Student-run program brings science education to Indigenous communities

By Eviatar Fields

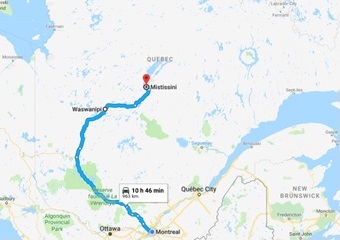

Run by graduate students in McGill University’s Integrated Program in Neuroscience (IPN), BrainReach North is a science education outreach program for remote indigenous communities in Quebec, which completed two outreach trips in May, one fly-in visit to the Inuit community of Kuujjuarapik and one road trip to visit schools in the Cree communities of Mistissini and Waswanipi.

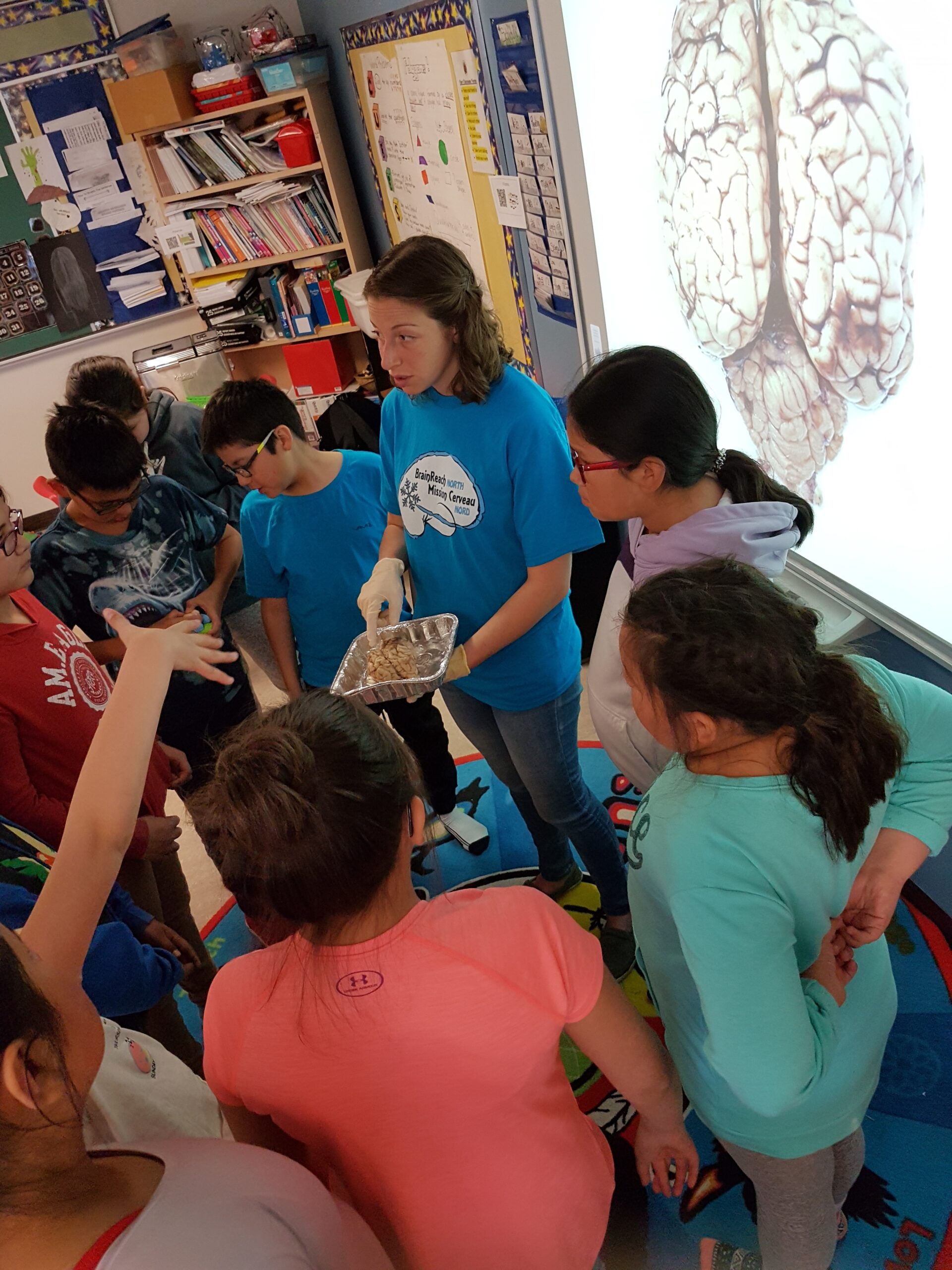

The primary goal of the initiative is to put a friendly face on brain science, providing students in the communities with an opportunity to ask questions about the brain or mental illness, while simultaneously providing graduate student volunteers with the opportunity to develop skills communicating science to the public. On each trip volunteers led hands-on brain-based science lessons for elementary and secondary students. Highlights included bringing a cow brain into the class and an electrophysiology setup that let people make each other’s muscles twitch by moving their own.

