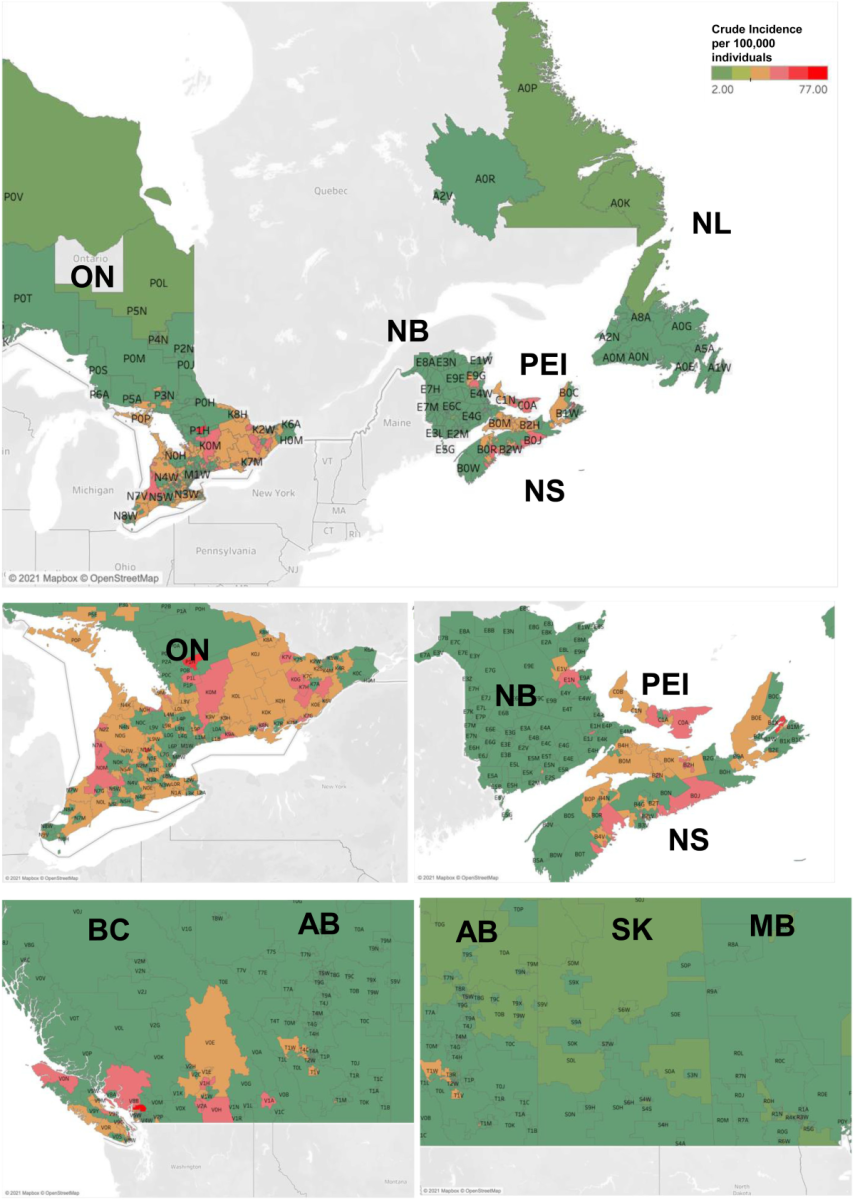

In Canada, Maritime provinces of Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia had the highest incidence rate of melanoma in the country, even after adjusting for other factors such as age. Rates in New Brunswick, Ontario, and British Columbia were also high but comparable to the national average of 20.75 cases per 100,000 people per year, while the prairies provinces and Newfoundland and Labrador had lower rates than the Canadian average. “Melanoma incidence is not uniform across Canada and there are some pockets of the country that are affected much more than the others,” says Dr. Litvinov.

