By Matthew Brett

Digital medicine and its consequences for teaching and learning will be the subject of the next Medical Education Rounds, scheduled for February 14 with Dr. Jörg Goldhahn of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

The field of medical education broke with tradition after World War II, looking outside of itself to “far-reaching and even radical cultural reference points” to signal the field’s modernist rise in global importance, argued Dr. Annmarie Adams, Chair of the Department of Social Studies of Medicine at McGill University, to a full house last Thursday.

“The built environment can reveal much about the unwritten priorities of medicine,” Adams told some 50 attendees of last week’s Medical Education Rounds, an ongoing series of talks co-hosted by McGill’s Centre for Medical Education and the Faculty Development Office.

The Stevenson Chair in the Philosophy and History of Science, Adams’s presentation stemmed from her contribution to a proposed book, Medical Education: A History in 20 Case Studies, edited by Delia Gavrus and Susan Lamb, about the global history of medical education.

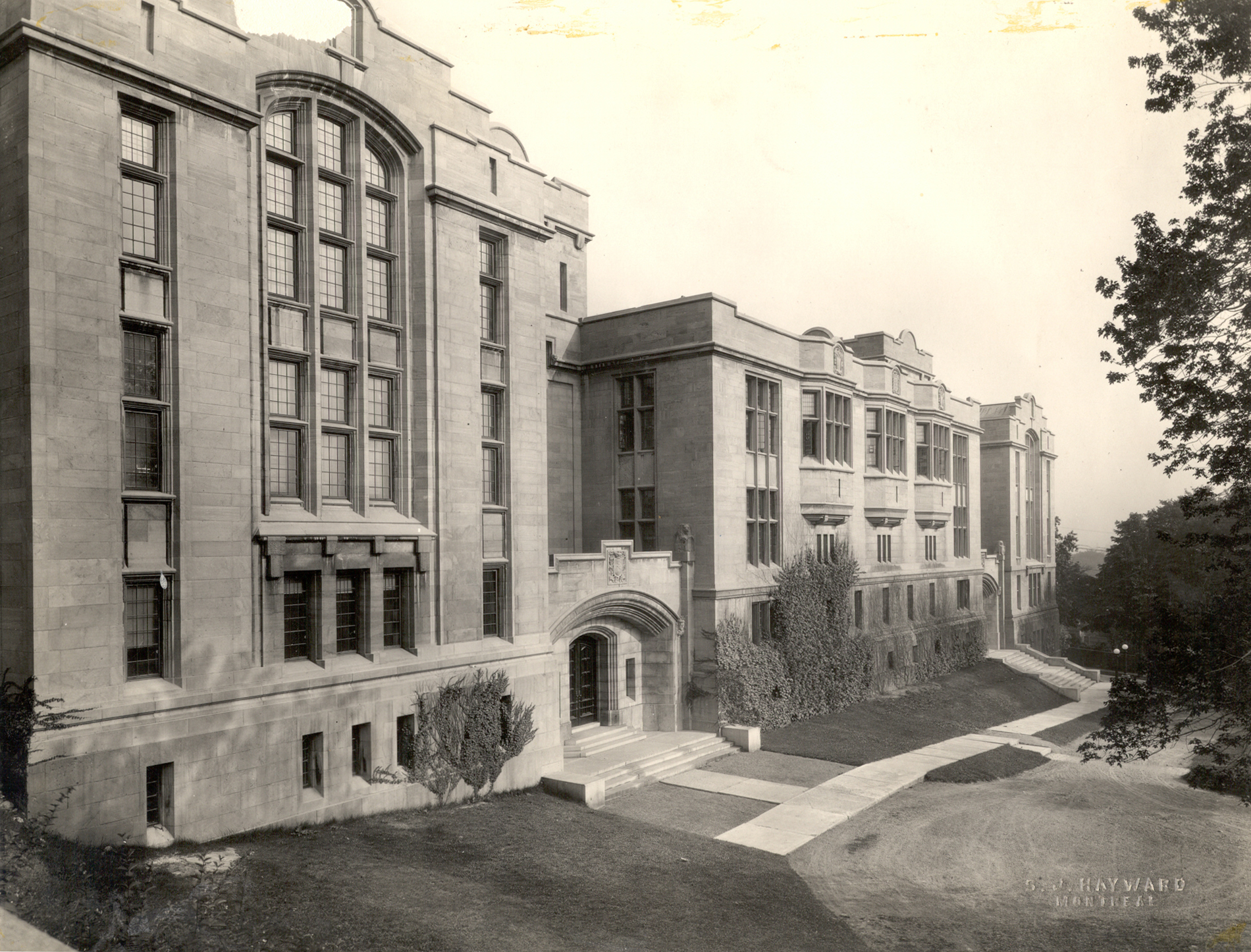

As the first medical faculty in Canada, McGill University features prominently in her work as its early medical curriculum influenced other Canadian medical schools, and two of three of the university’s purpose-built medical buildings are still used as medical-school buildings today.

Social and cultural histories of medical education tend to rely on textual evidence, but Dr. Adams proposes utilizing architecture itself as primary source material.

“What does architecture tell us about medical education?” Dr. Adams asked the audience.

Design decisions and archival drawings “reflect and shape the medical curriculum, illustrating the varying importance of educational components such as research, dissection, display, reading, lecturing and discussion,” she continued.

The audience was encouraged to engage in a practice of “looking around,” as Dr. Adams adopts a “purposefully conversational” approach akin to a guided tour in order to understand nearly a century of medical education at McGill by walking through its architecture.

