By Gillian Woodford

Finding creative solutions to difficult problems has been a hallmark of Drs. Sylvia and Richard Cruess’ careers. When the retirement celebration and symposium that was being planned to honour their remarkable contributions to McGill had to be postponed due to the pandemic, the couple didn’t skip a beat. “We had a cocktail party in the hall,” recounts Dr. Richard Cruess. “Our friend, Pat Hamilton – she’s the widow of our old friend Richard Hamilton, Chair of Pediatrics – lives in the same building as us. In order to stick by the rules, we sat in the hallway and she sat in her doorway and –“ “– and we celebrated!” finishes Dr. Sylvia Cruess. (Having been married for almost 70 years, the Cruesses sometimes finish each other’s sentences.)

The Institute of Health Sciences Education (IHSE), which the Cruesses participated in establishing and which celebrated its one-year anniversary this week, held a ‘roast and toast’ on June 4 via Zoom in their honour as well, complete with speeches, a puppet show and (bring your own) champagne.

“The Cruesses’ passion and commitment to medical education is really beyond description,” says IHSE Director Dr. Yvonne Steinert, Professor of Family Medicine and Health Sciences Education and the Richard and Sylvia Cruess Chair in Medical Education. “They have had an impact not only at McGill, but nationally and internationally in helping people be aware of the importance of teaching professionalism and supporting professional identity formation among our learners. They have also been significant role models to all of us!”

Dr. David Eidelman, Vice-Principal (Health Affairs) and Dean of Medicine, has worked with both Cruesses over the years and heartily agrees. “I have benefited from their work as a trainee, as a junior faculty member and as a leader,” he says. “Now, as Dean, I have the perspective to understand the profound legacy they are leaving to the Faculty of Medicine, the MUHC and our community. It is truly humbling to follow in their footsteps.”

