New study sheds light on cellular processes that may lead to allergic immune responses

Allergic diseases are widespread, affecting an estimated 30-40% of people around the globe according to the World Allergy Organization. Asthma Canada, for example, notes that allergic asthma has become the number one chronic illness in children in Canada, and is a major cause of their hospitalization. The incidence of allergic disease has been rising for years in industrialized countries, for reasons that are not yet fully understood. A new study from researchers at McGill University, published in Nature Immunology, hopes to shed some light on this question.

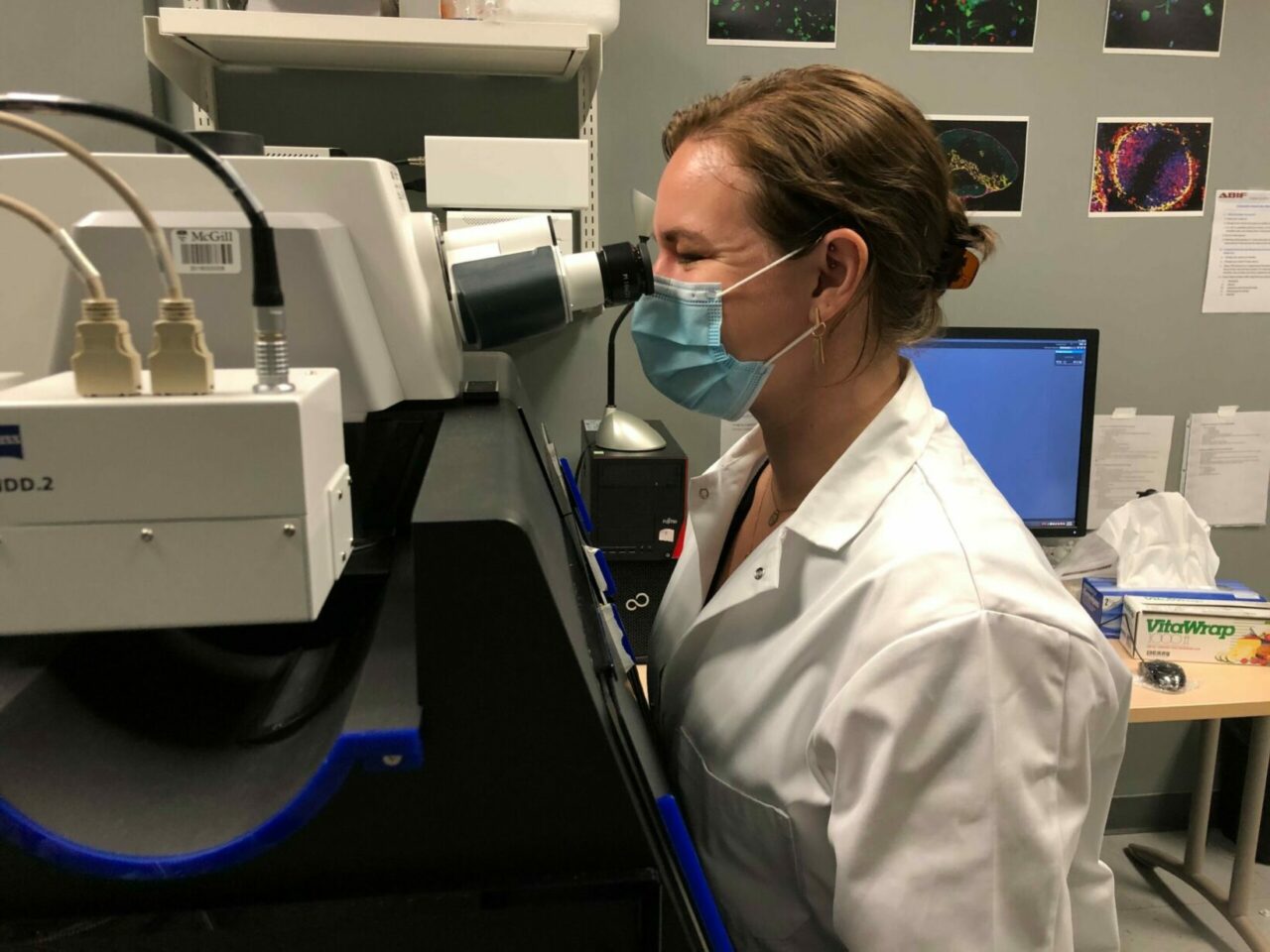

The leading theory to explain the rise in allergies, known as “The Hygiene Hypothesis,” posits that the way of living in industrialized countries has become ‘cleaner’ through the regular use of antibiotics and disinfectants, causing people to be less exposed to environmental microorganisms that would normally train our immune system to be more tolerant. “There is mounting evidence that decreased exposure to infectious diseases and reduced microbiome diversity in early life, has inadvertently lead to changes in immune cell development and the loss of immunoregulatory mechanisms such that when we encounter allergens, our immune system mounts an inappropriate allergic response,” explains Dr. Judith Mandl, Assistant Professor in the Department of Physiology at McGill and the study’s senior author.

