By Marlene Busko

To learn a new word, a child with autism might rely on strategies such as mapping it to a visually salient object or remembering the word’s sound, rather than using social cues such as a speaker’s direction of gaze. “Are these the same strategies that we see used in typically developing children, or are they alternate strategies to get to the same point?” asks Aparna Nadig, PhD, Assistant Professor at McGill’s School of Communication Sciences and Disorders. Nadig and her team are nearing completion of a year-long, six-part study that will shed light on vocabulary growth over time in children with autism.

At her office on the top floor of the Beatty Hall heritage building, Nadig explains that the “POP” lab name is an acronym for “psychology of pragmatics,” where “pragmatics” refers to social aspects of communication.

A major area of focus in her work is language delay, a common trait among those with autism. However, this type of impairment spans a broad range, and some children with autism are more adept at learning new words. Children with better early language skills are more likely to grow up to be high functioning, independent adults.

“The main point of the current study is to figure out what mechanisms underlie this range of differences and try to identify strategies being used by the kids who are picking up and generalizing a lot of vocabulary,” explains Nadig. A better understanding of these processes could help guide future therapies for language development in children with autism.

According to Nadig, this study could have important clinical implications by providing insights into possible ways to help children with autism spectrum disorders communicate more effectively. For example, it might confirm that subtle things parents can do when interacting with their child — such as following their child’s focus of attention and using multiple cues when labeling an object — may help facilitate language development, explains Nadig.

The study will also provide groundbreaking data from Francophone children with autism. “To date, all careful research on processes of language development in autism has been done in English, so we’re going to be adding substantially to the literature by doing the parallel study in Québecois French,” explains Nadig.

The target enrollment for the study is 80 children. This includes 20 Anglophone children with autism spectrum disorder who are two to six years old at enrollment and who are matched for language skills with 20 typically-developing Anglophone children who are 15 months to two years old at enrollment.

In parallel, the study is enrolling two similar groups of Francophone children. Recruitment of Anglophone children has been completed and many of the children will be finishing the study this spring, with the Francophone study well underway.

The typically-developing children were drawn from the McGill Infant Recruitment Group (MIRG) research database. The children with autism spectrum disorders were recruited primarily from the Autism Spectrum Disorders Program at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

