IFIT antiviral protein recognizes foreign RNA and blocks viral infection

Researchers at McGill University and the Research Center for Molecular Medicine (CeMM) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences have discovered the molecular blueprint behind the IFIT protein. This key protein enables the human immune system to detect viruses and prevent infection by acting as foot soldiers guarding the body against infection. They recognize foreign viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) produced by the virus and act as defender molecules by potentially latching onto the genome of the virus and preventing it from making copies of itself, blocking infection. The findings are a promising step towards developing new drugs for combatting a wide range of immune system disorders.

Researchers at McGill University and the Research Center for Molecular Medicine (CeMM) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences have discovered the molecular blueprint behind the IFIT protein. This key protein enables the human immune system to detect viruses and prevent infection by acting as foot soldiers guarding the body against infection. They recognize foreign viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) produced by the virus and act as defender molecules by potentially latching onto the genome of the virus and preventing it from making copies of itself, blocking infection. The findings are a promising step towards developing new drugs for combatting a wide range of immune system disorders.

The discovery was made by teams led by Bhushan Nagar, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry at McGill’s Faculty of Medicine, and Dr. Giulio Superti-Furga at the CeMM. Building on the 2011 CeMM discovery by Dr. Andreas Pichlmair that IFIT proteins unexpectedly interact directly with the viral RNA to inhibit its replication, the group’s latest discovery reveals the molecular mechanism behind how IFIT proteins capture only the viral RNA and distinguishes it from normal molecules belonging to the host. Their research is published in the January 13 issue of the journal Nature.“Infection by pathogens such as viruses and bacteria are caught by a layer of the immune system that consists of guard-like proteins constantly on the lookout for foreign molecules derived from the pathogen,” explains Prof. Nagar. “Once the pathogen is detected, a rapid response by the host cell is elicited, which includes the production of an array of defender molecules that work together to block and remove the infection. The IFIT proteins are key members of these defender molecules.”

When a virus enters a cell, it can generate foreign molecules such as RNA with three phosphate groups (triphosphate) exposed at one end, in order to replicate itself. Triphosphorylated RNA is what distinguishes viral RNA from the RNA found in the human host. During this time, the receptors of the innate immune system are usually able to detect the foreign molecules from the virus and turn on signaling cascades in the cell that leads to the switching on of an antiviral program, both within the infected and nearby uninfected cells. Hundreds of different proteins are produced as part of this anti-viral program, which work in concert to resist the viral infection.

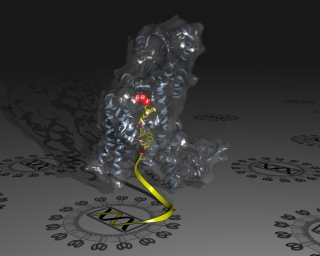

In the Nagar lab, McGill graduate student Yazan Abbas used an arsenal of biophysical techniques, most notably X-ray crystallography, to capture the IFIT protein directly in the act of recognizing the foreign RNA. The work shed light on the interaction between IFITs and RNAs. The researchers determined that IFIT proteins have evolved a specific binding pocket, chemically compatible and big enough to fit only the triphoshorylated end of the viral RNA. Human RNA is not able to tightly interact with this pocket, thereby circumventing autoimmune reactions.

“Once the IFIT protein clamps down on the viral RNA, the RNA is then presumably prevented from being used by the virus for its own replication,” says Superti-Furga, “Since many viruses, such as influenza and rabies, rely on triphosphate RNA for their lifecycle, these results have widespread implications in understanding how our cells interact with viruses and combat them.”

This work could help advance the development of new drugs for combating a wide array of immune system disorders. “Our findings will be useful for the development of novel drugs directed at IFIT proteins, particularly in cases where it is necessary to dampen the immune response, such as inflammation or cancer therapy,” says Nagar.

Related coverage

Sun News

January 15, 2013

When a virus enters a cell, it can generate foreign molecules such as RNA with three phosphate groups (triphosphate) exposed at one end, in order to replicate itself. Triphosphorylated RNA is what distinguishes viral RNA from the RNA found in the human host. During this time, the receptors of the innate immune system are usually able to detect the foreign molecules from the virus and turn on signaling cascades in the cell that leads to the switching on of an antiviral program, both within the infected and nearby uninfected cells. Hundreds of different proteins are produced as part of this anti-viral program, which work in concert to resist the viral infection.

In the Nagar lab, McGill graduate student Yazan Abbas used an arsenal of biophysical techniques, most notably X-ray crystallography, to capture the IFIT protein directly in the act of recognizing the foreign RNA. The work shed light on the interaction between IFITs and RNAs. The researchers determined that IFIT proteins have evolved a specific binding pocket, chemically compatible and big enough to fit only the triphoshorylated end of the viral RNA. Human RNA is not able to tightly interact with this pocket, thereby circumventing autoimmune reactions.

“Once the IFIT protein clamps down on the viral RNA, the RNA is then presumably prevented from being used by the virus for its own replication,” says Superti-Furga, “Since many viruses, such as influenza and rabies, rely on triphosphate RNA for their lifecycle, these results have widespread implications in understanding how our cells interact with viruses and combat them.”

This work could help advance the development of new drugs for combating a wide array of immune system disorders. “Our findings will be useful for the development of novel drugs directed at IFIT proteins, particularly in cases where it is necessary to dampen the immune response, such as inflammation or cancer therapy,” says Nagar.

Related coverage

Sun News

January 15, 2013