Two of the graduate student volunteers, Sébastien Belliveau and Eviatar Fields have written about their experience. The following is Eviatar’s story.

*********************************************

In May 2018, the McGill outreach program BrainReach North sent Roni Setton and myself on a road trip to northern Quebec to teach neuroscience to the Cree communities of Waswanipi and Mistissini.

Anyone peering into our car on that first day would have thought that we packed for a month-long camping trip, and in some ways we had. Aside from our personal belongings and several bags of teaching materials, we had brought our own sheets, blankets, pillows, towels and food. Lots of food. After some chatting and getting directions to the highway, I put on a podcast and Roni promptly fell asleep (I thought it was a really interesting podcast).

The drive was gorgeous: a slew of greens from the leafy bloom of different trees, with sporadic openings where crystal clear lakes, ponds and rivers filled the pockets between them. It seemed as though we were driving for eternity; there were no cars around on the two lane highway with the exception of those parked at campsites every few kilometres. Every so often we would see a sign warning that there would be “gas in 2 or 200” kilometres, which really emphasized how far away from home we were. Finally, after an 8-hour drive, we turned into Waswanipi, the southernmost Cree community in Quebec.

Our first impression of Waswanipi was that it bore a resemblance to any small rural town, but some differences became quickly apparent such as the fact that all street and

Courtesy of Roni Setton

building signs in the town were in both English and Cree. Although we had arrived in the evening, the town was bustling and lively. Young children were out playing and laughing along the streets. Older children were roaming around on scooters and bicycles in groups of two or three, and teenagers were rolling through on their ATVs. As we cruised slowly through the town, we spotted a few people waving to us from their windows, making us feel welcome while also reminding us that we stood out as strangers in the community.

After obtaining the keys to our lodging, we turned onto a dirt road and found our residence for the next two nights. It was a spacious and very cozy unit in a bungalow duplex complete with a full kitchen, living room, bathroom and two bedrooms, provided to us for our stay in Waswanipi by the school staff. We had been forewarned that the unit would be more or less bare, with the exception of furniture, which is why we brought the sheets, towels, pillows, etc. Luckily, the kitchen was stocked with cutlery and cooking utensils as we had forgotten to bring our own. After claiming our rooms we cooked ourselves dinner and called it an early night.

The next morning we arrived at Willie J. Happyjack Memorial High School at 8:40 a.m., ready for our first class. After a brief introduction to the vice principal, Nick Scopis, we were set up in a grade 8 class. At 8:50 a.m., the bell rang signifying the start of class and the students started slowly trickling in. Attendance during first period was not strong and the students were still waking up. Roni and I began with our discussion on the importance of the brain and the “Paper in the Pocket Challenge,” a simple activity to explain why the brain has wrinkles and grooves, but the students’ interest was not yet piqued. So, we pulled out the first trick up our sleeves: a cow brain, purchased from a butcher and preserved in formaldehyde provided by our friends at the Douglas Institute Brain Bank. Shocked, excited, and perhaps slightly put-off, the students crowded around the desk as Roni pointed to the different lobes and their respective purposes. When they returned to their seats, the students listened much more intently. This was our first lesson in what it means for science to be truly hands-on.

Our next topic was neural communication. After picking the students’ brains to gauge what they thought a brain cell would look like and how they communicated, we asked the class if they wanted us to prove that brain cells send electrical signals. Looking pretty skeptical, they agreed and gathered around the front of the class, were I was setting up a Human-to-Human Interface (HHI). The HHI is a commercially available teaching tool from Backyard Brains that captures the electrical current running through the ulnar nerve, amplifies it, and uses that current to light up a row of red lights which glow brighter the more I clench my fist. Even more impressive, the machine can then transfer the signal to a pair of electrodes placed on Roni’s arm and stimulate her muscles (painlessly, though maybe slightly uncomfortably), demonstrating that all that is needed to cause muscular contraction is electricity; we could bypass Roni’s conscious control of her arm by harnessing the electrical power of my own muscles.

Courtesy of Roni Setton

With the students surrounding me and my arm hooked up to the HHI, I described that when I decide to clench my fist, an electrical signal will be transferred from my brain cells though my brain stem into my spinal cord and through to the peripheral nerves that terminate on my arm muscles. With that, I proved to them that the stronger I clenched my fist, the more lights lit up because of the stronger signal. The students were rapt with attention now and recounted back to us how this was possible and the path the electrical signal would take from the brain to close my fist. Once we were sure they understood, I hooked Roni up to the machine and stimulated her arm, which was an even bigger hit. After again having them recount how this was possible, we asked who wanted to see their cells communicate and stimulate Roni’s arm and every hand in the class went up. We let two students try it out and then gave Roni a break.

Our next lesson dealt with the five senses, with a heavy emphasis on the way our brain interacts with our environments. This was a much denser section, dealing with the concept of photoreceptors and the areas responsible for each sense. We led the Paper Clip Activity, where Roni would touch an open paper clip to my forearm or hand and I, blindfolded, would have to guess if she used one or two prongs. This was meant to introduce the somatosensory homunculus and the varying size of receptive fields. We agreed after the lesson that this part of the day was too lecture-heavy and not nearly interactive enough. More than in most of the Montreal classrooms I’ve visited with BrainReach High-School, the students needed regular hands-on activities to stay engaged.

