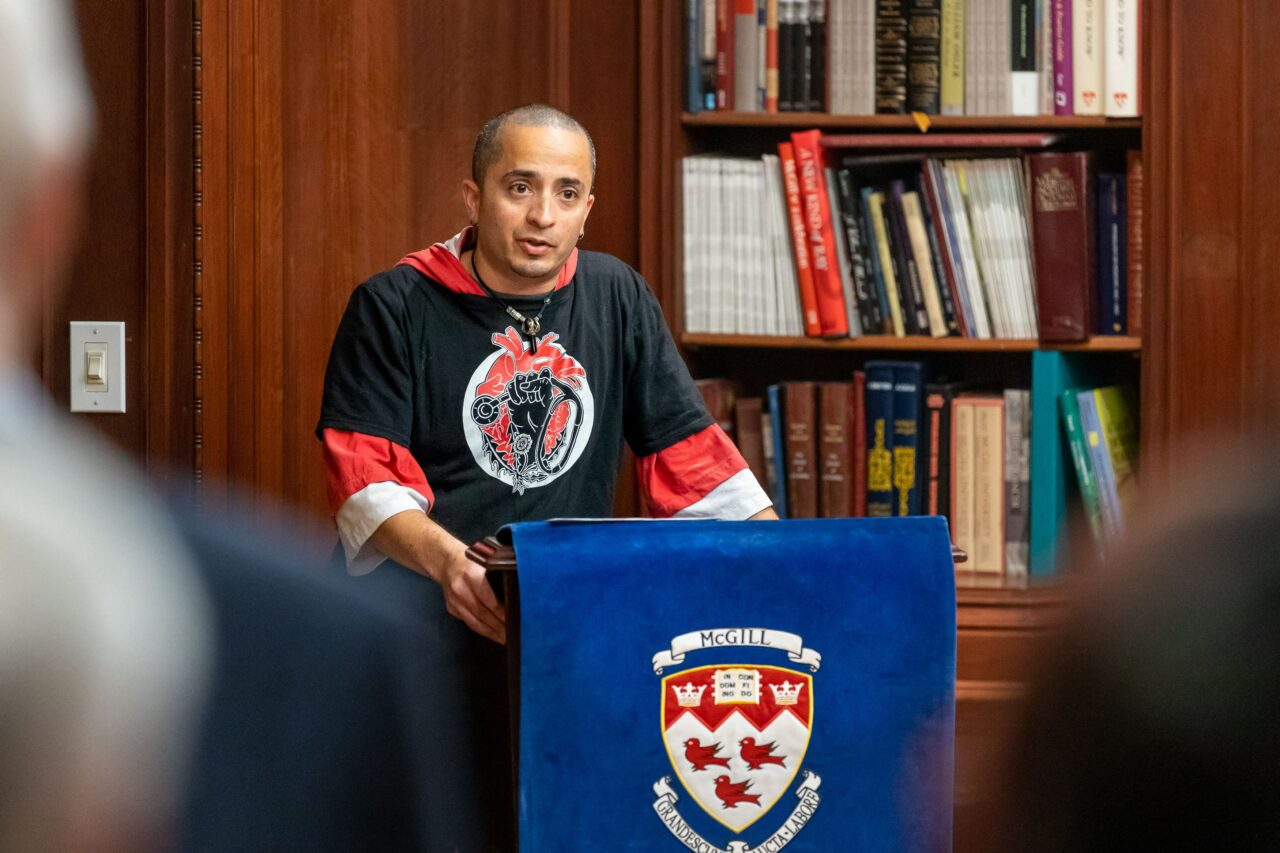

Samir Shaheen-Hussain, MDCM, is this year’s recipient of the Haile T. Debas Prize, established in 2010 to recognize Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS) members who promote the ideals of equity and anti-racism through practical action. Dr. Shaheen-Hussain, who was recently promoted to Associate Professor, was Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics when the prize was awarded; he is also an Associate Member of the School of Population and Global Health and a pediatric emergency physician at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. For more than 20 years, he has been involved in social justice movements, and is currently part of the Caring for Social Justice Collective. In 2020, he published Fighting for A Hand to Hold: Confronting Medical Colonialism against Indigenous Children in Canada (foreword by Cindy Blackstock and afterword by Katsi’tsakwas Ellen Gabriel), which has garnered widespread acclaim and won several awards. We sat down with Dr. Shaheen-Hussain to discuss how he became involved in social justice work and his thoughts on effecting real change towards healthcare equity.