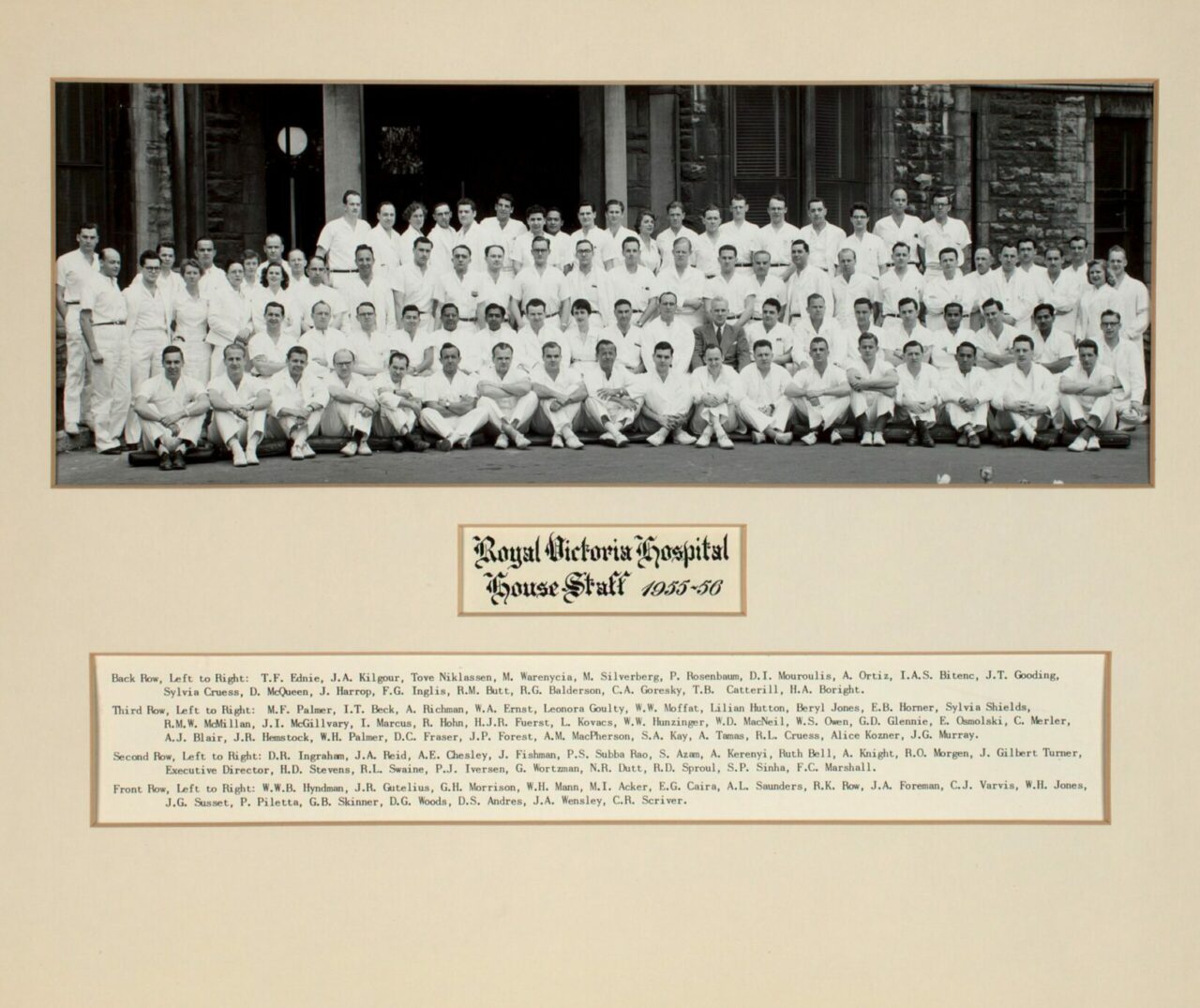

One of the Cruesses’ earliest creative solutions was the decision to come to Montreal in 1955 as rotating interns at the Royal Victoria Hospital. They had been married in their second year of medical school at Columbia University, where a computerized matching system for assigning interns to hospitals had just been brought in. “We would have had no guarantee we’d even be in the same city,” recalls Richard, a Professor of Surgery and former Dean of Medicine, who was born in London, Ontario, but raised in New Jersey surrounded by his parents’ group of Canadian expat friends. “So we came to the Royal Vic to escape the match so we could stay together.” Adds Sylvia, Professor of Medicine and former Medical Director of the Royal Victoria Hospital, who is originally from Cleveland: “We hadn’t counted on falling in love with the place!”

After their two-year stint at the Royal Vic was finished, the couple returned to New York to complete their residencies, Richard in orthopaedics and Sylvia in endocrinology. Before he could start practising, Richard had to serve two years in the US Navy medical corps as part of the Doctor Draft that existed during the Korean War and extended throughout most of the Cold War. They spent a couple more years as research fellows in New York and by 1963, they were back at the Royal Vic.

Photo courtesy McGill University Archives Photo Collection, PL006584. Photographer not listed.

Endocrinology innovator

At the time, there were more and more women graduating from medical school – “I didn’t feel as if I was breaking ground,” says Sylvia – but leadership roles for women were still rare. Columbia had been an exception. Though it had an unofficial quota of exactly 12 female students admitted each year out of 120 students, it also boasted half a dozen powerful women in leadership roles. One was Dr. Virginia Apgar, Columbia’s first female full Professor of Medicine, who introduced her famous Apgar score in 1953 while the Cruesses were students. Sylvia took inspiration from Dr. Apgar and other female leaders and made a place for herself. At the Royal Vic she says she mostly didn’t feel that gender was a huge issue in her career. “I did have one or two comments about why I wasn’t home cooking, but on the whole it was very accepting,” she recalls.

In 1967, just four years after her arrival, she was named Director of the Metabolic Day Centre. She ran the centre for 10 years, taking it from a small clinic to a pioneering day centre staffed with a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, dieticians, social workers and educators. It was the first such centre for diabetes and other endocrine diseases in Canada and inspired others across the country. “I really became convinced that a multidisciplinary team is the best way to provide care. We all worked together and it worked beautifully,” says Sylvia, who adds that the members of the team still keep in touch to this day. “It was very innovative,” says Richard. Building up the centre and being able to help patients in a much better way offered her the most satisfaction of any phase of her career, says Sylvia. “It’s the most fun I had.”