Pre-war medical education architecture

Walking together through Dr. Adams’s narrative and archival slides, the audience learned of the original Old Medical, designed in 1872, and its dramatic fire of 1907.

The Strathcona Medical Building that replaced the Old Medical was strategically placed between the university and the Royal Victoria Hospital, designed for students to understand the branches of medicine as parts of a whole.

The floor plan shows the prominence of disciplines like anatomy in the medical education curriculum of 1911, as it occupied the whole east wing of the new structure.

The medical education buildings of this time looked much like other, non-medical university buildings, apart from their unique programs that required specialty spaces like laboratories, accommodations for animals, specialized backstage areas, morgues, and facilities for animal care, cleaning, and dissection.

The McIntyre Medical Building opened in 1966, marking a radical departure from McGill’s pre-war medical education practice and architecture.

At nearly 312,000 square feet, the McIntyre accommodated 10 percent of the whole university and is still the tallest building at McGill. Its geographic prominence and distinct design were intended to signal a new era in medical education.

Drawing from cultural reference points widely outside the medical field, the McIntyre has a massive car port common in postwar utopian designs, fashionable entrances, and references to a global, tech-savvy era captured in the spirit of Expo 67.

The practice of medical education also ruptured from its classical origins with an emphasis on integrated research and teaching manifested in the proximity of labs and classrooms.

“Teaching and research have become inseparable,” exclaimed Dean Ronald V. Christie at the building’s opening.

A competitive drive to modernize saw a new “systems” approach to curriculum emerge, with body systems taught in integrated blocks showcasing diagnosis and treatment, rather than from the perspective of more siloed disciplines.