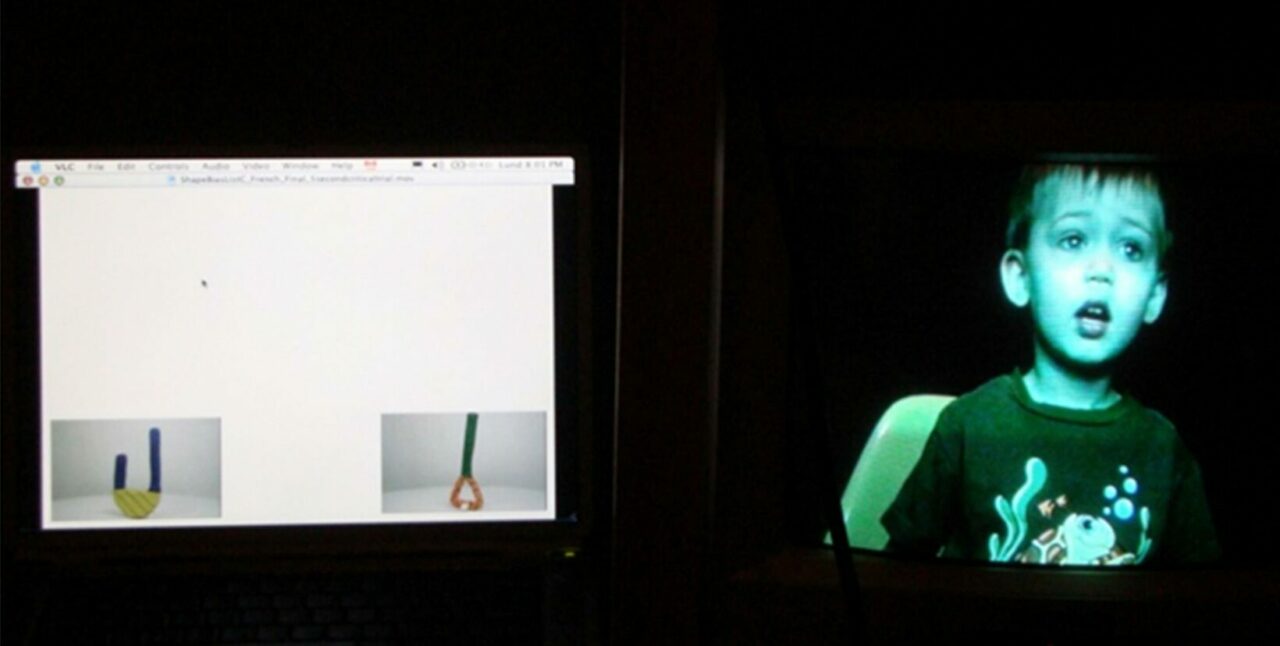

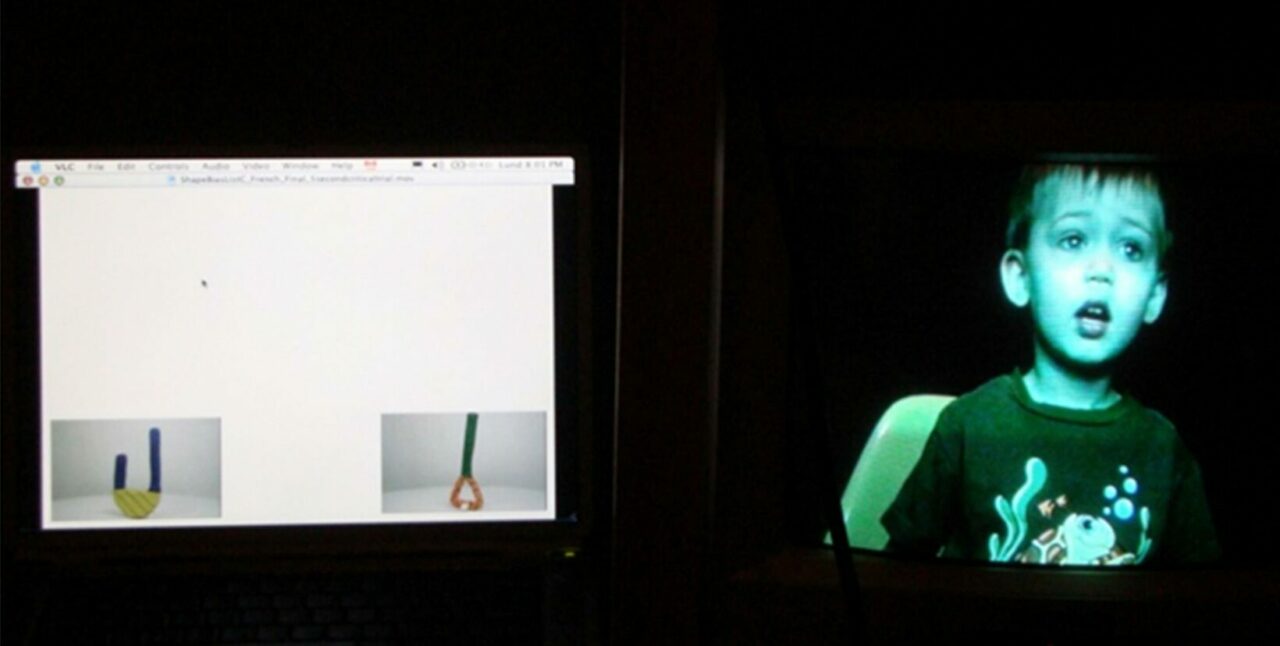

Parent and child study participants make three visits to the McGill Language Aquisition lab, located in the Stewart Biological Sciences building: an initial, one-and-a-half-hour visit, a 30-minute visit six months later, and a third visit a year after the initial visit. At the beginning and end of the study the children take part in a standardized test that measures their language skills, and the parents fill out a questionnaire about their child’s vocabulary, providing a measure of language growth over the year. Children also take part in a range of experimental tasks, and impromptu play is part of the sessions.

Preliminary findings from three parts of the six-part study have been accepted as posters for the IMFAR (International Meeting for Autism Research) meeting in San Diego, in May. One poster examines child-directed speech or “motherese” and its relationship to greater vocabulary gains. A second poster, based on parent-child interactions during free play, suggests that children with autism spectrum disorders use less “pretend” play and their parents are more likely to redirect the child’s attention. A third poster suggests that children with autism who have higher language abilities are able to learn words by following social cues.

The fourth part of the study looks at how children generalize new words to other objects in the same category. The fifth part investigates what cues parents naturally use to label objects for their children in a play setting. The sixth part examines how statistical properties of parental speech are related to the child’s vocabulary. After the final data from all parts of this study has been obtained and analyzed, the group will submit manuscripts to medical journals.

“A study of this nature involves the ongoing dedication of members of my whole team, who have been essential to its conduct,” Nadig emphasizes. In addition to leading her research team, she teaches courses for graduate students in speech pathology, including one on autism spectrum disorders.

This combination of research and teaching is what drew Nadig to McGill, and it builds on her earlier training. She studied developmental pragmatics in the normal population and obtained a PhD in cognitive science from Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island. From that work, she became interested in autism, which led to doing an intensive post-doc at the UC Davis MIND (University of California, Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders) Institute, where she trained with psychologists who are experts in autism. Part of her work included a project to see if autism could be detected at 12 months based on a child’s lack of response when called by his or her name.