When did you first become interested in the areas of social justice and healthcare delivery?

A few key experiences catalyzed my politicization process. After my first year of medical school, I was part of a volunteer summer elective at a pediatric hospital in Rabat, Morocco. Then, in third year, I did a family medicine rotation in Sioux Lookout in northern Ontario. It was jarring to witness injustices on both global and local levels, and they hit hard because children were often most harshly impacted. Around the same time, I saw and, at times, faced the racist backlash following the 9/11 attacks in the United States. Together, these experiences transformed my worldview to understand how dominant systems and structures create suffering but also how people organize collectively to resist and fight back for their health, safety, and dignity.

Did your social justice work play a part in choosing to become a pediatric emergency physician?

Not specifically, but I had wanted to work with kids as long as I can remember. I’m privileged and humbled to work as a pediatric emergency physician. Maintaining clinical excellence is a responsibility I take seriously given the role we play for children and their families during particularly vulnerable moments in their lives. My clinical work is also very grounding and serves as a strong impetus for effecting change because I witness first-hand the impacts of harmful social, economic, and political realities on children, their families and their communities, all of which also impact on the fabric of our society more broadly.

Engaging with children and youth in various spheres of my life–often being marked by their curiosity and resilience–has certainly inspired my social justice work.

Is there a specific moment that has left a lasting impact on your social justice work?

When I was young, I recall being struck by pictures of family members at protests against war and occupation, including a demonstration in Montreal in solidarity with the Kanien’kehá:ka resistance during the 1990 Siege of Kanehsatà:ke (commonly referred to as the Oka Crisis).

In 2002, I was part of a group of McGill students who formed the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Movement, and Katsi’tsakwas Ellen Gabriel was then the director of the First Peoples’ House. She played a key mentorship role for many of us, and has remained a dear friend ever since. Her unwavering and fierce commitment to struggles for Indigenous sovereignty, environmental justice, and human rights spanning more than 30 years is truly an inspiration.

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the many educators, activists, mentors, and friends who continue to teach me about decolonization and social justice by modeling what radical solidarity means on the ground.

When you accepted your award, you mentioned the COVID-19 pandemic and the deaths of George Floyd and Joyce Echaquan exposing “the fault lines of societal injustices on a global scale.” Do you think any real change has started happening since those terrible events?

Important steps have been taken in health care and academia such as the adoption of Joyce’s Principle by the FMHS and the MUHC, but we cannot rely on the same economic, political, and social systems that have produced entrenched injustices to help us put an end to them.

We live in a time fraught with uncertainty and anxiety about our collective future. We have to think creatively, courageously, and collaboratively to carve out new possibilities, making sure that no one is left behind, and work together to build a new world where it is easier to be empathetic, to prioritize cooperation, mutual aid, and solidarity, to respect human dignity, and to live in harmony with our ecosystems. Academic and healthcare institutions can have an important role to play in this, but tangible and sustained change can’t occur without urgent commitments and actions towards a fundamental re-structuring of society.

Dr. Shaheen-Hussain has directed his Prize money to five McGill groups: the Indigenous Health Professions Program, First Peoples’ House, the Welcome Haven project, the Office of Social Accountability and Community Engagement, and the Department of Pediatric Chair’s discretionary fund.

Related:

Award-winning book by McGill professor takes on systemic racism in health care

French edition of Fighting for a hand to hold wins translation prize

Parents should be able to accompany children during health-related air transport, McGill profs say

Fighting for a hand to hold: https://fightingforahandtohold.ca

Photos: Owen Egan and Joni Dufour