This article was originally published on The Conversation, an independent and nonprofit source of news, analysis and commentary from academic experts. Disclosure information is available on the original site.

By Dr. Emeritus Robert Reford Professor and Professor of Medicine at McGill, McGill University

The 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights paved the way for the study and publication in Canada of the Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in 1970.

Forty-eight years later, however, progress has been limited, with overwhelming barriers still in place that prevent our most talented to thrive in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

With this year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine slated to be announced soon, it’s well-known that barriers for women in science remain in place and are nothing new.

The late Dr. Maude Abbott is known for overcoming “the gender-based odds against her to become an internationally respected pathologist and a world authority on heart defects,” according to the posthumous acknowledgement on her Canadian commemorative stamp.

She’s also honoured with a Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque and was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame. But there’s been no scientific recognition so far of Abbott’s astonishing discoveries that founded the field of pediatric cardiology.

Abbott’s career overlapped Frederick Banting’s. As the discoverer of insulin and Canada’s only Nobel Prize in Medicine recipient, Banting’s surgical expertise enabled insulin extraction from what are known as the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, and alleviated Type 1 diabetes in dogs. This scientific discovery, applied to humans, is celebrated as one of Canada’s greatest medical gifts to the world.

Found a common developmental defect

Just as Banting’s were, Abbott’s scientific discoveries were applied to surgery. Her laboratory was a collection of autopsy specimens that she carefully curated and meticulously documented. Remarkably, she found in 92 autopsy cases a similar developmental defect, namely a shunt closure failure between the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Abbott advocated the use of surgery to correct this anomaly. In 1936, she compiled her “magnum opus,” entitled Atlas of Congenital Disease, which included a study of more than 1,000 other cases of congenital heart disease.

In 1939, two American physicians, Robert Gross and John Hubbard, reported the use of corrective surgery based on Abbott’s findings. They described the dramatic recovery of a seven-year-old girl with symptoms of cardiac hypertrophy characteristic of Abbott’s anomaly discovery.

Already outlined by Abbott in 1913, they used surgery to tie off the inappropriate connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery, enabling the child to fully recover. Their publication describing the surgery is highlighted today in the Journal of the American Medical Association as a “landmark article.”

A further life-saving discovery followed. Abbott was among the first to document the four congenital malformation characteristics of hearts from cyanotic “blue” patients. Named after the physician, Dr. Arthur Fallot, who defined the malformation in 1888, the disorder is known today as the “tetralogy of Fallot.”

An artificial shunt

An American physician extensively following Abbott’s work, Dr. Helen Taussig, recognized the important link between the Canadian doctor’s scientific discoveries and the success of Gross and Hubbard’s corrective surgery.

Taussig boldly hypothesized that an introduction of an artificial shunt to improve arterial oxygen supply could save the cyanotic “blue baby.” In 1944, Taussig and her surgical colleagues, Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas, successfully inserted the “Blalock, Taussig(and Thomas) shunt” in a 15-month-old baby. Sadly, this implementation of Taussig’s hypothesis and its treatment of cyanotic babies occurred after Maude Abbott’s death in 1940.

Abbott’s life-saving discoveries were developed as a direct result of being hired as an assistant curator at McGill University in 1898. Later put in charge of the McGill medical museum, her efforts as curator were heroic.