“Our work leads us to speculate that, in addition to this decreased tolerization to harmless microbes, it is possible that we are also exposed to substances in our environment that induce cell damage and death – for example, surfactants in detergent, which are harmful to barrier surfaces such as the intestines and lungs. This may additionally prime our immune system to generate allergic, type-2 responses. Currently we mostly treat the symptoms of allergy rather than cure its underlying cause. Understanding the signals that lead to allergic, type-2 T cell responses is critical to enable us to develop and employ preventative or curative treatments.”

Putting the clues together

Parasitic worms, toxic substances, snake venoms, and allergens may not appear to have much in common, but they actually share one important feature: the type of immune response that they elicit. These very diverse stimuli all result in what is known as type-2 immunity, which is molded by CD4+ T cells called Th2 cells. The molecules that Th2 cells release leads, either directly or by the recruitment of additional immune cells, to vasodilation, smooth muscle peristalsis and increased mucus production, all of which elicit expulsion mechanisms at barrier surfaces. “The signals that drive CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th2 cells remain incompletely understood,” notes Caitlin Schneider, a PhD student supervised by Dr. Mandl and the study’s first author. “To elucidate the underpinnings of type-2 immunity, we studied a particular situation where the immune response ‘goes wrong’: a heritable defect which leads to a greater incidence of allergic responses.”