Finally, we got to the last section of our presentation: attention. We had two excellent activities prepared for this, the Monkey Business Illusion and the Stroop Task. The Monkey

Business Illusion tests the attention of the viewer, by having the viewer watch two teams pass a ball to each other with the instructions to count the number of passes that one team makes. Halfway through the video, a gorilla walks through the screen and beats its chest, designed to mask the other more subtle changes going on in the background. The kids were so proud of themselves when they counted the right number of passes made by the team wearing white and when they caught on to the gorilla, but the look of realization on the students’ faces when they realized that none of them noticed the curtain change colour or the player in black leaving the stage was priceless. The Stroop Task went even better; we displayed the letters of a colour (forming a word) and had the class yell out the colour of ink in which those letters were displayed (while ignoring the word itself). The whole class was roaring with laughter as they consistently read the word instead of yelling out the colour of the ink, and then catching themselves in their mistakes. I think we really got through to them here; they finally understood why texting in class or listening to their music during lessons led to poorer learning. We ended with a brief discussion on how to improve attention and the day was over.

Most of the classes over our two days in Waswanipi were similar. Some classes were more difficult to keep control over and some were quiet and reserved, but for the most part the classes were interactive and interested. The cow brain, the HHI, and the attention activities were easily our biggest hits. We taught six 50 minute classes each day, with a 50 minute lunch separating the morning and afternoon periods; both Roni and I came out of those two days with a newfound respect for our high school teachers. After a nice meeting with Nick the vice principal and some kind words and thank yous, Roni drove us another two and a half hours northeast to Mistissini, our second community.

Mistissini was larger than Waswanipi, about twice the size in population; our residence here was at the Auberge Mistissini Lodge, a four-star hotel that was quite cozy. The hotel was situated just on the outskirts of town, with our room overlooking the southern-most bay of Lake Mistissini. Settling in, we ate dinner, played a couple rounds of a card game, Spit, and went to sleep. We arose the next morning for our run, using that as an excuse to explore the town. Everyone was friendly, waving to us as we passed by and saying good morning. We ran to the beach and were followed by two gorgeous Huskies who ran into the water and then jumped around on us playfully, licking our faces and playing with each other. Once back, we headed to Adel’s Diner for a hearty breakfast of poached eggs, bacon and pancakes and then off to the day’s lessons at Voyageur Memorial Elementary School.

Courtesy of Roni Setton.

The vibe at Voyageur Memorial Elementary School was much different than at the Waswanipi school; being an elementary school there was much more energy and enthusiasm. We taught one full-sized class and two combined classes that were all around grades 5 and 6. The students were adorable and very dynamic, asking an endless stream of questions about graduate school, what we did in our labs, brain surgery and about the activities we did. They seemed very knowledgeable, answering every one of our questions exceptionally and even following up with some of their own. We could barely make it through the cow brain and HHI as they were so enthralled by what we were showing them. The vice principal, ReBecca Tolley, was very impressed, offering to put us in touch with the high-school next door so that we could come back the following year. We spent the rest of the day exploring the town, going for a hike in the woods surrounding it, and sitting on the beach.

The following day, it was finally time to return home to Montreal. We loaded up the car and began the 9-hour trek back south. This

Courtesy of Eviatar Fields

route was even more beautiful than our way north; it was a warm sunny day and we followed the beautiful Ashuapmushuan Wildlife Reserve and Saguenay River so we had a nice mixture of greens and blues the whole way. After a quick stop for groceries outside of Montreal, we headed home.

This trip was a wonderful experience. Both Roni and I agree that it opened our eyes to the world around us, allowing us to experience a culture that’s right next door but we didn’t know much about. This trip allowed us to view a world that we otherwise would not have had a chance to interact with, and to influence and motivate people that otherwise might not have a chance to explore hands-on science or think about the amazing things the brain does. Judging from the reaction of the majority of the kids, the teachers and the vice principals, we had a very positive effect. We hope that we opened doors and sparked curiosity in the students so that they might be able to pursue more in their classrooms and beyond.

There are a number of mentions that need be made, for without them this trip would never have been able to occur. First and foremost, an enormous thank you to Kelly Smart, the current director of BrainReach North, who organized everything from the contacts to lodgings to the car; without her, this trip would not even be a thought. A thank you to the executive BrainReach North team for helping to organize lessons and all the work you have done over the past year. A special thank you to McGill for sponsoring the trip and to the IPN for consistently supporting us. Finally, a special thank you to our contacts Nick Scopis and ReBecca Tolley, as well as to all of the teachers at Willie J. Happyjack Memorial High School and Voyageur Memorial Elementary School for making our stay nothing but warm and pleasant and our days at the schools smooth and easy, and to the communities as a whole for welcoming us in for a few days.

Read Sébastien Belliveau’s story | IPN students visit Quebec’s north – My voyage to Kuujjuarapik

June 20, 2018