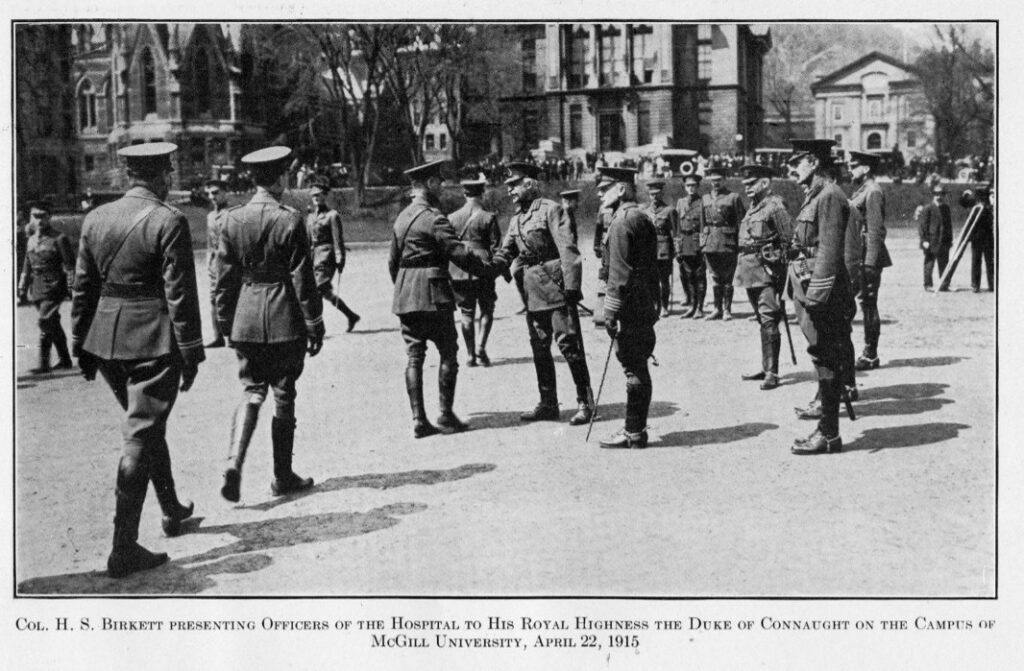

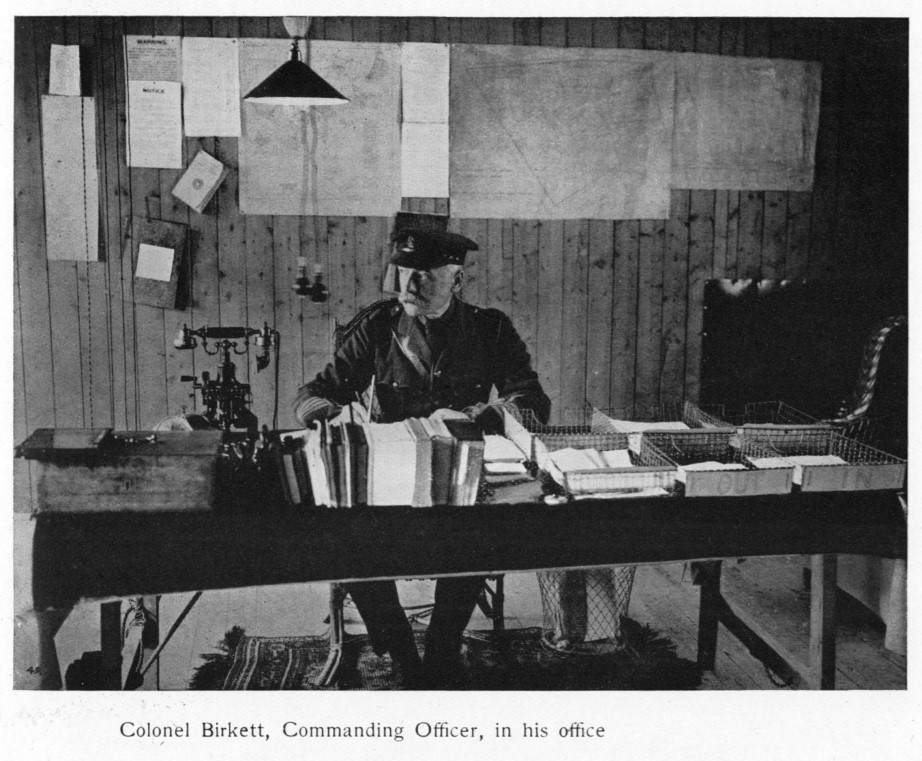

The 3rd Canadian General Hospital (McGill) was the first military hospital to be mounted and run by a university Faculty of Medicine during the First World War. Initiated by McGill University’s Dean of Medicine (1914-1921), Herbert Stanley Birkett, the hospital accepted its first patients on the French coast about 40 miles from the front in August 1915. From then until it closed in 1919, the hospital admitted 143,762 patients and performed 11,395 surgeries.

