Source: Ingram School of Nursing

Source: Ingram School of Nursing

The School’s second director and author of influential textbook on nursing

It is surprising to learn that one of the most important people in the history of nursing only began her career at the age of 30. Bertha Harmer was born in Port Hope, Ontario, in 1880. When Harmer was an adolescent, her family moved to Toronto where Harmer attended Lord Dufferin Public School, then Jarvis Street Collegiate Institute. Upon graduation, she went to work for the William Davies Company Limited. Harmer spent almost 10 years at the company until a fellow employee encouraged her to pursue a career in nursing. In 1910, when hospital-based programs were the only nursing education available in Canada, she enrolled in the Toronto General Hospital Training School for Nurses.

Harmer excelled in her studies, and graduated first in her class in 1913. She stayed on at Toronto General to teach and also held nursing and administrative roles. Two years later, she moved to New York City to study at Teachers’ College, Columbia University. She also nursed and taught at St. Luke’s Hospital, and continued to teach there after her graduation in 1918. It was during this time she wrote her influential and groundbreaking textbook The Principles and Practice of Nursing, a work that would become the standard for nursing education for decades. The first edition was published in 1922, and in her lifetime, two more editions would be published.

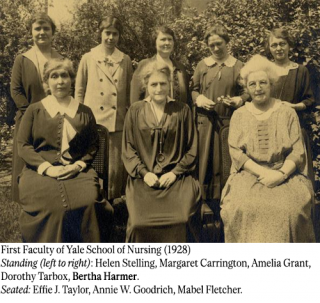

In 1923, Harmer left New York City to teach at the Yale University School of Nursing where she helped establish the first university degree in nursing. While there, she authored the first textbook on nursing education, Methods and Principles of Teaching the Principles and Practice of Nursing (New York, 1926), which, together with her first book, established her reputation as a leader in nursing. The following year, Flora Madeleine Shaw, the first director of the School of Graduate Nurses at McGill University, died suddenly. McGill invited Harmer to take on the director’s role and in 1928, she moved to Montreal.

Ensuring the School’s survival

Ensuring the School’s survivalUpon its founding in 1920, the School of Graduate Nurses at McGill had the goal of creating a degree program. Harmer’s leadership was intended to accelerate that aim and she worked towards advancing the program through curriculum revisions, appointing new faculty members and developing new projects. The School was counting on private funding to move the program forward but these pledges virtually disappeared with the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed. By 1932, McGill’s board of governors decided that the school would have to be closed unless five years’ funding could be secured.

Harmer, by this time, was in declining health but with support from alumni she began a significant fundraising campaign led by McGill’s principal, Sir Arthur William Currie. Their efforts succeeded in keeping the School open. There were still difficulties throughout the remainder of the 1930s, but the School survived and eventually offered a bachelor of nursing degree in 1944. Harmer did not live to see the fruits of her labour: due to failing health, she resigned from the School in May 1934, and died in December the same year.

Ahead of her time

Harmer’s legacy is the foundation for the strengths-based nursing model of today. The nursing concept of ‘human needs’ was a core idea in her work and thinking, and she encouraged nurses to see “the patient as a whole person, a human being, a member of a family and of the community.”

Harmer was also a pioneer in integrating practice with education, as she wrote in Methods and Principles of Teaching the Principles and Practice of Nursing. “Students can’t help themselves and will make little progress in learning unless the environment and the situations which we create around them provide the opportunity, the stimulus, encouragement, and practice in meeting and solving problems by their own thinking, their own initiative, and their own responsibility as far as the patient’s and their own welfare permits.” Her thinking is as relevant today as it was in her time.

March 12 2020