In 1977 she was appointed Medical Director of the Royal Victoria Hospital. She was the first female medical director of a hospital in Quebec and possibly in Canada. She held the role until 1995, steering the hospital through a period of extraordinary change, but always keeping one day of clinical practice. “I maintained my clinical role because when you make unpopular decisions, it’s good for the people who don’t like them to know you have to live with them too,” she says. “It made me feel better and I think it made people understand better too.”

Dr. Richard Cruess meanwhile established himself as a leading orthopaedic surgeon at the Royal Vic, performing the first total hip replacement in Montreal in 1967, all the while running a basic science lab. He notes that orthopaedic research wasn’t very strong in North America in those days, so he and his team put a lot of effort into putting McGill’s unit on the map. “We created an academic unit that was recognized around the world. We were a powerhouse in terms of research productivity and recognition,” he recalls.

Richard became Orthopaedic Surgeon-in-Charge at the Royal Vic in 1968, Surgeon-in-Chief at the Shriners Hospital in 1970, and Chair of the Division of Orthopaedic Surgery at McGill in 1976. In 1981 he became Dean of Medicine at McGill, in the midst of a turbulent political climate in Quebec.

The Parti-Québecois were re-elected in 1981 after losing the sovereignty referendum the year before. “They and the subsequent Liberal government instituted huge changes about how medicine was handled administratively from Quebec City, in particular how the education programs were run,” says Richard. “It was a very difficult time. We were faced with constant budget cuts.”

These had an enormous impact on both Cruesses, on the hospital and university fronts. “There were profound changes happening in the hospitals. Life in the medical school changed much less than in the hospitals,” notes Richard. Says Sylvia, “We had to try to manage the budgets without impacting patient care.”

One tough moment came when the government slashed the number of residency spots. “When I took over we had 1,100 residents in our programs and then four years later we were at 500,” says Richard. At the Royal Vic, Sylvia was faced with a reduced workforce almost overnight. “The only people available to replace the residents were faculty members,” she recalls. “They had to do night call, some started living in like residents.” No one was happy with the situation. The problem was partly solved by bringing in residents from the Middle East, who still play an important role at McGill to this day. “It was an opportunity to solve a problem we hadn’t predicted having,” says Richard.

It was around this time that pressure to merge hospital clinical services really started in earnest. “It wasn’t economically sustainable to maintain the General and the Vic as general hospitals about a kilometre apart, and that became clear even to the die-hards,” says Richard. (“Not to all of them!” counters Sylvia.) Eventually Sylvia and the Royal Vic leadership had to make the difficult decision to close the orthopaedic unit that Richard previously ran, moving the service to the Montreal General Hospital, while the General’s obstetrics division moved to the Royal Vic. As Dean, Richard participated in these decisions. “Were there some ruffled feathers? Absolutely. Did it work? Absolutely,” he says.

“William Osler, who is our patron saint, said you should switch career paths every decade,” observes Dr. Abraham Fuks, who followed Richard as Dean. “The Cruesses didn’t quite change every decade, but they’ve had the strength, capability and creativity to say ‘We’ve done this, we’ve done that – what’s next?’ And what’s lovely is that, in all the phases of their careers, they’ve been able to enjoy their work, all the while supporting their colleagues and those whom they nurtured.”

The Cruesses’ third career was something of a happy accident.

When Richard readily agreed to do a third term as Dean, he had one condition: that he get to take a sabbatical at the end. “Neither of us had ever had a sabbatical year – clinicians rarely do,” says Richard. Sylvia also planned to retire the same year, 1995. “We were both 65 and still intellectually and physically very active,” notes Richard. They headed off to Princeton and then Oxford, each with a project in mind. After experiencing “the intrusion of the Ministry into what had been an autonomous profession,” Richard set out to explore academic freedom in medical schools. Meanwhile, Sylvia drew on her own experience from the Royal Vic and decided to look into the idea of professionalism in medicine. “In my life, I’ve seen very good people who behave in a very unprofessional way,” she says. “Physicians who came on call drunk, physicians who abandoned their patients when there was a problem, that sort of thing.” Richard’s research yielded about 1,000 articles, mostly dry stuff about tenure. Sylvia’s yielded nothing significant in the medical literature, but she was surprised to discover that sociologists had been studying the medical profession for 100 years. “But medicine didn’t know anything about it.”