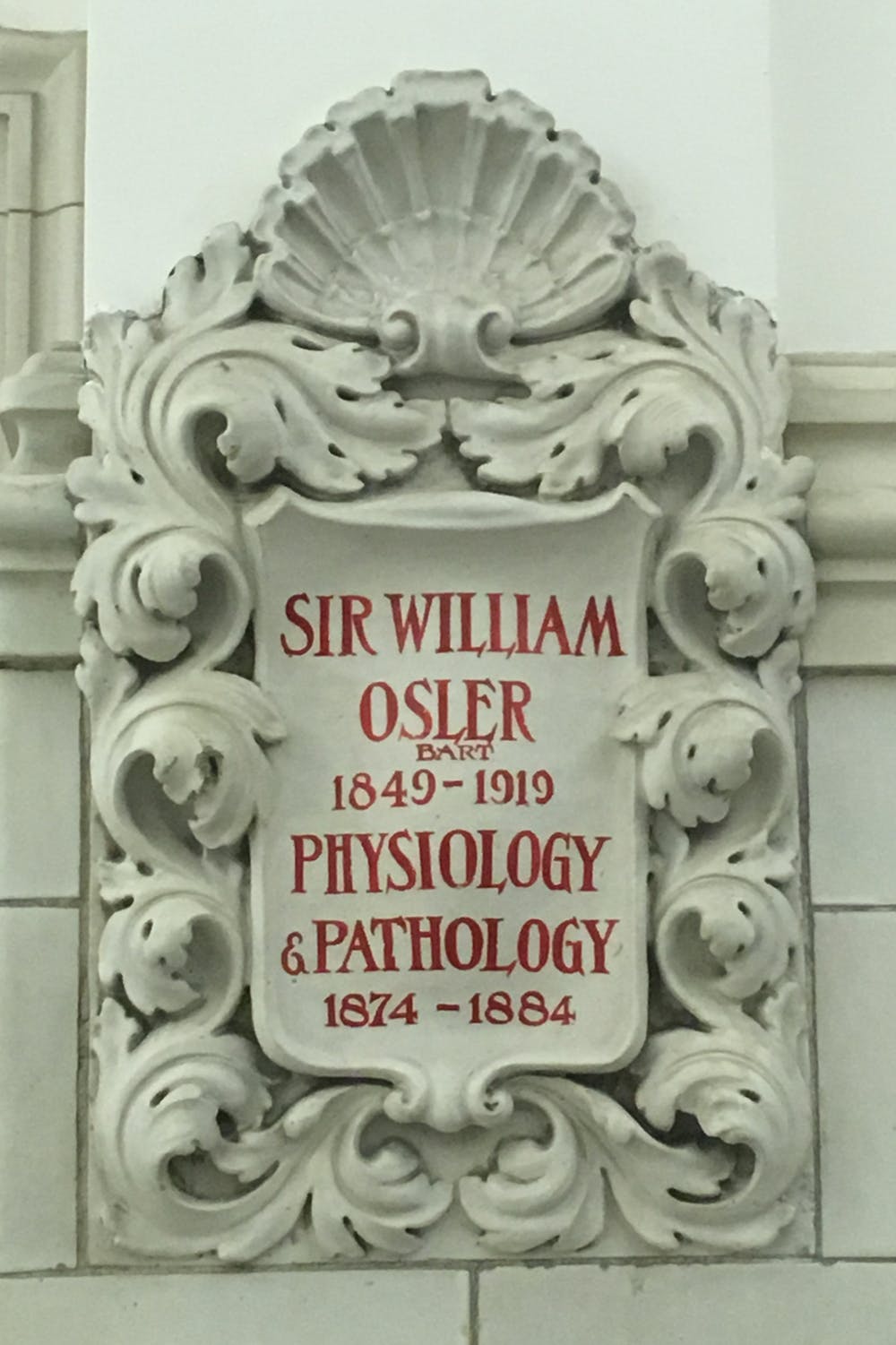

Abbott supported by Osler

Recognized and supported by her friend and mentor Sir William Osler, Abbott co-founded the International Association of Medical Museums in 1906, later becoming its first secretary in 1907. Her stunning pathology dissections are preserved today at the McGill Maude Abbott Medical Museum.

Abbott is the only Canadian and only woman depicted in Diego Rivera’s artistic mural celebrating the history of cardiology in the Institute for Cardiology in Mexico City. She is not only a founder of the field of paediatric cardiology, but also one of the premiere discovery researchers of her time.

It remains the dream for any life scientist to make a discovery that can save lives. Yet Abbott’s discoveries in the life sciences were never recognized by any scientific award in her lifetime. Scientific discoveries that have stood the test of time for more than 80 years deserve to be recognized.

Perhaps 78 years after her death, Abbott’s wish might be granted. It seems the least we can do.

John Bergeron gratefully acknowledges Kathleen Dickson as the co-author of this piece.

National Post | Maude Abbot: The Canadian scientist who deserved