“McGill’s Communication Sciences and Disorders program is the most research-focused of anywhere that I know,” says Nadig, adding that “given my two aspects of training, this is a perfect fit because I’m able to keep doing basic science research, and teach future practitioners.”

To learn a new word, a child with autism might rely on strategies such as mapping it to a visually salient object or remembering the word’s sound, rather than using social cues such as a speaker’s direction of gaze. “Are these the same strategies that we see used in typically developing children, or are they alternate strategies to get to the same point?” asks Aparna Nadig, PhD, Assistant Professor at McGill’s School of Communication Sciences and Disorders. Nadig and her team are nearing completion of a year-long, six-part study that will shed light on vocabulary growth over time in children with autism.

At her office on the top floor of the Beatty Hall heritage building, Nadig explains that the “POP” lab name is an acronym for “psychology of pragmatics,” where “pragmatics” refers to social aspects of communication.

A major area of focus in her work is language delay, a common trait among those with autism. However, this type of impairment spans a broad range, and some children with autism are more adept at learning new words. Children with better early language skills are more likely to grow up to be high functioning, independent adults.

“The main point of the current study is to figure out what mechanisms underlie this range of differences and try to identify strategies being used by the kids who are picking up and generalizing a lot of vocabulary,” explains Nadig. A better understanding of these processes could help guide future therapies for language development in children with autism.

According to Nadig, this study could have important clinical implications by providing insights into possible ways to help children with autism spectrum disorders communicate more effectively. For example, it might confirm that subtle things parents can do when interacting with their child — such as following their child’s focus of attention and using multiple cues when labeling an object — may help facilitate language development, explains Nadig.

The study will also provide groundbreaking data from Francophone children with autism. “To date, all careful research on processes of language development in autism has been done in English, so we’re going to be adding substantially to the literature by doing the parallel study in Québecois French,” explains Nadig.

The target enrollment for the study is 80 children. This includes 20 Anglophone children with autism spectrum disorder who are two to six years old at enrollment and who are matched for language skills with 20 typically-developing Anglophone children who are 15 months to two years old at enrollment.

In parallel, the study is enrolling two similar groups of Francophone children. Recruitment of Anglophone children has been completed and many of the children will be finishing the study this spring, with the Francophone study well underway.

The typically-developing children were drawn from the McGill Infant Recruitment Group (MIRG) research database. The children with autism spectrum disorders were recruited primarily from the Autism Spectrum Disorders Program at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

Parent and child study participants make three visits to the McGill Language Aquisition lab, located in the Stewart Biological Sciences building: an initial, one-and-a-half-hour visit, a 30-minute visit six months later, and a third visit a year after the initial visit. At the beginning and end of the study the children take part in a standardized test that measures their language skills, and the parents fill out a questionnaire about their child’s vocabulary, providing a measure of language growth over the year. Children also take part in a range of experimental tasks, and impromptu play is part of the sessions.

Preliminary findings from three parts of the six-part study have been accepted as posters for the IMFAR (International Meeting for Autism Research) meeting in San Diego, in May. One poster examines child-directed speech or “motherese” and its relationship to greater vocabulary gains. A second poster, based on parent-child interactions during free play, suggests that children with autism spectrum disorders use less “pretend” play and their parents are more likely to redirect the child’s attention. A third poster suggests that children with autism who have higher language abilities are able to learn words by following social cues.

The fourth part of the study looks at how children generalize new words to other objects in the same category. The fifth part investigates what cues parents naturally use to label objects for their children in a play setting. The sixth part examines how statistical properties of parental speech are related to the child’s vocabulary. After the final data from all parts of this study has been obtained and analyzed, the group will submit manuscripts to medical journals.

“A study of this nature involves the ongoing dedication of members of my whole team, who have been essential to its conduct,” Nadig emphasizes. In addition to leading her research team, she teaches courses for graduate students in speech pathology, including one on autism spectrum disorders.

This combination of research and teaching is what drew Nadig to McGill, and it builds on her earlier training. She studied developmental pragmatics in the normal population and obtained a PhD in cognitive science from Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island. From that work, she became interested in autism, which led to doing an intensive post-doc at the UC Davis MIND (University of California, Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders) Institute, where she trained with psychologists who are experts in autism. Part of her work included a project to see if autism could be detected at 12 months based on a child’s lack of response when called by his or her name.

“McGill’s Communication Sciences and Disorders program is the most research-focused of anywhere that I know,” says Nadig, adding that “given my two aspects of training, this is a perfect fit because I’m able to keep doing basic science research, and teach future practitioners.”