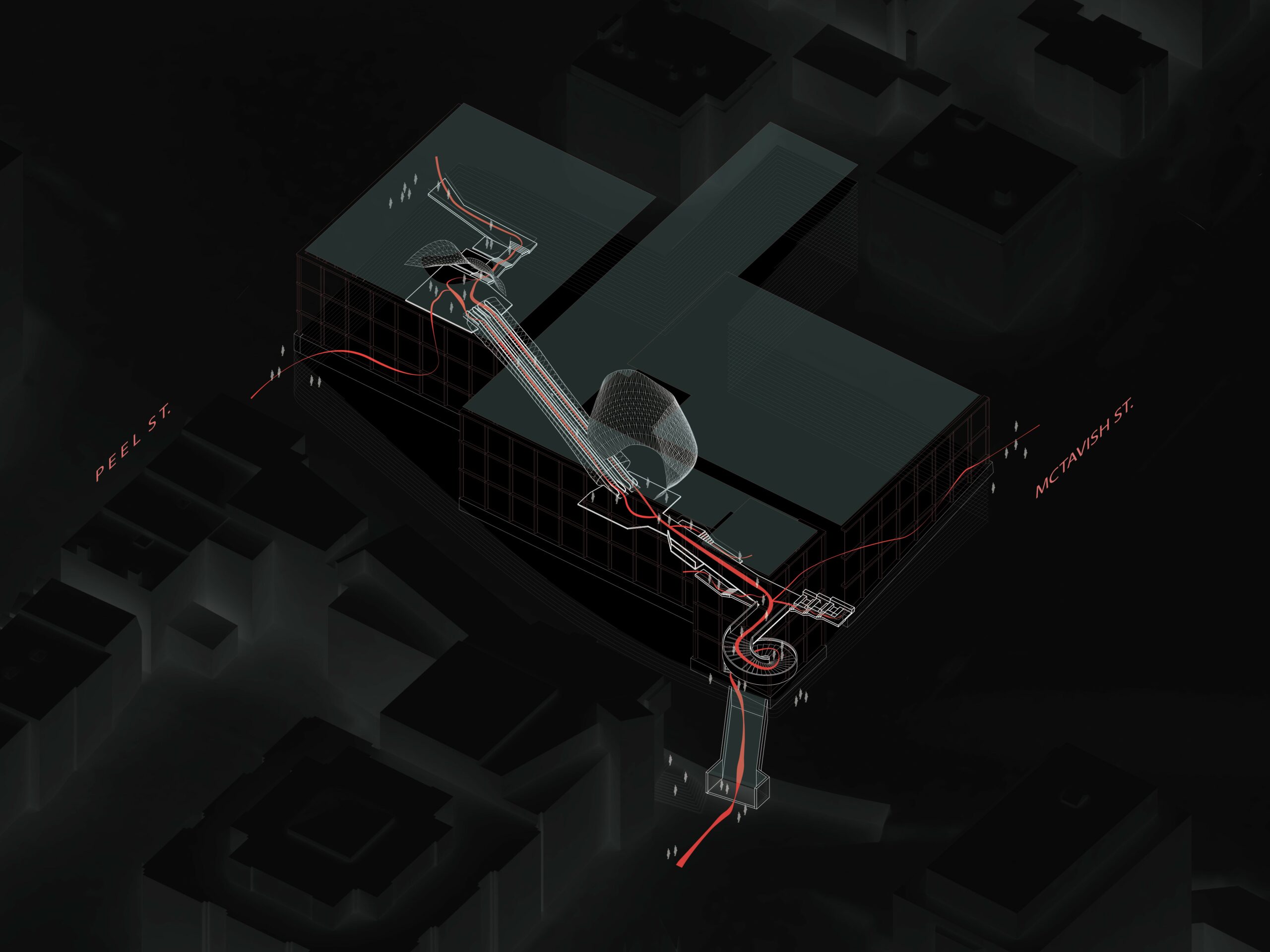

Looking forward to the future of medical education, Dr. Adams showed the audience a rendering by architecture Master’s student Philippe Saurel.

Based on a suggestion from Dr. Adams that he take on a building with some current real-world relevance, Philippe is presently designing a medical school building for the Powell site as part of his Master thesis, entitled “You Can’t Teach This: A Learner-Centered Medical Teaching Facility,” and was present at the event.

The image—shown publically for the first time at this event—is strikingly futuristic with an emphasis on flow and urban circulation in a city of movement and global vitality.

What does the future have in store for medical education? Dr. Adams reminds us we stand to learn a great deal from looking around.

December 6, 2018