Richard persevered for a couple of months, but was increasingly drawn to Sylvia’s project: “We both got enchanted,” he says. They joined forces and before they knew it, they had embarked on a third career. “We didn’t establish what came to be called the professionalism movement. But just as we were starting to study it, the medical profession was coming under scrutiny for using its privilege to increase its control of the medical marketplace. It was total serendipity,” says Richard.

Interestingly, for a pair that seems inseparable, this was the first time they had ever worked directly on a project together. “When we started writing papers, she took out parts I’d written that I thought were wonderful, and I did the same to her,” says Richard, laughing. “So it took us a little while to figure out the interpersonal issues…” “…but we managed,” finishes Sylvia, adding, “But he still takes out all my good things!”

There was no grand plan at the outset. “We got lucky,” says Richard. Dr. Fuks had taken over as Dean and gave them a lot of space, through the Centre for Medical Education (now IHSE), to explore how to define and teach professionalism to both medical students and doctors. Working with colleagues like Dr. Don Boudreau, Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine and the IHSE, and Dr. Steinert, they developed a curriculum and a pretty solid definition.

Still, everywhere they went they were constantly challenged by doctors with the question, “Shouldn’t everybody know this?” Says Richard, “We didn’t really have an answer.” The Cruesses struggled with it until about five years ago when they hit upon the concept of identity formation from the field of developmental psychology that was being applied to medical education. They define it as the acquisition of an identity to become part of a community. When someone becomes a physician, they are taking on an identity and a role in a community and committing to a social contract. The program they helped to develop most recently, which shifted the focus from teaching professionalism to supporting learners as they develop their professional identity and become who they wish to become, has transformed the way medicine is taught at McGill and around the world. “Some medical students chose McGill because of it,” says Sylvia.

Photo credit: Owen Egan

A remarkable legacy

The Cruesses feel confident that their goals and aspirations will continue, under the able guidance of those who will continue to teach and study at the IHSE, even if the approaches evolve – which is as it should be, they say.

Two younger scholars who have taken up the mantle are Drs. Robert Sternszus and Joanne Alfieri.

“In many ways I feel that I owe my entire career to Dick and Sylvia,” says Dr. Sternszus, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Health Sciences Education. “They have been my role models and mentors. As teachers when I was a medical student they exposed me to the concepts of professionalism and sparked my interest in the field. They subsequently nurtured that interest by supporting and guiding me through my first research project, and over the last 10 years they have consistently thought of and included me in conference presentations, books that they were editing or articles that they had been asked to write.”

Dr. Alfieri, radiation oncologist at the MUHC, Assistant Professor and Director of Education, Gerald Bronfman Department of Oncology, and Richard and Sylvia Cruess Faculty Scholar in Medical Education, also met the Cruesses as a medical student. “They were icons, but they were always ready to contribute their expertise and advice to any project, no matter how small,” she says. “Eventually, it was the spark that led me to embark on a Master’s in Medical Education with the University of Dundee after the completion of my clinical fellowship.” Now, in the spirit of her mentors, Dr. Alfieri is carrying out research that will help guide McGill through the upcoming curriculum shift from a time-based model of residency training to a competency-based one.

“We never achieve everything we want to do, but we feel closer than ever now,” says Richard. “The stuff we’ve published in the last five years with our colleagues has really been intellectually and emotionally the most satisfying part of our careers because we have arrived, at McGill, at an understanding of what our real role as an educational institution is.”

That their colleagues don’t believe they’re really leaving shows how integral they are. “I’m not convinced their work is finished yet,” says Dr. Steinert, who has known the Cruesses for nearly three decades. “I know they’re officially retiring, but my guess is they will continue to be involved, and we would be happy and honoured if they were.”

She might just get her wish. “We hope we’ll have a desk and a computer in the Institute,” ventures Richard, who does admit he’s looking forward to not feeling like he has to go into the office everyday, adding that working from home during the pandemic has given them a chance to practise. “Though I won’t pretend we’ve been very productive these last few weeks!”

As the Cruesses’ fourth career – as retirees – begins, how do they plan to fill their time (once the pandemic is over, that is)? They hope to do a little bit of travelling and also enjoy their major hobby, attending classical music performances. When we spoke, they were preparing to hunker down for an extended, well-deserved holiday at their summer place in Ontario. “We won’t be bored!” they promise.

June 11, 2020