“It was the premier hospital of the Allied Forces,” says Lt-Col Andrew Beckett. Lt-Col Beckett, member of the Royal Canadian

Medical Services, Assistant Professor of Surgery at McGill, and Montreal General Hospital trauma surgeon, and Dr. Edward J. Harvey, Professor of Surgery at McGill and orthopedic trauma surgeon at the Montreal General Hospital, recently wrote a remembrance of the unit, “No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill) in the Great War: service and sacrifice,” published in the Canadian Journal of Surgery.

“Because of its strong links to the US, particularly Johns Hopkins due to the affiliation with Sir William Osler, McGill really had an edge,” notes Lt-Col Beckett. “The British Forces were not as advanced in some ways as the No. 3 McGill hospital was. It became the informal meeting place for the medical elite with a lot of VIP visits all the time.” There was also valuable research and innovation, he says, most significantly in advances in the use of blood transfusions, a relatively new practice that prevented countless injured soldiers from succumbing to shock.

Dr. Birkett staffed his hospital with doctors and nurses from McGill and its two big teaching hospitals, the Montreal General and the Royal Victoria. They included Chair of Pathology, George Adami; Edward Archibald, a thoracic surgeon and Canada’s first neurosurgeon, who pioneered at No. 3 the use of citrate as an anticoagulant to facilitate transfusions; Francis Scrimger, a surgeon who would earn the Victoria Cross for bravery; Clare Gass, a nursing sister whose war diary offers enormous insight into the day-to-day life at the hospital; and most famously John McCrae, physician and author of “In Flanders Fields.”

To Hades and back

Dr. McCrae, a veteran of the Boer War, enlisted shortly after war was declared and headed to Europe in September 1914, with a plan to join the McGill medical contingent when it arrived. In the spring of 1915, Dr. McCrae took part in the Second Battle of Ypres, in which the German forces launched the world’s first large-scale poison gas attack. “Seventeen days of Hades!” was how Dr. McCrae described the experience to his mother.

After Ypres, as planned, Dr. McCrae transferred to the new McGill hospital as its Officer in Charge of Medicine. He wrote to his mother expressing his mixed feelings about leaving his comrades on the front: “I am sorry to leave them in such a hot corner, but cannot choose and must obey orders. It is a great relief from strain, I must admit, to be out, but I could wish that they all were.”

By all accounts, Ypres changed him forever. The man whom his friend and fellow writer Stephen Leacock said was “in great demand at Montreal dinner parties”[1] was now bitter and disillusioned. His friend Dr. Archibald “was busy trying to match-make McCrae with any one of the nurses and he would report progress on this to his wife back in Montreal,” says historian Dr. Susan Mann, editor of Clare Gass’s war diary. He had his work cut out for him, she says. “Archibald wrote that McCrae could be rather stiff and domineering and that the nurses didn’t like him.”

There is a claim – possibly apocryphal – that Dr. McCrae and Clare Gass were friends and that he showed her “In Flanders Fields,” which had been rejected by The Spectator, and she encouraged him to send it to Punch. Dr. Mann has her doubts. “I don’t think there was a relationship at all,” she says. “She may have known him as a teacher and as a doctor but there’s a very hierarchical system. The only connection that can be deduced is that she put his poem in her diary six weeks before it appears in Punch in December 1915,” says Dr. Mann. “But it’s also in [fellow nurse] Sophie Hoerner’s papers and it’s in Archibald’s letter before it appeared in Punch. So it may have done the rounds.”

Before World War I, the nursing contingent of the Canadian military was tiny. Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald had served in the Boer War with Dr. McCrae, but most of the young nurses who were part of the initial recruitment for the No. 3 Canadian General had no military experience. Also, unique among their peers, the Canadian nurses were part of the military hierarchy and had ranks just like the men, which meant they had people above them and below them. This arrangement meant the nurses could focus more than ever on nursing – which was still a relatively young profession – because many of their non-nursing duties were for the first time taken care of by others.

That said, some of the younger lower-ranked men, often medical students who had been recruited as stretcher bearers or orderlies, balked at having to take orders from women. Lt-Col. Beckett and Dr. Harvey note that, “As typical medical students, they were keen to work with the staff surgeons of the hospital and often tried to get away from scut work on wards. Often they would remove themselves from their ward duties, much to the dislike of the nursing staff, such as Clare Gass, to observe procedures in the operating room.” Dr. Mann adds that the nurses’ authority and rank had to reiterated again and again by the commanding officers.

Dr. McCrae contracted pneumonia and died January 1918 after having been named the first Canadian consulting physician to the British Army. Clare Gass survived the war but left nursing. Upon her return to Montreal she chose to study in the new field of social work at McGill and worked as a medical social worker in Montreal until her retirement in the 1950s.

To read “No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (McGill) in the Great War: service and sacrifice,” published online ahead of print December 1 2017 in the Canadian Journal of Surgery, by Lt-Col Andrew Beckett and Dr. Edward J. Harvey, please visit: https://canjsurg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/60-6-012717.pdf

[1] “Col. McCrae’s vision of the poppies,” Stephen Leacock, The Times (London), 11 November, 1921

Related coverage

Reader’s digest | Who was John McCrae, writer of “In Flanders Fields”?

November 29, 2017