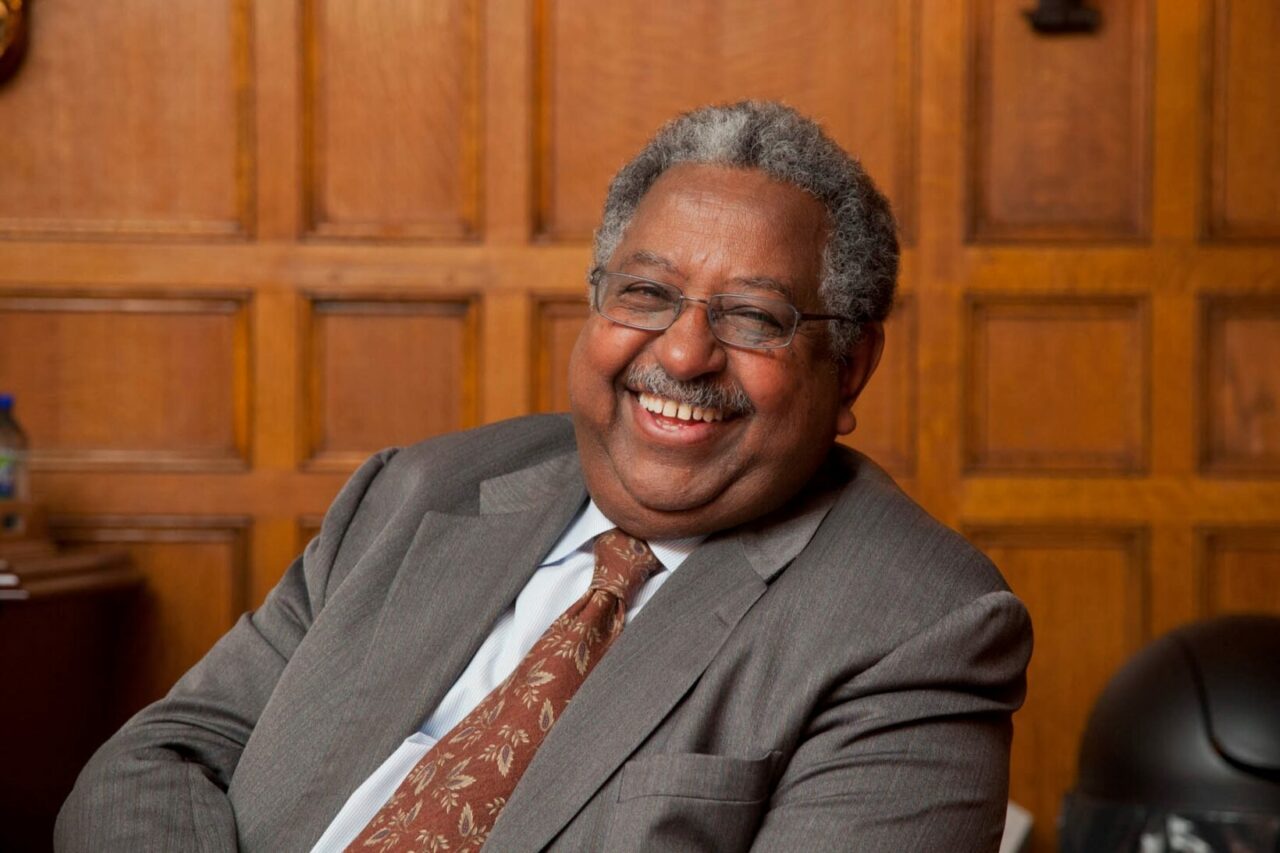

McGill is fortunate to count Dr. Haile T. Debas (MDCM ’63) among its alumni. When it came time to select a medical school, the native of the African nation of Eritrea had his pick from among hundreds of institutions.

McGill is fortunate to count Dr. Haile T. Debas (MDCM ’63) among its alumni. When it came time to select a medical school, the native of the African nation of Eritrea had his pick from among hundreds of institutions.

“I had a choice [in the end] between Edinburgh, Harvard and McGill,” recalls Debas, who was accepted at all three. He was attracted to McGill because it was international and he thought it would have the advantages of both the American and British systems. When Harvard asked that he complete a qualifying year in English, it further cemented his decision to head to Montreal.

“I absolutely made the right choice,” says the proud alumnus today. “Montreal is a wonderful place to be a student. And McGill was caring. Not too many institutions go to the trouble to make sure that each student is doing ok – it takes a lot of effort. To me it was mind-boggling. We also had wonderful teachers – characters – like C.P. Leblond and C.P. Martin. There were individuals that you would always remember. I had a great time [at McGill].”

In the 50 years since earning his medical degree, Debas has built his legacy as a pioneer in global health. “In an interrelated, rapidly dwindling world, the problems they have over there [in other parts of the world] are also our problems,” says the former Chancellor and Dean of the School of Medicine at the University of California at San Ffrancisco (UCSF).

Among many accomplishments, Debas cites starting the global health programs at UCSF and at the ten campuses of the University of California as being one of the things for which he is most proud. This consortium of universities for global health now includes 130 universities in both North America and the developing world.

While we often equate global health with philanthropic and humanitarian efforts of aid, to truly have an impact we must go far beyond that not only for the benefit of others but in our own self-interest.

“I’ll give you two important examples,” says Debas. “[First] remember when SARS arrived in Toronto at the speed of the jetliner that brought the people? Secondly, you see tuberculosis (TB) in California. We had almost abolished TB in the 70s and 80s, but now there is a recurrence and what’s worse is that it is now multiple drug resistance TB. Why is that happening? Because the drug resistance develops in the developing countries – there are fake drugs, patients don’t take the drugs appropriately, they get a prescription and want to save it and extend it for a month instead of taking it for two weeks. All of this gives the bacteria the chance to develop resistance. You can’t fight that here. You have to fight it there.”

Globalization provides not only an opportunity for multiplying wealth but also an opportunity for the rapid sharing of problems, like SARS. It’s no longer possible for a developed nation to be an island on its own.

While billions of dollars in aid have been sent to Africa, Debas says that until recently this money has accomplished very little. The reason for the change, he explains, is that now we have developing economies that are creating wealth and a middle class rather than just handouts. There are 17 countries in Africa today where the annual growth is 6-10 per cent.

This applies to global health as well, where the model can no longer be about just going in somewhere, doing something and getting out. “There was a story in an English newspaper a few years ago about a child in Tanzania who was hit by a car,” tells Debas to illustrate his point. “Another car came and took the child to a hospital that was 15-20 kilometres away. That hospital had received a lot of funding and had a lot of equipment. They arrived and nobody knew how to use the equipment – they couldn’t even provide oxygen even though they had the cylinders!”

“You have to leave something lasting and the best way to do that is by training the workforce,” says Debas. “By that I mean not just the doctors, the nurses, the technicians but also the managers. The biggest deficiency in African countries is management at the departmental level, at the school level, at the university level at the ministry level. Certain things you take for granted as a Canadian don’t happen there. If we could help to build the human capacity that would be great.” This is the vision that Haile Debas sees for global health and what is required from current and future generations of health care practitioners. The ultimate success of these efforts, he says, can only be seen 10-20 years down the road.

March 18, 2014