Skin cancer rate higher among men and older adults

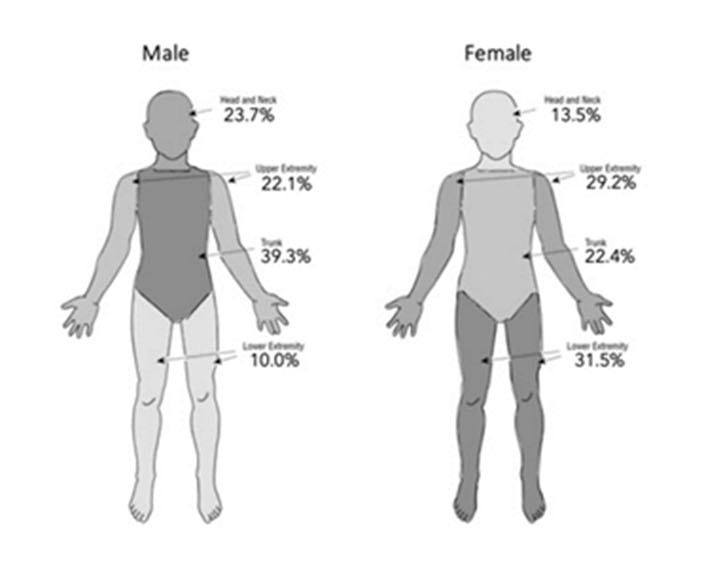

The researchers published their results in the journal Frontiers in Medicine and found that incidences of melanoma were higher in men than in women – around 54 percent versus 46 percent respectively, with the exception of melanomas that often happen on fingers (acral lentiginous melanoma). “This is possibly due to higher exposure to ultraviolet radiation in nail salons,” says Dr. Litvinov. For men, skin cancer was more common on the trunk and in the head and neck areas. For women, it was more common in the legs and arms.

Rates of melanoma were also higher in people over the age of 60. “Skin cancer risks increase as you age, likely due to accumulated exposure to ultraviolet radiation from sunlight or other artificial sources. But skin cancers may also be found in younger people. Factors like genetics, personal history, where you live, all play into the risk of exposure. Sometimes melanoma can happen in a sixty-year-old due to sunburns that they had in their teens, twenties, and thirties,” says Dr. Litvinov.

Mortality rates are decreasing in Canada

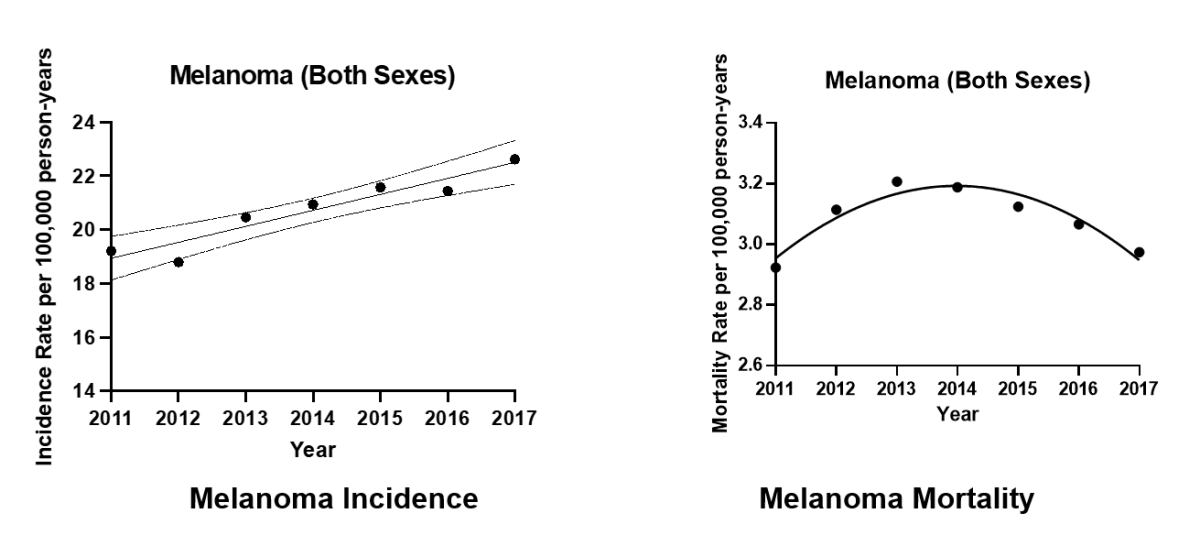

The researchers note that although melanoma rates are increasing, mortality rates are decreasing for the first time since 2013. This is likely due to new, targeted immunotherapy treatments, they say. Still, the international picture remains more uncertain.

“Globally there was a 44 per cent increase in melanoma rates over the years, with a corresponding surge in mortality rates of 32 per cent. Rates of melanoma are likely to increase with climate change and the thinning of the Earth’s ozone layer,” says Dr. Litvinov.

According to the researchers, public education campaigns that target people living in high-risk geographic areas are essential in preventing melanoma. These campaigns should also target men and women differently. “We need to encourage women to protect their legs and arms from the sun, while for men sun exposure on the torso, head and neck is the main problem,” says Dr. Litvinov.

| About this study

“Population-Based Study Detailing Cutaneous Melanoma Incidence and Mortality Trends in Canada” by Santina Conte, Feras Ghazawi, Michelle Le, Hacene Nedjar, Akram Alakel, François Lagacé, Ilya Mukovozov, Janelle Cyr, Ahmed Mourad, Wilson Miller Jr., Joël Claveau, Thomas Salopek, Elena Netchiporouk, Robert Gniadecki, Denis Sasseville, Elham Rahme, and Ivan Litvinov was published in Frontiers in Medicine. |