Dr. David Hunter Hubel, whom with his collaborator, Dr. Torsten Wiesel, shared the 1981 Nobel in Physiology or Medicine with Roger Sperry for discovering ways that the brain processes information, passed away from kidney failure on Sunday, Sept. 22, in Lincoln, Mass. at the age of 87. He was born in Windsor, Ontario to American parents and grew up in Montreal. His wife, Ruth, died in February. In addition to his son Carl, Dr. Hubel’s survivors include two other sons, Eric and Paul, and four grandchildren.

Dr. Hubel went to McGill University, where he studied math and physics. Thinking he might like to do medical research, he went on to medical school at McGill and soon found himself straining to remember every muscle in the body. But he got to spend summers at Montreal Neurological Institute, where he became fascinated with the nervous system.

After receiving his medical degree in 1951, he studied neurology at McGill for three years before heading to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore for a neurology fellowship. The Korean War interrupted his plans.

He was drafted into the United States Army and assigned to the neuropsychiatry division at Walter Reed Army Institute of Medical Research, where his efforts soon turned to the visual system. He developed an implantable tungsten electrode and a method for using it to measure the firing of brain cells in cats as they watched a moving spot on a screen. He found that cells were very selective; they fired when the spot moved in one direction but not another. Some cells did not fire at all.

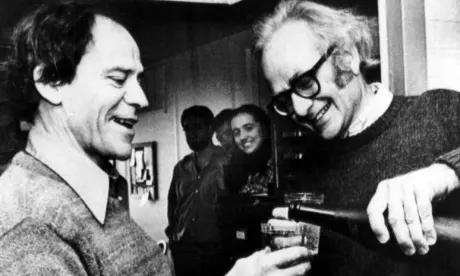

Dr. Hubel’s Army service ended in 1958, but he could not immediately resume his Johns Hopkins fellowship because the laboratory that had recruited him was being remodeled. Another Johns Hopkins neurologist, Dr. Stephen Kuffler, impressed with Dr. Hubel’s work at Walter Reed, invited him to spend a year in his lab. Dr. Kuffler paired Dr. Hubel with another young scientist interested in vision, Dr. Wiesel.

In 1959, the scientists were recruited with their mentor to Harvard Medical School, where Dr. Hubel spent the rest of his career. He maintained his lab well past his official retirement, and until January taught a freshman seminar, in which students learned to use soldering irons to build biomedical instruments, and received training in surgical techniques.

Dr. Hubel’s and Dr. Wiesel’s work further showed that sensory deprivation early in life can permanently alter the brain’s ability to process images. Their findings led to a better understanding of how to treat certain visual birth defects.

Before Dr. Hubel and Dr. Wiesel started their research in the 1950s, scientists had long believed that the brain functioned like a movie screen — projecting images exactly as they were received from the eye. Dr. Hubel and Dr. Wiesel showed that the brain behaves more like a microprocessor, deconstructing and then reassembling details of an image to create a visual scene.

Dr. Hubel and Dr. Wiesel also found that vision does not develop normally if the brain fails to make connections with the eye during a critical window early in life.

Doctors now operate on infants born with cataracts early in life to prevent vision loss; before Dr. Hubel’s and Dr. Wiesel’s research, doctors removed cataracts from infants between ages 6 months and 24 months, with poor results. The research also led to earlier treatment for strabismus, a condition in which the eyes are not properly aligned.

Scientists have since found evidence of similar “critical periods” in hearing and language acquisition.