This is the August installment of our series highlighting the McGill Faculty of Medicine’s contribution to the city of Montreal in honour of its 375th birthday.

By Gillian Woodford

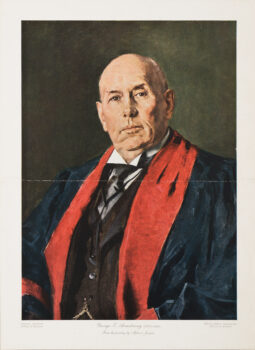

A noted innovator in an era of rapid change, former McGill University Dean of Medicine Dr. George Eli Armstrong is credited with being the first in Montreal to champion two revolutionary medical practices at the turn of the last century: radium and endotracheal anaesthesia. “Armstrong was really at the forefront in using new technologies,” notes Dr. Thomas Schlich, James McGill Professor in History of Medicine at the Department of Social Studies of Medicine at McGill’s Faculty of Medicine.

Dr. Armstrong was born in Leeds, Quebec in 1855 and received his medical degree from McGill followed by postgraduate training in Europe. He was a surgeon at the Montreal General Hospital (MGH) until 1911 when he was appointed Chief of Surgery at the Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH), a position he held along with his academic position at McGill until his retirement in 1923. He served as a surgeon during World War I and was Dean of Medicine at McGill for one year before he retired. He died in 1933.

Radium craze

Radium was discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898, and isolated by Marie Curie in 1902 as radium chloride. The radioactive element’s

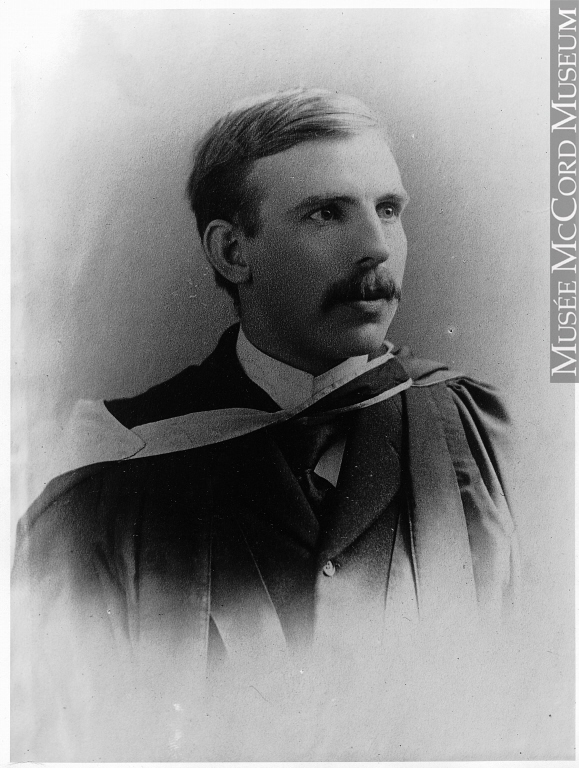

therapeutic potential was immediately recognized. “Medical researchers noticed that radium could destroy or alter tissues,” says Dr. Schlich, “and there was a rush of interest before the First World War as many doctors tried to discover a use of radiation for medicine.” Canada was a little late to the game despite having a hugely important claim on radium research: famed physicist Ernest Rutherford, whose work on radium and radioactivity was closely intertwined with the Curies’, discovered the process of spontaneous disintegration of atoms, as well as identified alpha, beta and gamma rays, while working at McGill in the early 1900s. “Then in 1909 a group of Canadian doctors who tried to catch up went to the Institut du Radium in Paris and one of them was George Armstrong,” says Dr. Schlich.

Upon his return, Dr. Armstrong published a report of his visit in the Montreal Medical Journal. He was cautiously optimistic in his appraisal of radium, echoing the reticence of the Institut’s own researchers. “A definite opinion cannot be given until a larger experience is obtained and a longer time has elapsed,” he writes, adding, “There are reasons for thinking that radium has a selective action on cancer cells.”[1] Armstrong goes on to describe some cases he was presented, including leukoplaki, epithelioma and vascular naevi, or birthmarks. On the last he was quite enthusiastic: “The apparatus is generally applied and held in place by a strip of adhesive plaster. As these patients are often infants, the absence of pain or discomfort obviating the necessity of any local or general anaesthesia is a valuable feature.”[2] Affixing radioactive substances to infants might strike us as reckless, but as Dr. Schlich notes, “Doctors and scientists had no idea of the damage and used it for minor problems.” Radium was also used as an experimental treatment for eczema, impetigo, pruritus and haemorrhoids, with varying results.

It is difficult to say if Dr. Armstrong ever actually employed radium on any of his patients, though there are anecdotal claims he brought the practice to Montreal. Dr. Armstrong’s interest in radium appears to be more to disseminate a new scientific discovery to his colleagues rather than to implement a still-uncertain therapy. In 1922, Montreal established its own Institut du Radium, which became the centre for radiation therapy in Canada. In 1929-30, two decades after Dr. Armstrong’s trip to Paris, the MGH and RVH set up their own Radium Departments.[3]

Intratracheal insufflation

Dr. Armstrong was very much at the forefront in his own field, surgery, as an early adopter of “intratracheal insufflation,” better known today as endotracheal anaesthesia or intubation. The procedure, in which a flexible tube is placed in the trachea to keep the airway open as well as to administer anaesthesia during surgery, was first used in 1910 by New York surgeon Charles Elsberg. Dr. Armstrong seems to have heard of the technique at the 1911 meeting of the American Surgical Association. “Dr. Armstrong was impressed by the technique and within a year he reported its use in fifty cases,” writes Dr. F. N. Gurd.[4] Dr. Armstrong’s colleague at the MGH, the anaesthetist Dr. William G Hepburn adds that “in 1911 [intratracheal ether insufflation] was brought into use in the Montreal General Hospital and has been constantly employed there ever since.”[5] Dr. Armstrong brought the practice with him when he moved to the RVH. Although it revolutionized anaesthesia and is now standard, intratracheal insufflation would not become commonplace for three more decades.

[1] George Eli Armstrong, “On the use of radium in Paris,” Montreal Medical Journal, Vol. 38, no. 6 (June 1909), page 379.

[2] ibid, page 378.

[3] Charles Hayter, Element of Hope: Radium and the Response to Cancer in Canada, 1900-1940, page 49.

[4] F. N. Gurd, The Gurds, the Montreal General and McGill: A family Saga. Montreal, General Store Publishing, 1996, page 99.

[5] William G. Hepburn, “Intratracheal Ether Insufflation,” Anesthesia and Analgesia, Oct. 1922, page 83.

August 31, 2017