Have you ever thought about what healthcare is like for people in remote regions of this geographically immense country? And how it might feel to be flown miles away from your home to get healthcare? Richard Budgell, an instructor in the Department of Family Medicine, gets his students to think deeply about such questions in his course, Inuit Health in the Canadian Context (FMED 527). This is the first course at McGill on Inuit health, and it is taught by an Inuk. I was keen to learn more, so I invited Richard for a chat to hear about his plans for this Winter term graduate course.

Have you ever thought about what healthcare is like for people in remote regions of this geographically immense country? And how it might feel to be flown miles away from your home to get healthcare? Richard Budgell, an instructor in the Department of Family Medicine, gets his students to think deeply about such questions in his course, Inuit Health in the Canadian Context (FMED 527). This is the first course at McGill on Inuit health, and it is taught by an Inuk. I was keen to learn more, so I invited Richard for a chat to hear about his plans for this Winter term graduate course.

Carolyn: I read in your course outline that the course “explores the histories, perspectives and contemporary realities of Inuit health in the four regions of Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit homeland), with a particular focus on the Nunavik region of northern Quebec.” How do you decide on the specific content to include in the course?

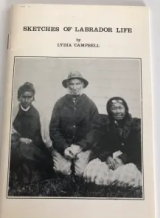

Richard: To the greatest extent possible, I include archaeological evidence and Inuit voices. Where I’m from, Labrador, there’s a tradition of literacy within the Inuit population that goes back more than 100 years. One of the sources that I use talking about the early encounters with Europeans is a journal that was written by Lydia Campbell, a great-great-great grandmother of mine. She is recognized as the earliest known published Inuk writer in Canada. Her journal was published in newspapers in the 1890s. So, wherever I can, I use first person accounts like that, where Inuit speak in their own voices.

Richard: To the greatest extent possible, I include archaeological evidence and Inuit voices. Where I’m from, Labrador, there’s a tradition of literacy within the Inuit population that goes back more than 100 years. One of the sources that I use talking about the early encounters with Europeans is a journal that was written by Lydia Campbell, a great-great-great grandmother of mine. She is recognized as the earliest known published Inuk writer in Canada. Her journal was published in newspapers in the 1890s. So, wherever I can, I use first person accounts like that, where Inuit speak in their own voices.

First-person accounts are especially important because they offer a perspective that is often less known to students. Sources in the Western tradition provide somewhat of an outsider view of Indigenous peoples. While some of these sources are informative, with modern eyes, they may look questionable and biased. I still include some Western sources among the course content, though, because they put students in the position of having to question them and analyze them for inherent biases.

C: I know you’ve been rethinking assumptions about how Western education works and trying to link students’ learning experiences with Inuit values. How do you “Inuit-ize” the course assignments?

R: To answer your question, I have to give you some background. We work at an institution that’s been created based on Western values and a Western intellectual organization of ideas and facts. And we’re all trained in the Western tradition. But I’m trying, in terms of course design, to integrate concepts related to Inuit life. Inuit society is a very flat, egalitarian society. In any society, there are people who are better than other people at doing particular kinds of things, but in Inuit society back in the day, that didn’t create hierarchy. In Inuit society, there could have been someone who was especially good at building qajaqs (boats), and someone else who was good at finding caribou, and another person who was good at creating sealskin clothing. Historically, there was no assumption that a teacher was superior to a learner. Instead, a teacher was recognized as just knowing how to do something a bit better, and therefore the teacher and learner had a relationship without any kind of hierarchy. It’s about respecting that people have different strengths and different skills, yet all contribute to society. I’d like to add that I’m deliberately trying to make the examples non-gendered. For instance, drumming was very much seen as a male role, but more and more, women in contemporary Inuit society do drumming, and that’s perfectly appropriate.

With that background in mind, I’ll give you an example of a strategy I’m going to try next time I teach the course to assess students’ participation. I’m going to ask students to reflect on their strengths, in relation to an academic exercise, on what they do well. Then, with those strengths in mind, I’m going to ask them how they would like their participation to be assessed. I know that some students are outspoken in class, but I don’t want to just privilege those students. I’d like to encourage participation in different ways, which aligns well with Inuit practices.

C: What do you believe students most appreciate about your course? What have they told you?

R: It’s relatively rare for students studying Indigenous topics to have an Indigenous instructor, and even rarer to have an Inuk instructor. Students have said they appreciate getting an Inuit perspective on Inuit issues. They get my perspective, but it’s not just about me. It’s my parents, my grandparents, and my family history. It’s about a place where we’ve lived for hundreds of years. Students appreciate the inherited knowledge.

C: What part of teaching the course do you find most meaningful?

R: It’s fulfilling to see the progression of students’ knowledge and to see them becoming progressively more reflective about what it means to experience things related to healthcare that Inuit experience in their daily lives. For example, we talk about medical evacuations, which began during the first waves of tuberculosis in the 1930s and 1940s. People were evacuated over long, long, long distances. I get students to think: “How would I feel if this were happening to me? to my family?” Medical evacuations continue today, which leads to questions, such as: “Is this really the way in which healthcare in Nunangat, the Inuit homeland, can best serve people, to be transporting them by plane thousands of kilometers to receive healthcare?” It’s important for students from radically different backgrounds to reflect deeply on what it means to be in a position of need like that, and through class discussions and assignments, I can see how students’ understanding deepens. I find it moving to see students affected in that way.

I’m also excited by the fact that this course is the first one at McGill to focus on issues around Inuit health and I, an Inuk, get to teach it! While Inuit have much in common with other Indigenous peoples, there’s also a lot of distinctiveness and specificity. So, I think it’s vital that we teach about issues like health in an Inuit-specific way. I’m thrilled to be teaching this ground-breaking course.