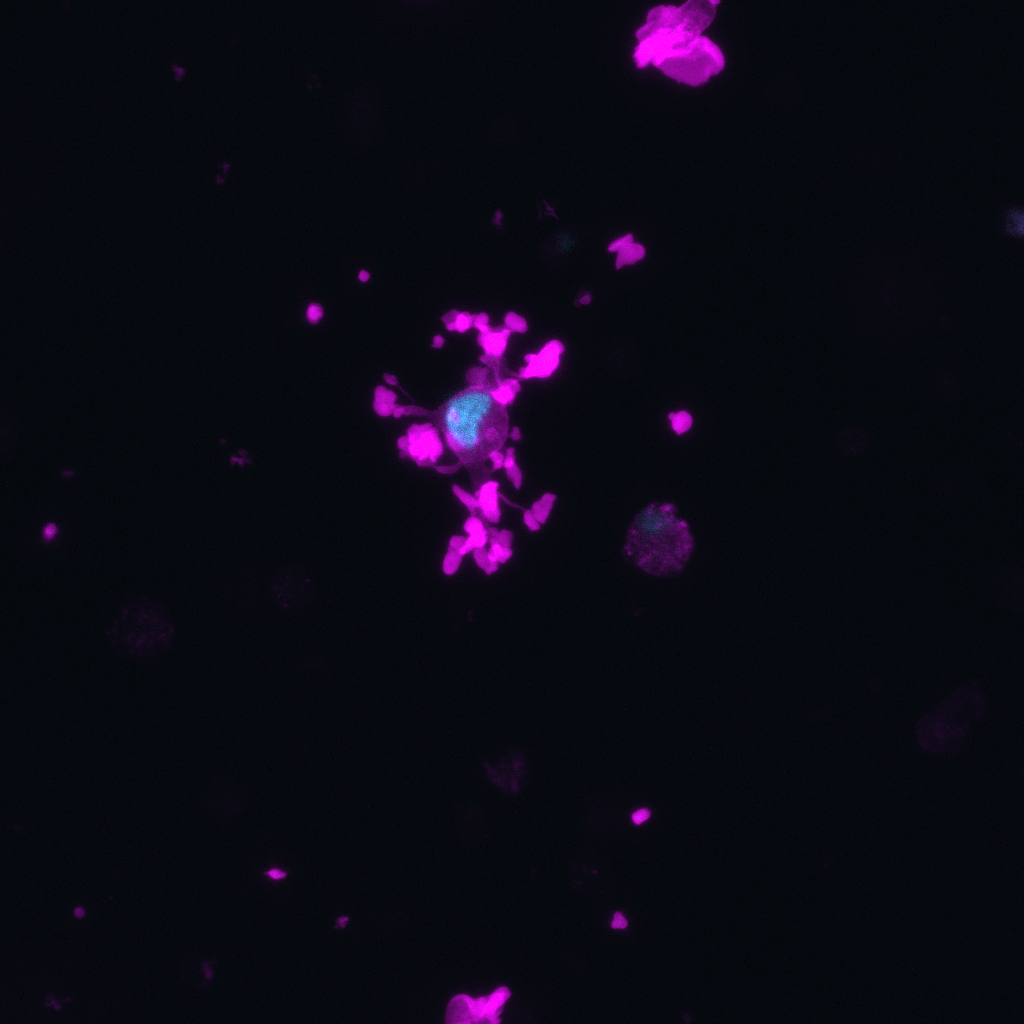

The researchers found that this heritable defect is caused by loss-of-function mutations of the gene DOCK8 which leads to immunodeficiency, but also, paradoxically, Th2-driven allergic diseases. Using a mouse model of Dock8-deficiency they interrogated the signals that lead to Th2 differentiation in this context. “Our work identifies cell death as a key driving factor in the type-2 response,” says Caitlin. “Previous work has demonstrated the importance of DOCK8 in immune cell migration. Here we found that Dock8-deficient mononuclear phagocytes, a cell type of the innate immune system, are exquisitely sensitive to migration-induced shattering (cytothripsis) when they traverse tissue, such as the lung, and that their death is ultimately what induces the Th2 skew in Dock8-deficiency. Strikingly, we found that even in wild-type mice, introducing dying cells during infection was enough to induce a Th2 bias. Our work has taught us that cell death can be read out by the immune system as a signal that a type-2 immune response should be mounted, indicating that cell death may play a role in allergic responses more broadly.”

The researchers note that they have not yet fully defined the specific signals associated with cell death that lead to allergic responses, although they implicated IL-1beta as a necessary but not sufficient signal. Additionally, because there are many ways that cells can die, it is not clear yet which types of cell death might be read-out by the immune system as a prompt for a type-2 response.

“We hope to identify the particular type of cell death that can induce a type-2 immune response and the exact signal or signals released by dying cells that are necessary,” says Dr. Mandl. “We are also further investigating the role that Dock8 plays in the healthy migration of immune cells, learning more about differences between immune cell types and their migration within different tissues in the process.”

“Migration-induced cell shattering due to DOCK8 deficiency causes a type 2–biased helper T cell response”, by C. Schneider, J. Mandl, et al, was published in Nature Immunology on October 5, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41590-020-0795-1.

October 6, 2020